💥 Discover this trending post from Culture | The Guardian 📖

📂 **Category**: Documentary films,Aids and HIV,Film,Culture,LGBTQ+ rights,Transgender

📌 **What You’ll Learn**:

DIn the summer of 2020, at the beginning of the Covid pandemic, documentary filmmaker Matt Nadel returned to his home in Boca Raton, Florida. He remembers one of the evening walks he took with his father, Phil, while getting through those early months.

As they walked around the neighborhood, Nadel, now 26, said the prospect of a vaccine was exciting, but the idea of drug executives profiting from a devastating virus made him feel uneasy. Phil becomes concerned about the complex moral dilemma his son is in, and a waiter soon realizes that his father has been acting strangely.

“I think I should tell you something,” Phil said midway through, before explaining that in the early days of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, he had invested in what were known as “transient settlements.” Phil would buy life insurance policies for people dying of AIDS, often with only weeks or months to live, for a portion of the plan’s value in cash. For many, this has afforded them the ability to pay for food, rent and hospital bills as a debilitating illness has left them unable to work. For others, it was their opportunity to spend money on travel or experiences with the limited time they had left.

“I was thrown for a complete loop,” Nadel told The Guardian. “He was part of this industry, and the profits he made from it helped fund my childhood.”

For Nadel, the gay director, this put him into a “vortex” that did not begin with a desire to make a film. “I understand myself as someone who stands on the shoulders of AIDS activists who use their bodies to create a world where I can be healthy and receive pre-exposure prophylaxis treatments.” [pre-exposure prophylaxis] “Every morning,” he said, “I could also be relatively free as a gay man. A lot of the progress in gay rights came from the advent of the AIDS era, and here I was learning that my existence and my privilege were somehow contingent on the deaths of these same people.”

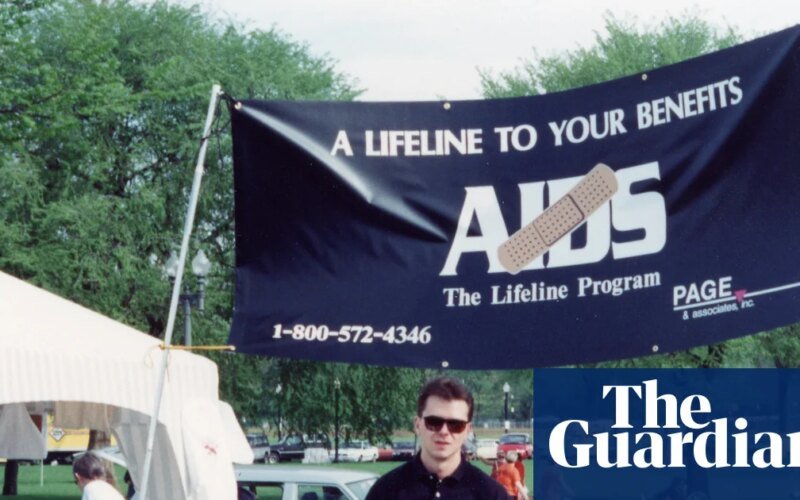

As the muddy history of the settlements through the height of the AIDS crisis begins to be investigated, the broad outlines of the film begin to emerge. The result is Nadel’s Oscar-shortlisted documentary short Cashing Out, which tells the story of how the cottage industry of buying life insurance policies was both terrible and liberating in equal measure.

One of the film’s main characters, Scott Page, inadvertently creates an early compromise when his partner, Greg, who has been living with AIDS, becomes progressively ill.

Short on cash, but armed with a solid life insurance policy, Page placed an ad in a local newspaper to see if someone could buy Greg’s plan in exchange for an advance. When a private investor reached out, the couple reached a “loose agreement” that allowed Greg to live out the time he had left with some financial security. The payment means they can also move into a home and get a golden retriever.

As dozens of old photos flash across the screen, you see a perfect slideshow of two people living a rich life: fixing up their house, lounging on the beach and laughing with friends. But it’s also a bittersweet record of Greg’s final months. Page eventually recalls how the money he had was “an absolute transformative” for his late friend, as he “saw the stress leave his body.”

