🚀 Check out this must-read post from Culture | The Guardian 📖

📂 **Category**: Lucian Freud,Art,Art and design,Culture,Exhibitions,National Portrait Gallery

💡 **What You’ll Learn**:

AOne evening in 1951, at his home, Lucian Freud made three drawings of fellow artist Francis Bacon. Biographer William Feffer tells the tale as Freud told it to him: Bacon stood up, unbuttoned his trousers, rolled up his sleeves and rocked his hips a little, saying: “I think you ought to do this, because I think this is rather important.”

By Freud’s own admission, the older painter was provocative in more ways than just this pose: “I became very impatient with the way I was working. It was a limited, limited medium for me,” Freud told Pfeiffer. He said he felt his drawing prevented him from liberating himself, “and I think my admiration for Francis was the reason for that. I realized that by working the way I did, I couldn’t really improve. Maybe the change was nothing more than focus, but it enabled me to deal with the whole thing in another way.”

You trace with your eyes the curves and precision of these three line drawings and the word “limited” is the last adjective that comes to mind. They are great. What Freud’s comments belie is the relentless pursuit that gives all his work such power.

This trio is among 175 paintings and works on paper in the National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition Lucian Freud: Drawing in Drawing. For Freud, drawing was many things. It was how he wrote letters as a child, how he smashed canvases (a jagged, ghostly image disappearing under the paint), how he solved problems (going to the National Gallery late at night to look at specific works), and how he painted without paint (all those fleshy etchings from the 1980s onward). This was also often what he did after “painting himself from a canvas,” as his former assistant David Dawson put it. Museum curator Sarah Huggett points to several pen, ink and charcoal on paper items relating to the large interior panel, W11 (After Watteau), a massive canvas he painted between 1981 and 1983. Many of the drawings “were a response to the final drawing, not preparatory work,” Huggett says.

Dawson, who has worked for Freud since the early 1990s and is the last person to paint a portrait of him, says that painting after the fact was about the artist’s never-ending pursuit of a direct line from heart to eye to hand to canvas: “He’s discovering things, exploring, and it’s a faster way to explore with pencil or charcoal than the whole spectrum of oil.”

It is also the most accurate. “He always said you can never lie with drawing,” Dawson says. “As for paint, it’s an attractive medium, as you can smudge things a little bit, if you cut corners – which he never did, but you He can. You can fake it a little with paint. You can’t do that with drawing.

Lucian Freud: Drawing in drawing is At the National Portrait Gallery, London, Until May 4.

Pencil Case: Five images from the exhibition

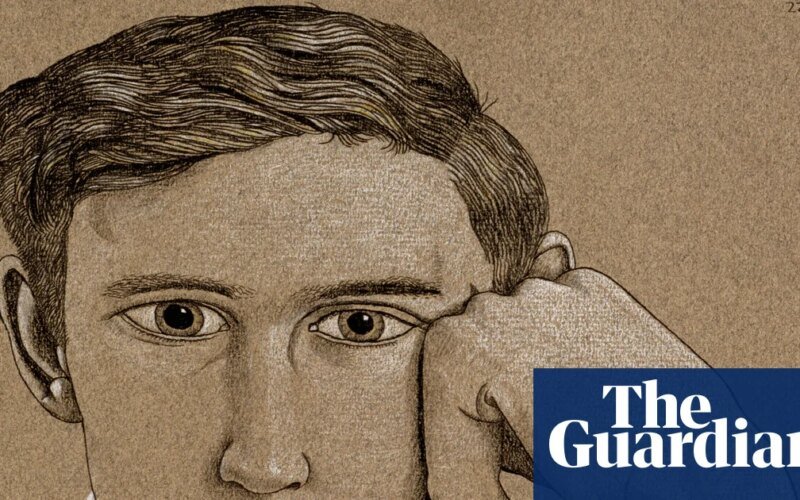

Portrait of a Young Man, 1944 (main image)

Howgate highlights artist John Craxton’s direct gaze here, and the startling detail in Freud’s rendering of the man’s hair, the weave of his jacket, and the soft folds in his tie. His use of white chalk on colored paper recalls Ingres, and art historian Herbert Read’s assessment of Freud as an “Ingres of existentialism.”

Bella in her Pluto shirt, 1995

An earlier version of this portrait of Bella Freud shows the artist’s daughter without a face. Freud’s engravings record various moments when he made a mark and then changed his mind, or, as here, when he had the printmaker rub the copper plate again until it was smooth so he could rework what he wasn’t happy with.

Girl in bed, 1952

“In the case of some artists, all the pictures they paint of other people are actually pictures of themselves. I think that’s not the case with Lucien,” says Huguet. Freud often talked about the importance of his subject’s inner life. They weren’t just blanks to fill. Instead, he made their private worlds tangible.

Head of Law, 2003

Freud worked standing less than a meter away from where his subject was lying in bed, on the floor, or sitting in a chair. “He would get very close to you, very close to you,” says Dawson. If his process is very internal, you are aware of his nervous anxiety. “It wasn’t comfortable. That made you as a babysitter a little nervous because he didn’t quite know…he was fighting with himself every day.”

David Hockney, 2002

The exhibition includes a selection of paintings that show the dialogue between Freud’s works on paper and on canvas. In this picture, Hockney walks into Holland Park to see Freud and sits “for 120 hours, as he likes to say,” Huggett says. He also made a drawing of Freud, which is also in the National Portrait Gallery’s collection, but, says Dawson, Freud gave David only 45 minutes “and then walked away”.

🔥 **What’s your take?**

Share your thoughts in the comments below!

#️⃣ **#Great #Artist #Paper #Lucian #Freuds #Magical #Drawings #Key #Great #Works #Lucian #Freud**

🕒 **Posted on**: 1770985999

🌟 **Want more?** Click here for more info! 🌟