💥 Check out this must-read post from Culture | The Guardian 📖

📂 Category: Horror films,Film,Culture,Hereditary,Sinners,Midsommar,M3gan,The Babadook,The Blair Witch Project,Get Out,The Witch

💡 Main takeaway:

Every week at your local movie theater, there’s a new horror movie. If a movie isn’t a reboot (I Know What You Did Last Summer) or a sequel (Final Destination Strains), it’s a prequel (The First Omen; A Quiet Place: Day One), the return of a beloved gothic icon (Luc Besson’s Dracula: A Love Story; Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein), or a horror movie (Dangerous Animals) in which the psycho killer’s weapon of choice is not. Blades, but sharks. Or it’s a deliriously exciting and inventive treatise from one of the new wave of horror auteurs shaking up the cinematic zeitgeist: say, Ryan Coogler’s Sinners, or Zack Krieger’s Weapons.

Playing with metaphor, imagery, and narrative, horror always deals with difficult truths about death, decay, and the human condition that mainstream productions tend to shy away from as disgusting, embarrassing, or painful. In an age when thrillers, romantic comedies, and action films don’t want to rock the boat for fear of upsetting risk-averse studios and streaming services, horror films are uniquely equipped to address the hot-button issues of our time: immigration (his home); Mental health (Smile 2); Toxic Masculinity (Invisible Man); Artificial Intelligence (M3gan); sects (mid-summer); fanaticism (heretic); gender dysphoria (I saw the TV glow); Conspiracy theories (broadcast signal hacking); Zoom Meetings (Host); epidemics (sadness); environment (in the land); Politics (purification); Dementia (residual); Pregnancy, motherhood (Huesera: The Bone Woman; Mother’s Baby) and – always a popular theme in the horror world – bereavement (The Babadook; Hereditary; Talk to Me; Bring Her Back etc.).

In an age of polarization, institutional collapse, climate anxiety, and the collapse of shared reality, horror has emerged as the genre best able to address our fractured moment. Once decried by respected film critics as only a short step forward from pornography, horror today is no longer just of the moment; It reveals itself as the defining genre of the 21st century.

The last great boom for horror films was during the 1970s, when George Romero, Tobe Hooper, John Carpenter, and Wes Craven dragged the horror genre, kicking and screaming, out of its gothic past and into the world of rural America, strip malls, and suburbs, in subversive films that reflected widespread social anxiety and distrust of authority in the era of Vietnam, Watergate, and disillusionment. Counterculture. But horror moves in cycles, from innovation to exploration to recycling and parody, and by the 1990s, movies had bogged down in parodies (Scary Movie), duff remakes (The Haunting), and reckless directors who imagined they were exploiting subtexts no one had ever explored (Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Mary’s Frankenstein Shelley, Wolf).

And then, just in time for the millennium, an unholy trilogy of songs revived the dying pulse of the genre to send it into the next century. The Blair Witch Project showed that an entire branch of filmmaking could be revolutionized on a very low budget, by cleverly using the Internet as a marketing tool and replacing the primal fear of getting lost in the woods with expensive special effects. It wasn’t the first horror film to use found footage, but it was instrumental in turning this into one of the most cost-effective tricks in low-budget filmmaking.

Besides Blair Witch, two other films signaled the revival of an almost forgotten subgenre – the ghost story, reworked for the modern age and a media-savvy audience. Director M. Night Shyamalan’s The Sixth Sense created a devastating twist on the alternate reality scenario that would underpin much of horror and sci-fi in the new century. The cursed VHS tape of the J-horror Ring phenomenon was a harbinger of the use of new technology that would permeate the genre through chilling cycles on social media, influencers, artificial intelligence, and the dark web.

