💥 Read this must-read post from Culture | The Guardian 📖

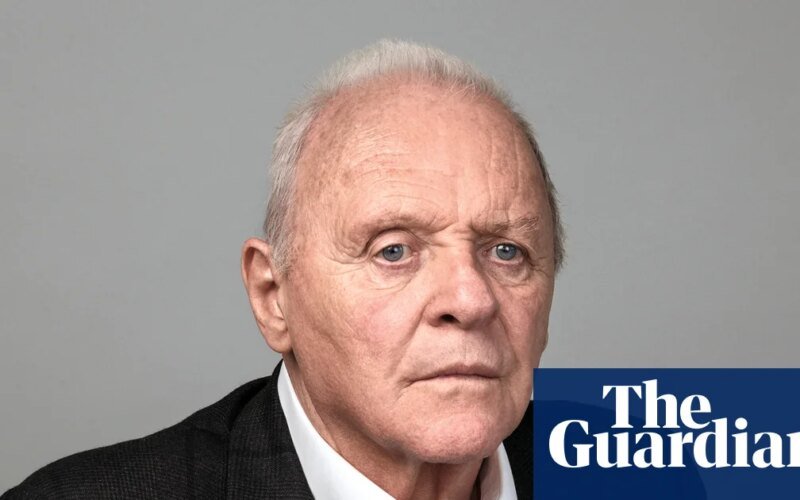

📂 Category: Autobiography and memoir,Anthony Hopkins,Books,Culture,Celebrity,Film,Stage,Biography books

✅ Main takeaway:

It’s the greatest entry in the history of cinema, and it doesn’t move a beat.

FBI rookie Clarice Starling must walk along the row of cells until she reaches Dr. Lecter’s reinforced glass tank, where the man himself simply stands, his face a living skull of demonic malevolence, frighteningly immobile in his form-fitting blue prison jumpsuit—unable to move, that is, until such time as he throws himself against the glass, making an extraordinary hissing sound. Since then, a billion true crime documentaries have revealed that real serial killers are boring as hell, and there’s nothing like Anthony Hopkins’ on-screen presence.

He was completely unknown when he landed that Oscar-winning role in 1989’s The Silence of the Lambs: a star wasn’t born, he was a superstar, a legend. Hopkins happily recalls in this new biography that his Doctor Lecter was based on Bela Lugosi’s Dracula, on Stalin as his daughter remembers him, and on his stern-eyed Rada mentor Christopher Fitts. There was a father-daughter dimension in these scenes as well; It is a painful subject for Hopkins, who also describes how Lear was subconsciously affected by agonizing guilt towards Abigail, the estranged daughter from his disastrous first marriage in 1966 to Petronella Parker, who resented his absence and drinking.

The title is taken from an old wartime photo of Hopkins as a young child on the beach with his father – a child who probably thought he would never be well. He was a bewildered, lonely, vulnerable young boy from Port Talbot, the son of Richard Arthur Hopkins, the scene-stealing supporting player here: a baker and a man’s man, a plain talker who abhorred Bible-punching church hypocrites and did not believe in displaying his feelings, but who had a tinge of sad, tearful romanticism. It was Hopkins Sr. who most resented the way they had to deal with wealthy relatives like Aunt Patty, whose husband knew Bevan’s flute and could get young Anthony into a fancy school: “Because they’re so rich!” He’s raving in the car on the way there. “We’re all hoping to get some choices! Bloody bullshit, that’s what it is!”

The groveling paid off for a while. Hopkins was a hopeless student at his new school. But one day, in an English class, he had to read John Masefield’s poem “The West Wind” – which cannot be seen – and this sound came to life; The teacher and the other boys were astonished. He says plausibly that it was poetry alone that set him free. That, and joining the YMCA Drama Club. Remarkably, he left school hopelessly, took up acting, and to his parents’ surprise was on stage with Laurence Olivier at the Old Vic within 10 years. He did it almost on his own, although in those days there were scholarships to go to the Rada – a path of upward mobility for representatives of the working class. His father remained in awe of Antony’s global success: when he asked his son to read Yorick’s speech from Hamlet, Hopkins Sr. listened intently and then went into another room and burst into tears.

As for the irascible and bloody-minded son, he left the National Theater company in a fit of resentment – to Olivier’s profound dismay and disapproval – but he lucked into a breakthrough TV role as a suspected war criminal in Leon Uris’s QB VII, which indirectly led to parts such as those in David Lynch’s The Elephant Man and a star-studded career on screen, which he preferred to the stage. An alcoholic, he quit in 1975 and survived into middle age to give great performances, including Lecter, the servant Stevens in The Remains of the Day with Emma Thompson, and the senile old man in The Father – his second Oscar.

In the latter half of the book, his character becomes more mysterious and more studied. Some stories don’t quite come to fruition. He remembers being taken to lunch by his co-star in Oliver Stone’s film Nixon, the well-respected actor Paul Sorvino, who wanted to tell him about his performance because Nixon had not been successful. Was this the right moment for Hopkins to learn something from the legendary star of Scorsese’s Goodfellas? Not exactly. Hopkins seems to go along with Stone’s dismissal of Sorvino as motivated by jealousy. truly?

He repeatedly plays the tough, humble professional actor who believes it’s your job to get there on time, know all the crew names and get on with the job. Totally so. But he also recounts confronting an obnoxious director who had given the young man an extra shout: “Apologize to her! And learn some manners. If you do that again in front of me, I’ll change your face!” Hopkins sounds like someone who has given up drinking, but perhaps not the hostility that came with it. A Shakespearean like him must know Cornwall’s lines about Kent from Lear: “He cannot flatter, he! A mind true and clear—that must tell the truth!”

After promoting the newsletter

Hopkins concludes his book with a long appendix consisting simply of his favorite poems: This may be an outrageous indulgence, and yet it is to the transcendent power of these works, and the system of learning them by heart, that they owe their success.

Share your opinion below! Share your opinion below!

#️⃣ #Alright #Kid #Memoir #Review #Anthony #Hopkins #Legend #Good #Mood #Biography #memoirs