However, the absurdity of getting a cash advance upon your death was not lost on Paige. And when he saw the peace and freedom he had given Greg before his death, he turned his energy to becoming a sinister go-between for dozens of other gay men — often without loved ones at their bedsides — who were dying from a disease that much of the federal government was shrouded in shame and prejudice. When Page began approaching banks and credit unions about participating in the investment scheme, they were skeptical and insisted that the payments should be to the families of the deceased. For Page, their arguments were not rooted in reality. “These people’s families turned away from them,” he recalls in the documentary.

This means that individuals make up most of the initial investor network when it comes to purchasing policies. They were provided with a patient ledger. On the one hand, the value of the policy and the dollar amount needed to purchase it outright, and on the other hand, the number of T cells of a person with HIV/AIDS and their life expectancy. Often, it served as a guarantee that payment was inevitable. The sicker the policyholder is, the faster the investor’s windfall will occur. Institutions quickly realized that these small individual investors were making a lot of money, and they changed their view.

Nadel structures his documentary like a magazine story taken in depth: poignant anecdotes, a rich—if harrowing—historical background, and diverse voices that show that while some people benefited from fleeting compromises, there were many who were left out of the conversation altogether.

Dede Chamblee, the pioneering advocate and activist, reminds us that for Black trans women with AIDS—who often did not have jobs that provided life insurance policies—a vital settlement was something they could only dream of.

One of the most harrowing moments in the documentary comes when Chamblee recalls her suffering during her illness, with only three T cells left, and how she imagined receiving compensation to live out her final days in peace. “I could have gone to the beach and stayed there until this was over,” she recalls. “It was not real at all,” she adds, expecting that she would end up buried in a wooden box in the “Pottery Field” with other unclaimed bodies.

Chamblee’s testimony is a shocking reminder that her experience living with AIDS is far removed from that of gay white men who have politics for sale. In cashing in, Nadel realized that the most marginalized people, especially sex workers of color, “don’t get an ounce of basic dignity when their death is imminent.”

But by the late 1990s, significant advances in antiretroviral therapy meant that people with HIV began to live longer lives, defying the odds and missing the expectations initially promised by online investors. “It was going well, so people weren’t dying all the time,” Page says, a glint of karmic joy in his eyes.

Eventually, those who bet on death stopped making easy money. Instead, they found themselves stuck paying premiums on insurance policies that would never be paid off. “I think they relied on this not being a pressing enough question for our world to answer,” Nadel said. “Then they were outraged when Act Up activists successfully pushed the government to develop and launch drugs quickly… Anyone who invested their entire retirement in drugs was making a really bad investment decision, and it’s no one’s fault but their own.”

Nadel filmed interviews with the people he photographed — Page, Chamblee, and Sean Stroup, a longtime survivor who founded POZ magazine — over the course of a year. Their unfiltered honesty eventually led him to engage with the story of his father’s investment in transit settlements. “I felt like they were completely putting themselves through this process,” he said. “And for me to have a secret about my relationship to this, which I was keeping from the public, was wrong.”

In a recent interview, Nadel said that although his thesis for the film has changed over time, it now seems clear and straightforward. “This has helped a lot of people, but I’m disgusted that it has to exist,” he said. Modern-day instability in access to health care in the United States — from the expiration of Covid-era Obamacare subsidies to the deep cuts in Medicaid funding expected over the next decade — means that disbursing the funds could serve as a historically specific and evergreen indictment of the country’s fragile social safety net, Nadel said.

“When the government refuses to do its part to take care of us, we have to come together and find creative ways to take care of each other,” he said. “The disease does not discriminate between people…so I want to encourage people who watch the film to find their strange companions in the struggle for survival.”

💬 **What’s your take?**

Share your thoughts in the comments below!

#️⃣ **#Cash #Advance #Death #Strange #Sick #World #Profiting #AIDS #Documentaries**

🕒 **Posted on**: 1769037062

🌟 **Want more?** Click here for more info! 🌟