After Ring, the increasing availability of DVD and broadband penetration made non-Anglophone horror cinema, especially from France, Japan, and South Korea, more accessible to horror fans in the West, permanently changing what “American” or “Western” horror meant so that directors like Jordan Peele and Ari Aster later consciously drew from this international lexicon. The New French Extremism (exemplified by Irreversible, in which a man mashes his face into pulp with repeated blows from a fire extinguisher, or Martyrs, in which a woman is skinned to death) pushed the framework of what was acceptable on screen. The subgenre eventually dubbed “torture porn” (Hostel; The Human Centipede (first sequence); And You Really Don’t Want to Know What Happens in a Serbian Movie) raised over-the-top content for a few years before giving way to less grim, more viewer-friendly ghosts, curses, and bogeymen. The influence of torture porn continues to this day in hardcore films like Terrifier 3, which grossed 45 times its $2 million budget, so there’s clearly still a market for uninhibited sadism as practiced by killer clowns. The box office success of Terrifier 3, along with director Robert Eggers’ more classy-leaning Nosferatu, underscores the genre’s new ecosystem, where elevated horror and exploitation play in and out of each other.

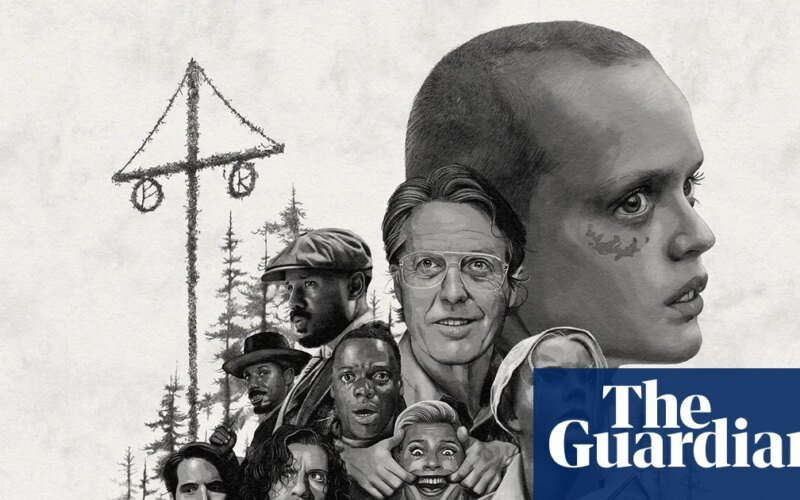

While the Blair Witch/Ring wave proved that horror could be profitable and innovative, the current wave’s inflection point reached with The Witch (2015), before being solidified by Get Out (2017) and Hereditary (2018). This moment succeeded where previous innovations had failed because it coincided with rising rates of Internet-fueled alienation and a new understanding of trauma, including cultural and generational trauma, which horror was uniquely positioned to address. At the same time, a new wave of horror auteurs is helping to bring the horror genre out of exploitation circles and midnight movies and into the art world. The likes of Jordan Peele (Get Out), Jennifer Kent (The Babadook), and Eggers (Nosferatu) seem to regard horror not as a different genre, but rather an integral part of their creative toolkit. They have abandoned the traditional 90-minute running time in favor of an epic length often associated with blockbuster releases, giving themselves room to explore themes and develop characters more fully.

“La Belle” (130 minutes) is not just a horror film, it is a neo-Western sci-fi horror film. Kent’s The Nightingale (136 minutes) is a rape-revenge horror drama that also deals with colonialism. Midsommar, directed by Ari Aster (147 minutes), is a folk horror film about bereavement, trauma, and broken relationships. Coogler’s Sinners (137 minutes) is a deep Southern gothic period action drama, with vampires. (The fact that some mainstream critics have been unable to get on board with the idea of Coogler bringing vampires into the mix suggests that old anti-horror prejudices die hard.)

