✨ Check out this insightful post from Hacker News 📖

📂 Category:

✅ Here’s what you’ll learn:

Yesterday, LangChain published a critical advisory for a vulnerability I reported in langchain-core: CVE-2025-68664 / GHSA-c67j-w6g6-q2cm.

Earlier this year, my research focused on breaking secret managers in our “Vault Fault” work – systems that are explicitly designed to be the security boundary around your most sensitive credentials. One takeaway kept repeating: when a platform accidentally treats attacker-shaped data as trusted structure, that boundary collapses fast. This time, the system that “breaks” isn’t your secret manager. It’s the agent framework that may use them.

Why this vulnerability deserves extra attention:

- It’s in Core. This is not a specific tool bug, not an integration edge-case, and not a “some community package did something weird.” The vulnerable APIs (dumps() / dumpd()) live in langchain-core itself.

- The blast radius is scale. By download volume, langchain is one of the most widely deployed AI framework components globally today. As of late December 2025, public package telemetry shows hundreds of millions of installs, with pepy.tech reporting ~847M total downloads and pypistats showing ~98M downloads in the last month.

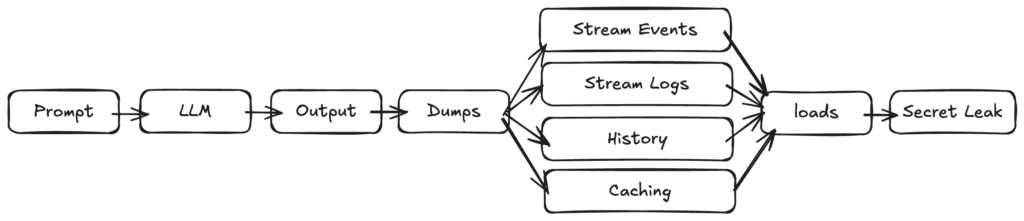

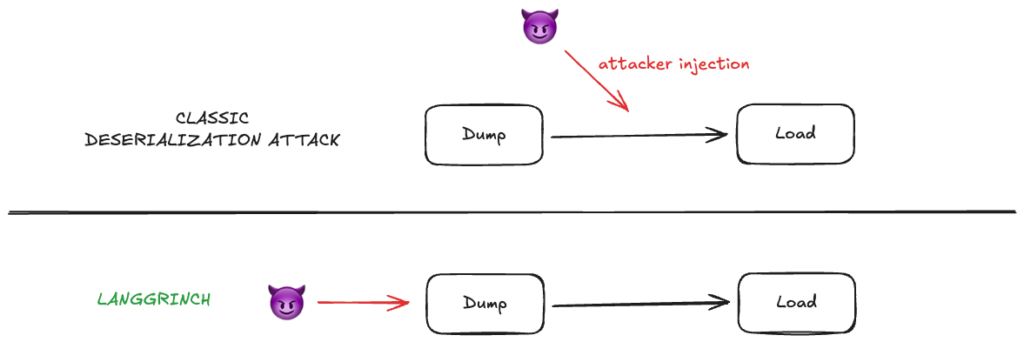

- One prompt can trigger a lot of machinery. The most common real-world path here is not “attacker sends you a serialized blob and you call load().” It’s subtler: LLM outputs can influence fields like additional_kwargs or response_metadata, and those fields can be serialized and later deserialized through normal framework features like streaming logs/events. Plainly, this means an exploit can be triggered by a single text prompt that cascades into a surprisingly complex internal pipeline.

Before you read further, patches are now released in versions 1.2.5 and 0.3.81. If you’re running LangChain in production, this one is trickier than it may seem; please update ASAP.

The short version of the bug

LangChain uses a special internal serialization format where dictionaries containing an ‘lc’ marker represent LangChain objects. The vulnerability was that dumps() and dumpd() did not properly escape user-controlled dictionaries that happened to include the reserved ‘lc’ key.

So once an attacker is able to make a LangChain orchestration loop serialize and later deserialize content including an ‘lc’ key, they would instantiate an unsafe arbitrary object, potentially triggering many attacker-friendly paths.

