🔥 Discover this awesome post from Culture | The Guardian 📖

📂 **Category**: Books,Culture,Netherlands,History books,Fiction,Travel writing

📌 **What You’ll Learn**:

IIn the opening of his famous book Roads to Santiago, Dutch author Cees Nooteboom wrote that “there are some places in the world where one’s arrival or departure is mysteriously magnified by the feelings of all those who have arrived and departed before.” “Travellers have existed in all ages,” Nottebohm continues, “but only for some is there a special sadness: the sadness of one who leaves with no hope of returning.” For them, the trip abroad becomes life.

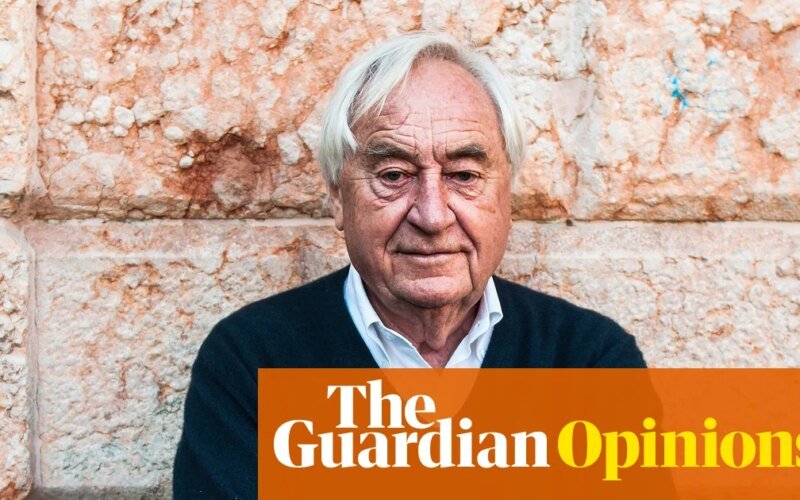

Noteboom, who was born in the Netherlands in 1933 and died this week at the age of 92, was drawn to what could be understood through the “perspective of movement.” In a body of work that includes some 60 books of fiction, poetry, reportage, and travel writing, of which only about a dozen have been translated into English, he has become a chronicler of departures. In the following stories (translated by Ina Rilke), Nomad Hotel (translated by Anne Kielland), Foxes Come at Night (translated by Ina Rilke) and Paradise Lost (translated by Susan Masotti) Nottebaum, his characters and subjects take to the road. They glimpse history melting away from memory, and the horrors of the past resurfaced, again and again, in chilling ways. Nottebohm was 12 years old when his father was killed during World War II; He said his first childhood memories were of the bombings and the devastation that followed.

In the opening of his great novel All Souls’ Day (translated by Susan Masotti), director Arthur Dunne notes that the Dutch word for history, Geschideniscontains the suffix NISIt is a word that also means status. He believes that the right place in history may be a place where things are kept or found. In Nottebohm’s book, history is inscribed everywhere: in love affairs, in the aging body, in monuments, in conversation, in silence, in stone. The writing is wry, clear, often comical, and always attentive.

Nooteboom’s work holds a personal and unusual place in my life. More than 20 years ago, I arrived home from college to find a message on my answering machine. Listening, I realized that something terrible had happened. I tried to contact my family but couldn’t reach anyone. I sat down, frightened, and opened the book closest to me, All Souls’ Day. I only had 20 pages left to read, so I hid inside these pages, reading slowly as if a book of fiction could keep me from the next hour, or even the next moment. When the phone rang again, I had six pages left. I got up to answer him. I was told that my mother died. She had suffered heart failure a few hours earlier, at night. She was on a business trip, and when her colleagues found her, she was gone.

Soon after, I left Canada and lived for a while in the Netherlands before starting a life of moving around. For years, I kept All Souls’ Day with me even though I had no intention of ending it. It was a piece of the past that I carried. But 15 years later, I took it off the shelf and found where it left off.

In the final pages of the novel, Nottebohm describes a cemetery where hundreds of women, accompanied by their children, tend the graves of their loved ones. They embrace each other. The cemetery floats freely, gathering women, children and flowers. It is not bound by the earth, it is a “dream world that extends to the horizon” and a “ship of joy.” Arthur believes you never completely leave the dead. Someone must bring flowers, and someone must celebrate the only day, November 2, that belongs to all souls.

Through his books, Nottebohm taught me how we can write about history and how we also take responsibility for the present. His voice is full of passion, intelligence and sadness. For most of his life, he repeatedly returned to Spain. In this country, which seemed to hold a mirror to his innermost self, he wrote about the journeys that defined him.

Among those trips was a trip to Iran in the spring of 1975. “The key word is old,” he says. “You approach Persia with blind Western arrogance and face thousands of years of history without any reference. The last thing you ever learned was Xerxes, but what about all those centuries that came after that?” In the city of Isfahan, as he tried to describe a dome made of stone and earth but somewhat transparent, he almost gave up on the task: “I can’t understand it.” But then, moving anxiously, he enters a forest of stone pillars. He writes: “There is light everywhere, floating, gathering, piercing, and stitching; the stones themselves are embroidered with it, doves fly in and out of it.” Even the wealthiest dynasties, he says, can turn out to be “nothing more than a scratch on the great stone of history.” He writes about the Shah, about political prisoners, about torture and grief, and about what might happen next.

Who am I to be here? He often asks. In Nomad Hotel, he describes the traveler as follows: “It is a game. He knows it to be true and untrue. He collects lies to make a plausible past. The game is called continuity, and contrary to what others think, he does not reject the contemporary world, but wishes to support it—memory and recognition are the tools.” But even this awareness can cloud our sight, as when we move closer to examine details and the world around us dissolves. Noteboom notes that our journeys may demand more than we know how to give: “To find what he is looking for, he gains an extra forehead covered with eyes.”

Perhaps all of Nooteboom’s works revolve around historical areas, where much lies in wait or is lost forever. He wrote that learning to be a traveler means knowing that you are absence and presence at the same time.

Although Nottebohm’s book has been praised for decades and repeatedly mentioned as a Nobel Prize contender, it appears not to have been widely read in English. Readers like me found him by chance, or by good fortune, when his Dutch and German friends brought his works into our hands. His novel came to me when I needed it most, and I returned to it, and to all of his books, as if in an ever-lively conversation. I feel like I’ve lost a friend. But Dan reminds himself at the end of All Souls’ Day: Someone’s got to bring flowers. Here then is my king.

🔥 **What’s your take?**

Share your thoughts in the comments below!

#️⃣ **#Cees #Nootebooms #rough #wit #melancholy #needed #books**

🕒 **Posted on**: 1771037255

🌟 **Want more?** Click here for more info! 🌟