New horror writers know the history of the genre, and use their knowledge to add unusual twists and turn audience expectations on their head. Besides extended runtimes, directors like Krieger, Bale, and Aster pioneered the formal innovations that characterize high horror on an artistic level: disorienting or unnatural color palettes; Compositions that deprive the viewer of safe framing; Even more extreme is their deployment of extended periods of silence and narrative ambiguity to induce unease or dread in audiences rather than shake them with a sustained barrage of terror. Cregger’s Barbarian, about an Airbnb stay that goes horribly wrong, clocks in at a relatively brisk 102 minutes, but its unconventional structure is very 21st-century, as are the director’s clever casting choices, which heighten the tension. Its follow-up, Arms (128 minutes) distills the details of its central mystery – 17 missing children – across separate points of view that eventually converge in a perfectly tight climax that embraces both humor and horror, but without turning the film into a horror comedy.

Films by new horror auteurs are taken more seriously by critics, who sometimes use the term “elevated horror” to distinguish them from the cheap and cheerful films of the past. This shift became official when the Sundance, Cannes, and Toronto Film Festivals began programming horror films in their main competitions—a shift made possible by a generational change in film criticism, with younger critics who had grown up appreciating horror as a legitimate art removed from older gatekeepers. But horror also helps blur the boundaries between art and the mainstream. Horror films’ unique economic model — low budgets that can reap astronomical profits — gives auteurs a creative freedom that big-budget filmmakers can only dream of, and explains why broadcasters and studios, sensitive to risk, are willing to gamble on officially daring horror projects they’d never greenlight in other genres. Production and distribution company Blumhouse Productions has produced such Oscar-nominated dramas as Whiplash and BlacKkKlansman, but made its name with the successful Paranormal Activity franchise, leading Peele’s Get Out to a critical and commercial success that sparked a wave of media discourse about a post-America. Racism, and the potential for non-white or female filmmakers to bring new perspectives to a genre that had previously been almost universal. Supervised exclusively by white men.

The name of another distribution company, A24, has become so synonymous with elevated horror that fans and critics take notice when they see it attached to new projects, whether it’s the award-winning work of Liorgos Lanthimos, Joanna Hogg and Sean Baker, or the latest film from Australian duo Danny and Michael Filippo, whose supernatural thriller Talk to Me was a huge hit a few years ago. Their latest follow-up, Bring Her Back, is built around Sally Hawkins’ performance so terrifying, you’ll never be able to watch Paddington again without shuddering.

And on another well-known distributor’s slate, Neon, Bong Joon Ho’s Oscar-winning Parasite and Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire, take on Sidney Sweeney’s Trauma Immaculate (a metaphor for forced birth if ever there was one), a rape-revenge fantasy from director Coralie Farget, which will continue to thrill audiences around the world. Globe with Demi Moore smash The Substance, directed by Brandon Cronenberg, whose Possessor and Infinity Pool explore the body horror genre pioneered by his father David in the 1970s.

Within six months, Neon had a mix of successes from another filmmaker with horror in his genes: Osgood Perkins, son of Anthony Perkins, who played Norman Bates in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho. Longlegs was an FBI procedural nightmare starring Nicolas Cage as a grotesque, mysterious serial killer. Neon borrowed its marketing tactics from The Blair Witch Project, ditching expensive TV ads in favor of cryptic Internet clips and billboards displaying phone numbers connected to pre-recorded messages from the film’s killer. Perkins followed it up with the ragtag comedy The Monkey, adapted from a Stephen King story. “Everyone dies,” says one of the distressed characters. “Some of us are at peace and asleep, some of us are in a terrible state. And that’s life.”

And in today’s world, real life is scarier and more depressing than anything a filmmaker could ever dream of. In the traditional Hollywood model, corruption is exposed through the righteous media, and the President of the United States (as played by Viola Davis or John Cena in recent action movies) is firmly on the side of good against evil, but that approach won’t cut it anymore. Horror is perhaps the only genre that faces the challenges and fears of the ever-evolving present with its eyes wide open. If we’re truly living at the end of time, then we’ve got you covered, creating a space where our collective fears are unleashed and allowed to run free – safely contained by screen edges and limited runtime.

{💬|⚡|🔥} {What do you think?|Share your opinion below!|Tell us your thoughts in comments!}

#️⃣ #Shock #therapy #scary #movies #making #money #Horror #movies