The advisory lists 12 distinct vulnerable flows, which are extremely common use cases, such as standard event streaming, logging, message history/memory or caches:

The most damaging outcomes include:

- Secret extraction from environment variables. The advisory notes this happens when deserialization is performed with secrets_from_env=True. Notably, this was the default until yesterday. 🙂

- Object instantiation within pre-approved namespaces (including langchain_core, langchain_openai, langchain_aws, langchain_anthropic…), potentially triggering side effects in constructors (network calls, file operations, etc.).

- Under certain conditions LangChain object instantiation may lead to arbitrary code execution.

This is categorized under CWE-502: Deserialization of Untrusted Data, with a CNA CVSS score of 9.3 (Critical).

My research story: how I stumbled into it

’Twas the night before Christmas, and I was doing the least festive kind of work: staring at serialization code and asking “wait… why is that trusted?”

Security research often looks dramatic from the outside. In reality, it is usually careful reading, small hypotheses, and a slow accumulation of “that’s odd” moments.

This one started the way many do at Cyata: with a simple question we ask constantly as we assess AI stacks for real-world risk:

Where are the trust boundaries in AI applications, and do developers actually know where those boundaries are?

LangChain is a powerful framework, and like most modern frameworks it has to move complex structured data around: messages, tool calls, streaming events, traces, caches, and “runnables.”

Reviewing previous research, there was already extensive research on LangChain tooling and integrations, but very few findings on the core library.

I started the research working backwards. Finding interesting locations (sinks), then figuring out how an attacker might reach them. Deserialization was an obvious target.

It took me quite a while to find something meaningful. But after a while, I found that assuming an attacker-controlled deserialization primitive, I could trigger blind SSRF that could be leveraged to exfiltrate environment variables (to be detailed soon). Because the outcome was limited to secret exfil, instead of my primary RCE goal, I kept auditing the deserialization, and took my time.

The bug wasn’t a piece of bad code, it was the absence of code. dumps() simply didn’t escape user-controlled dictionaries containing ‘lc’ keys. A missing escape in the serialization path, not the deserialization.

It’s much easier to spot something wrong than to notice something missing, especially when you’re auditing load(), not dumps(). In one of the most scrutinized AI frameworks. For two and a half years.

From there, the investigation became a structured exercise:

- Identify where untrusted content (mostly arbitrary dictionaries) gets serialized (LLM outputs, prompt injection, user input, external tools, retrieved docs).

- Identify when that serialized data gets deserialized.

- Identify what an attacker can achieve from arbitrary object instantiation.

At that point, the core finding was clear and actionable enough to responsibly report: there was an escaping gap in dumps() / dumpd() around ‘lc’ key dictionaries.

The advisory later captured what we often see in practice: fields like additional_kwargs and response_metadata can be influenced by LLM output and prompt injection, and those fields can get serialized-deserialized in many flows.

To the LangChain team’s credit: the response and follow-through were decisive, not just patching the bug but also hardening defaults that were too permissive for the world we’re in now.

The LangChain project decided to award a $4,000 USD bounty for this finding. According to huntr, the platform where LangChain operated its bounty program, this would be the maximum amount ever awarded in the project, with bounties so far awarded up to $125.

Technical deep dive

Background: the “lc” marker and why it exists

LangChain serializes certain objects using a structured dict format. The ‘lc’ key is used internally to indicate “this is a LangChain-serialized structure,” not just arbitrary user data.

This is a common pattern, but it creates a security invariant: Any user-controlled data that could contain ‘lc’ must be treated carefully. Otherwise, an attacker can craft a dict that “looks like” an internal object and trick the deserializer into giving it meaning.

The patch makes the intent explicit in the updated documentation: during serialization, plain dicts that contain an ‘lc’ key are escaped by wrapping them.

This prevents those dicts from being confused with actual LangChain serialized objects during deserialization.

The allowlist: what can be instantiated

LangChain’s load()/loads() functions don’t instantiate arbitrary classes – they check against an allowlist that controls which classes can be deserialized. By default, this allowlist includes classes from langchain_core, langchain_openai, langchain_aws, and other ecosystem packages.

Here’s the catch: most classes on the allowlist have harmless constructors. Finding exploitable paths required digging through the ecosystem for classes that do something meaningful on instantiation. The ones I found are detailed below, but there may be others waiting to be discovered.

