💥 Explore this awesome post from Hacker News 📖

📂 Category:

📌 Main takeaway:

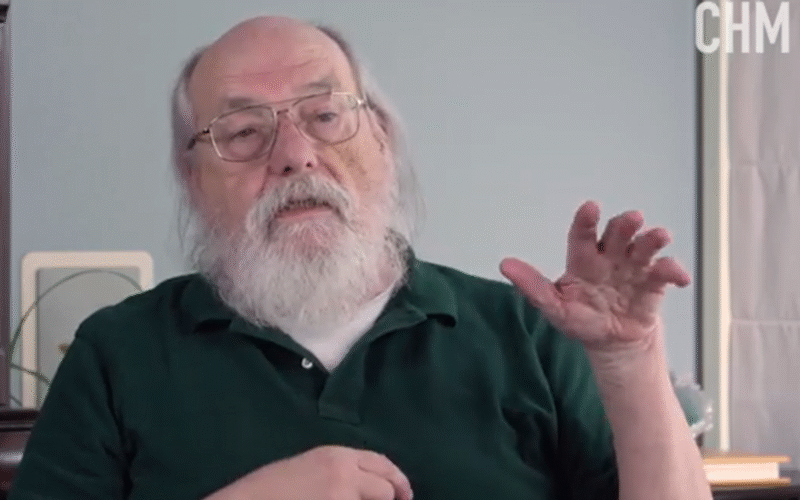

The 82-year-old Ken Thompson has some amazing memories about the earliest days of the Unix operating system — and the rowdy room full of geeks who built it.

This month Silicon Valley’s Computer History Museum released a special four-and-a-half-hour oral history, in partnership with the Association for Computing Machinery, recorded 18 months ago by technology historian David C. Brock. And Thompson dutifully recalled many of his career highlights — from his work on the C programming language and Unix to the “Plan 9 from Bell Labs” operating system and the Go programming language.

But what comes through is his gratefulness for the people he’d worked with, and the opportunity they’d had to all experiment together in an open environment to explore the limits of new and emerging technologies. It’s a tale of curiosity, a playful sense of serendipity and the enduring value of a community.

And along the way, Thompson also tells the story of raising a baby alligator that a friend sent to his office at Bell Labs. (“It just showed up in the mail… They’re not the sweetest of pets.”)

The Accidental Birth of Unix

Travel back in time to 1966, when 23-year-old Thompson’s first project at Bell Labs was the ill-fated Multics, a collaboration with MIT and General Electric which Thompson remembers as “horrible… big and slow and ugly and very expensive,” requiring a giant specially-built computer just to run and “just destined to be dead before it started.”

But when the Multics project died, “the computer became completely available — this one-of-a-kind monster computer… and so I took advantage.”

Thompson had wanted to work with CRAM, a data storage device with a high-speed drum memory, but like disk storage of the time, it was slow to read from memory.

A magnetic “drum memory” data storage device

Thompson thought he’d improve the situation with simultaneous (and overlapping) memory reads, but of course this required programs for testing, plus a way to load and run them.

“And suddenly, without knowing it — I mean, this is sneaking up on me…. Suddenly it’s an operating system!” Thompson’s initial memory-reading work became “the disk part” for Unix’s filesystem. He still needed a text editor and a user-switching multiplexing layer (plus a compiler and an assembler for programs), but it already had a filesystem, a disk driver and I/O peripherals.

Thompson wondered if it took so long to recognize its potential because he’d been specifically told not to work on operating systems. Multics “was a bad experience” for Bell Labs, he’d been told. “We spent a ton of money on it, and we got nothing out of it!”

“I actually got reprimands saying, ‘Don’t work on operating systems. Bell Labs is out of operating systems!”

One-Digit User IDs

But now Unix had its first user community — future legends like Dennis Ritchie, Doug McIlroy, Robert Morris and occasionally Brian Kernighan. (“All the user IDs were one digit. That definitely put a limit on it.”) Thompson remembers designing the Unix filesystem on a blackboard in an office with Rudd Canaday — using a special Bell Labs phone number that took dictation and delivered a typed-up transcript the next day. And Joe Ossanna “got things done” with a special talent for navigating Bell Labs’ bureaucracy that ultimately procured a crucial PDP-11 for the Unix team to work on.

“We were being told no, ‘because we don’t deal in operating systems.’” But Ossanna knew the patent department was evaluating a third-party system for preparing documents — and Ossanna proposed an in-house alternative. “So we got our first PDP-11 to do word processing.”

Ken Thompson (sitting) and Dennis Ritchie at PDP-11

And history shows that it happened partly because the department paying for it “had extra money, and if they didn’t spend it, they’d lose it the next year…”

So the young Unix community picked up somewhere between five and eight new users, Thompson remembers, “the secretaries for the Patent Department, writing patents on our system!”

