✨ Check out this must-read post from BBC Culture 📖

📂 Category:

✅ Key idea:

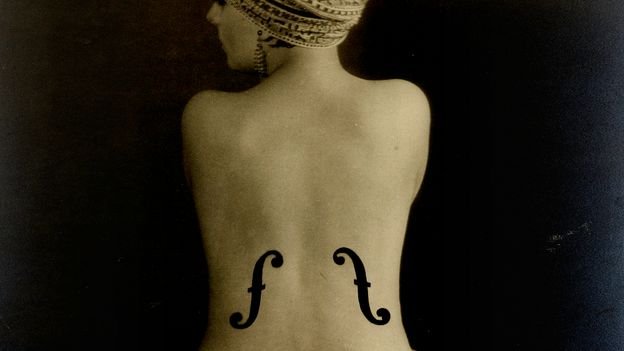

In Ingres’s novel La Grande Odalisque, 1814, the absurdly elongated lumbar part of a relaxed woman was derided by critics for its anatomical illogicality. The artist Tavy had his subject’s spine so severely stretched, that medical scientists have since estimated that she was given at least five extra vertebrae—a deformity that would, in fact, lead to profound physical paralysis. Rather than enhancing sexuality, these interventions distort the bodies of their subjects. In Man Ray’s picture, the placement of the holes theoretically impairs Kiki’s ability to sound. They silence her.

“Teasing mantra of love and control”

And it doesn’t stop there. These flaws are also signs of enslavement. By the time Man Ray created his work in 1924, holes in the air were largely in place. Once mainly associated with elite orchestral instruments, its meaning began to broaden. Modern mandolins were already equipped with f-holes, and a year before Man Ray made Le Violon d’Ingres, Gibson released the L-5 arched guitar, the first mass-market instrument of its kind to use an f-hole, giving the instrument the volume and resonance needed for performance in dance halls and jazz clubs. Suddenly, f-slots were no longer just shorthand for width and power, but were symbols of commodity culture and mass-produced sound. Kiki was tattooed on her back, marking her and turning her into something to be bought and sold.

But paradoxically, it also deepens the meaning of the image, enriching the scope of its cultural resonance. The violin has long carried occult overtones in art, music and literature – from Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s “Triumph of Death”, 1562, in which Death plays the violin, to Niccolò Paganini’s unreal violin-playing virtuosity, which sparked rumors of a Faustian pact. The relationship between the violin and the world we cannot see was well known to Man Ray’s contemporaries. A decade before Le Violon d’Ingres, Marcel Proust likened the experience of hearing a violin “to listening to a captive genie, struggling in the dark… like a pure, supernatural being revealing its invisible message over time.” By combining the form of the kiki with that of the violin, Man Ray taps into an interesting tradition of grasping the incomprehensible.

More like this:

• The turbulent history of the Union Jack

• The pioneering photographer who captured the horror of World War II

• 12 of the most notable images of 2025 so far

In Man Ray’s imagination, images like Le Violin d’Ingres were created as talismans that could conjure invisible spirits. The so-called “radiography” technique to which the Metropolitan Gallery was devoted—conceived by the artist as an immaterial spin on physical X-rays—was highly ritualistic. To create them, the artist sought to avoid the soulless mechanism of the camera by placing objects directly on light-sensitive paper, a process he believed could access hidden energies and dimensions beyond human perception.

⚡ What do you think?

#️⃣ #Man #Rays #famous #nude #Violon #dIngres #meets #eye