The exfiltration path

LangChain’s loads() function supports a secret type that resolves values from environment variables during deserialization. Before the patch, this feature secrets_from_env was enabled by default:

if (

value.get("lc") == 1

and value.get("type") == "secret"

and value.get("id") is not None

):

[key] = value["id"]

if key in self.secrets_map:

return self.secrets_map[key]

if self.secrets_from_env and key in os.environ and os.environ[key]:

return os.environ[key] # <-- Returning env variable

return NoneIf a deserialized object is returned to an attacker, for example message history inside the LLM context, that could leak environment variables.

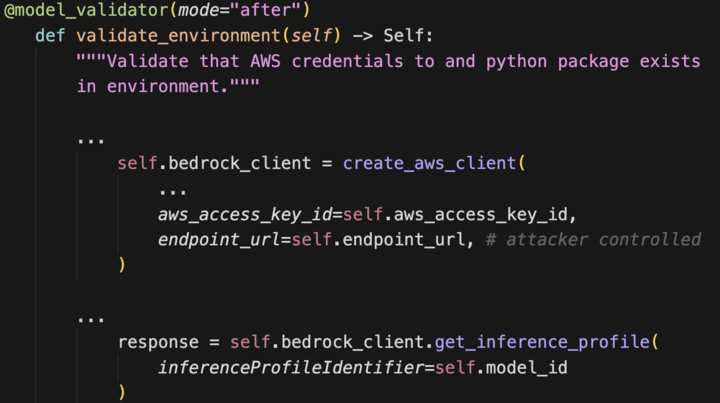

But the more interesting path is an indirect prompt injection. Even an attacker who cannot see any LLM responses can exfiltrate secrets by instantiating the right class. ChatBedrockConverse from langchain_aws is both in the default allowlist of loads and makes a GET request on construction.

The GET endpoint is attacker-controlled, and a specific HTTP header can be populated with an environment variable via the secrets_from_env feature.

This validator runs when ChatBedrockConverse is instantiated. The attacker controls endpoint_url, triggering an outbound request. Combined with secrets_from_env, the aws_access_key_id header can be populated with any environment variable – not just AWS keys.

We are intentionally not publishing a copy-paste exploit here, to give time for security teams. In a few months, the Huntr website will publish them automatically.

Code Execution via jinja2 templates

Among the classes in the default loads() allowlist is PromptTemplate. This class creates a prompt from a template, and one of the available template formats is Jinja2.

When a template is rendered with Jinja2, arbitrary Python code can run. We did not find a way to trigger this directly from the loads() function alone, but if a subsequent call to the deserialized object triggers rendering, code execution follows.

We suspect there may be paths to direct code execution from loads(), but we have not confirmed one yet. If you have a solid idea or a lead worth testing, we’d love to hear from you – this is exactly where the security community helps turn hypotheses into proof. 🤝

Also worth noting: in past versions, the Chain class was also in the allowlist. That class has special features that might have enabled a flow to template rendering.

Who is affected? The practical checklist

Your application is potentially exposed if it uses vulnerable langchain-core versions. Here are some of the most common vulnerable patterns (12 flows have been identified in total):

- astream_events(version=”v1″) (v1 uses the vulnerable serialization; v2 is not vulnerable)

- Runnable.astream_log()

- dumps() / dumpd() on untrusted data, followed by load() / loads()

- Deserializing untrusted data with load() / loads()

- Internal serialization flows like RunnableWithMessageHistory, InMemoryVectorStore.load(), certain caches, pulling manifests from LangChain Hub (hub.pull), and other listed components in the advisory

That said, the system’s behavior is complex enough that it’s risky to assume a quick code-path review will catch every reachable variant. The safer course is to upgrade to a patched version and not assume you’re in the clear until you do.

Also, the advisory calls out what I consider the most important real-world point:

The most common attack vector is through LLM response fields like additional_kwargs or response_metadata, which can be controlled via prompt injection and then serialized/deserialized in streaming operations.

This is exactly the kind of “AI meets classic security” intersection where organizations get caught off guard. LLM output is an untrusted input. If your framework treats portions of that output as structured objects later, you must assume attackers will try to shape it.

Defensive guidance: how to respond in production

1) Patch first (this is the fastest risk reduction)

Upgrade langchain-core to a patched version. If you are using langchain, langchain-community, or other ecosystem packages, validate what version of langchain-core is actually installed in production environments.