The Fellowship of the Unix Room

That PDP-11 wound up in “a spot on the sixth floor where we cleaned out a vending machine and a couple of cages of stored junk from 1920,” Thompson remembered. They eventually installed a second PDP-11, which turned the room into “a hotbed of things,” with discussions about networking — and an upcoming typesetter for documents. Thompson calls it the Unix room, and most of them eventually had extensions for their phones wired into the room. (It even had its own call-switching PBX …)

There was camaraderie and some laughter. He adds later, almost as an aside, that “in the Unix room, we used to pick locks a lot and steal things.” (When one of the secretaries discovered security had affixed a “parking boot” to her car that was parked in the wrong zone, “we went down there, and we picked the lock and stole the boot. And after that, slowly, we picked up all four boots, and we hid them under the raised floor of the Unix room…”)

The punchline? “The head of security came around and pleaded with us. ‘We won’t pick on your secretaries if you give us back our boots.’”

And the deal was accepted.

Dennis Ritchie (left) later said their motivation was to build a system “around which a fellowship could form,” but Thompson says that’s more of a description of what transpired than an actual design goal.

Thompson remembers things like gathering for a regular “Unix lunch” in the Bell Labs lunchroom, which “caused a symbiosis of thought and things. It was great.” Although it always seemed to happen just minutes after the lunchroom stopped serving food. “If I was late, I’d buy McDonald’s and sit down at the lunchroom with my McDonald’s. They used to get mad at me for that …”

Growing From Community

Looking back, Thompson credited the success of C and Unix to Bell Labs and its no-pressure/no users environment. “It was essentially a ‘whatever you want to do’ atmosphere, and ‘for anybody you wanted to do it for’… Bell Labs was by far the biggest contributor to this whole type of programming.”

Bell Labs was an eclectic mix, but this community paid unexpected dividends. While Lee McMahon was originally hired as a linguistics researcher, he was ultimately the one who procured machine-readable dictionaries for the Unix team, along with machine-readable version of the Federalist Papers. (When the whole text wouldn’t fit into their text editor ed, Thompson famously created the line-by-line pattern-scanning tool grep.)

And in the end Thompson says Unix grew from there for one simple fact: People liked it. It spread within Bell Labs, at first for “the administrative kind of stuff, typing in trouble tickets…” But this being a phone company, “then it started actually doing some switching, and stuff like that. It was getting deeper and deeper into the guts of the Bell System and becoming very popular.”

Open Before Open Source

Thompson credits Richard Stallman with developing much more of the open source philosophy. “But Unix had a bit of that.” Maybe it grew out of what Dennis Ritchie was remembering, that fellowship that formed around Unix. “For some reason, and I think it’s just because of me and Dennis, everything was open…”

It was just the way they operated. “We had protection on files — if you didn’t want somebody to read it, you could set some bits and then nobody could read them, right? But nobody set those permissions on anything … All of the source was writable, by anybody! It was just open …

“If you had an idea for an editor, you’d pull the editor out and you’d write on it and put it back … There was a mantra going around that, ‘You touch it, you own it.’”

Thompson provides an example: Bell Labs co-worker P. J. Plauger, with whom he later wrote the 1974 book “Elements of Programming Style.” Plauger was also a professional science fiction writer, Thompson remembers, “And whatever he was writing on was in his directory, right? So, we’d all go in there and be reading it as he’s writing it … and we’d all write back, ‘You ought to kill this guy, and move him over here and turn him green!’ or something.

“And he didn’t mind it, because that’s just the theory of Unix in those days …

“I think that generated a fellowship. Just the fact that it was like writing on a blackboard — everybody read it.”

And more of their Bell Labs experiments found their way into the world when some work on the later Plan 9 operating system found its way into the UTF-8 standard, which underlies most of today’s web connections.

After Bell Labs

Thompson left Bell Labs in 2000, after the breakup of the Bell system. (“It had changed; it was really different … You had to justify what you were doing, which is way above my pay grade.”) But his three decades there seemed to shine an influence over the rest of his life.

Thompson first moved on to a networking equipment company called Entrisphere, where he worked for six years — and a move to Google was the natural next step. The head at Entrisphere had already moved to Google, and was urging Thompson to follow him — and it turned out that Google CEO Eric Schmidt was an old friend who’s actually worked at Bell Labs in 1975. (Thompson says Google made him “an exceedingly good offer”…)

At Google Thompson worked “a little bit” on Android security. (“I found a couple of specific problems, but by and large, it was very well done”.) But eventually Thompson joined the three-person team that would create the programming language Go.

And he was doing the work with Rob Pike, who was one of his old comrades from Bell Labs nearly 30 years before!

YOUTUBE.COM/THENEWSTACK

Tech moves fast, don’t miss an episode. Subscribe to our YouTube

channel to stream all our podcasts, interviews, demos, and more.

Tell us your thoughts in comments! Tell us your thoughts in comments!

#️⃣ #Ken #Thompson #Recalls #Unixs #Rowdy #LockPicking #Origins

🕒 Posted on 1761549344