2) Assume LLM outputs can be attacker-shaped

Treat additional_kwargs, response_metadata, tool outputs, retrieved documents, and message history as untrusted unless proven otherwise. This is especially important if you stream logs/events and later rehydrate them with a loader.

3) Review deserialization features like secret resolution

Even after upgrading, keep the principle: do not enable secret resolution from environment variables unless you trust the serialized input. The project changed defaults for a reason.

The LangChainJS parallel

Based on my report, there is a closely related advisory in LangChainJS (GHSA-r399-636x-v7f6 / CVE-2025-68665) with similar mechanics: ‘lc’ marker confusion during serialization, enabling secret extraction and unsafe instantiation in certain configurations.

If your organization runs both Python and JavaScript LangChain stacks, treat this as a reminder that the pattern travels across ecosystems: marker-based serialization, untrusted model output, and later deserialization is a recurring risk shape.

Why this matters beyond LangChain

We are entering a phase where agentic AI frameworks are becoming critical infrastructure inside production systems. Serialization formats, orchestration pipelines, tool execution, caches, and tracing are no longer “plumbing” – they are part of your security boundary.

This vulnerability is not “just a bug in a library.” It is a case study in a bigger pattern:

- Your application might deserialize data it believes it produced safely.

- But that serialized output can contain fields influenced by untrusted sources (including LLM outputs shaped by prompt injection).

- A single reserved key used as an internal marker can become a pivot point into secrets and execution-adjacent behaviors.

At Cyata, our work is to help organizations build visibility, risk assessment, control, and governance around AI systems – because if you can’t quickly answer where agents are running, which versions are deployed, and what data flows through it, you’re effectively flying blind when advisories like this land.

What this teaches us about AI governance

If you are a security leader reading this, here is the uncomfortable truth:

Most organizations cannot currently answer, quickly and confidently:

- Where are we using agents?

- Which versions are deployed in production?

- Which services have access to sensitive secrets?

- Where do LLM outputs cross those boundaries?

That is not a “developer problem.” It is a visibility and governance problem.

And that is where Cyata comes in.

How Cyata helps: visibility, risk assessment, control, governance

At Cyata, we focus on a practical outcome: reducing AI and agent risk without slowing down builders. Vulnerabilities like this one are rarely “just a patch.” They expose gaps in how teams discover where agents run, understand real trust boundaries, and enforce safer defaults across fast-moving frameworks.

Visibility

Know what is running, where, and how it is wired.

Answer the first CVE question quickly: are we exposed, and in which flows?

Discover agent runtimes and integrations across environments (IDEs, CI, services, worker jobs, hosted agents).

Track frameworks, packages, and versions in use.

Risk assessment

Prioritize what matters based on real-world blast radius, not just “library present.”

Support faster triage: what is internet-facing, what touches secrets, what runs with elevated credentials.

Identify the highest-risk paths: untrusted content flowing into privileged contexts (services with secrets, broad tool permissions, prod network access).

Highlight where “structured fields” can cross trust boundaries (metadata, tool outputs, streamed events, cached artifacts).

Control

Reduce exposure even before every dependency is patched everywhere.

Encourage safer operational defaults: least privilege, isolation boundaries, and policy checks that scale across teams.

Enforce guardrails around risky patterns (for example: deserializing untrusted data, permissive object revival, unsafe streaming-to-cache-to-rehydrate flows).

Gate or restrict sensitive capabilities in untrusted contexts (for example: secret access via environment, high-privilege tool execution, or running risky code paths in privileged workers).

Governance

Make “safe agent usage” repeatable, auditable, and hard to drift.

- Define policies for approved frameworks, versions, and configurations.

- Track and time-box exceptions with owners and rationale.

- Monitor for drift and risky feature usage over time, with an audit trail that supports security reviews and compliance.

When a Christmas-week advisory drops, the goal is not heroics – it’s calm, controlled response backed by real inventory and enforced guardrails.

Disclosure Timeline

Report submitted via Huntr – December 4th, 2025

Acknowledged by LangChain maintainers – December 5th, 2025

Advisory and CVE published – December 24th, 2025

The Control Plane for Agentic Identity

Share your opinion below! What do you think?

#️⃣ #Christmas #Secrets #LangGrinch #hits #LangChain #Core #CVE202568664 #Cyata

🕒 Posted on 1766692999