✨ Read this trending post from Hacker News 📖

📂 **Category**:

💡 **What You’ll Learn**:

The jury is out on the effectiveness of AI use in production, and it is not a pretty picture.

- Teams using AI completed 21% more tasks, yet company-wide delivery metrics showed no improvement (Index.dev, 2025)

- Experienced developers were 19% slower when using AI coding assistants—yet believed they were faster (METR, 2025)

- 48% of AI-generated code contains security vulnerabilities (Apiiro, 2024)

To understand why, we have to take a closer look at the day-to-day software development. Consider this point raised in a colorful exchange on r/ExperiencedDev:

A developers’ job is to reduce ambiguity. We take the business need and outline its logic precisely so a machine can execute. The act of writing the code is the easy part. Odds are, you aren’t creating perfect code specs into tickets, even with meeting notes, because developers will encounter edge cases that demand clarification over the course of implementation…

There are two key points raised in this comment. Firstly, coding assistants require clearly-defined requirements in order to perform well. Secondly, edge cases and product gaps are often discovered over the course of implementation.

These two facts come head-to-head in the application of coding agents to complex codebases. Unlike their human counterparts who would and escalate a requirements gap to product when necessary, coding assistants are notorious for burying those requirement gaps within hundreds of lines of code, leading to breaking changes and unmaintainable code.

As a result, more overhead is spent on downstream code reviews (Index.dev, 2025) and fire-patching security vulnerabilities (Apiiro, 2025).

In other words, the use of AI in production settings often increases ambiguity and reduces code reliability, directly contradicting the objective of developers.

The picture is not without optimism. Some experienced engineers report transformative results: one principal engineer at Google claimed AI “generated what we built last year in an hour”; Boris Cherny, creator of Claude Code, described a month where he “didn’t open an IDE at all” while the model “wrote around 200 PRs, every single line.” The optimistic case is that developers evolve from coders into product engineers, focusing on architecture and product thinking while AI handles implementation.

This however reflects the experience of seasoned developers who have both the technical depth to review AI output critically and the autonomy within their organizations to straddle product and engineering.

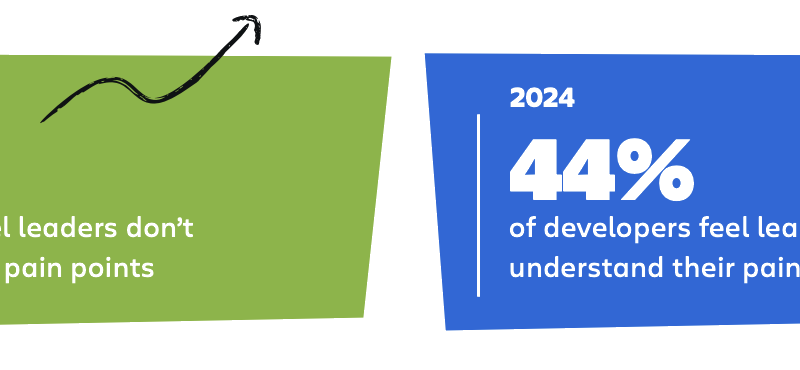

For much of the software engineering workforce, the junior and mid-level engineers at banks, healthcare, and government agencies, there’s much less wiggle room. They are sandwiched between the unreliability of AI output and the increased expectation from management to ship faster, resulting in a rapidly widening empathy gap between developers and product owners.

The product context often goes through multiple layers (end users -> marketers -> product managers) before landing on their lap, necessitated by the separation of responsibilities within an organization and the unique demands of their industries. The effective use of coding agents may require a level of team coordination that simply does not justify the gains in technical output.

But what if we have simply been approaching the problem from the wrong angle? Suppose we tackle the pain points of software development from first principles, can we come up with solutions that organically decrease ambiguity and reliably increase engineering velocity in production?

Consider how developers spend their time (IDC, 2024):

Only 16% of a developer’s time goes to writing code. The rest? Security and code reviews, monitoring, deployments, requirements clarification—operational work that keeps the lights on but doesn’t ship features.

Here’s the irony: AI coding assistants save developers roughly 10 hours per week, but the increase in inefficiencies in the other parts of the development lifecycle almost entirely cancelled out such gains (Atlassian, 2025). Here’s a comment from the earlier cited Redditor.

They produce legitimate-looking code, and if no one has had the experience of thinking through the assumptions and then writing them into code – considering the edge cases- it’ll be lgtm’d and shipped. You’re shifting the burden of this feedback cycle to the right, after the code is output, and that makes us worse off since code is tougher to read than write.

There’s a name for misalignment between business intent and codebase implementation: technical debt. The use of coding agents without careful delineation of their scope and responsibilities is threatening to accelerate tech debt accumulation.

Hammering AI code generation on existing codebases doesn’t solve the problem, because contrary to what the label “tech debt” may suggest, most tech debt isn’t actually created in the code, it’s created in product meetings. Deadlines. Scope cuts. “Ship now, optimize later.” Those decisions shape the system, but the reasoning rarely makes it into the code.

[Engineers] occasionally have access to complete data; at other times, they must work with limited information. They might be conscious of uncertainties surrounding their evidence, but frequently they are not. Competing social, financial, and strategic priorities influence the tradeoffs in unexpected ways. — Rios et al., 2024

How can we make this context-sharing and decision-making process less chaotic? We surveyed developers across different roles and team sizes regarding their product-engineering handoff process. The results were overwhelming: the majority discover unexpected codebase constraints weekly, after already committing to a product direction and the corresponding architectural implementation. When asked what would help most, two themes dominated:

- Reducing ambiguity upstream so engineers aren’t blocked waiting on product clarification mid-implementation

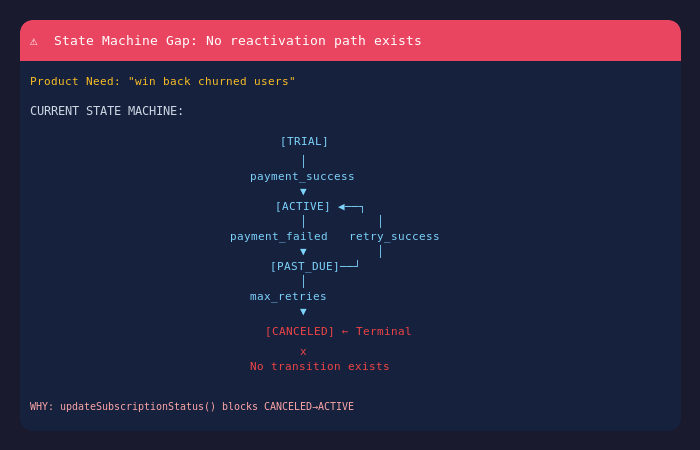

- A clearer picture of affected services and edge cases to allow for more precise feature scoping and time allocation

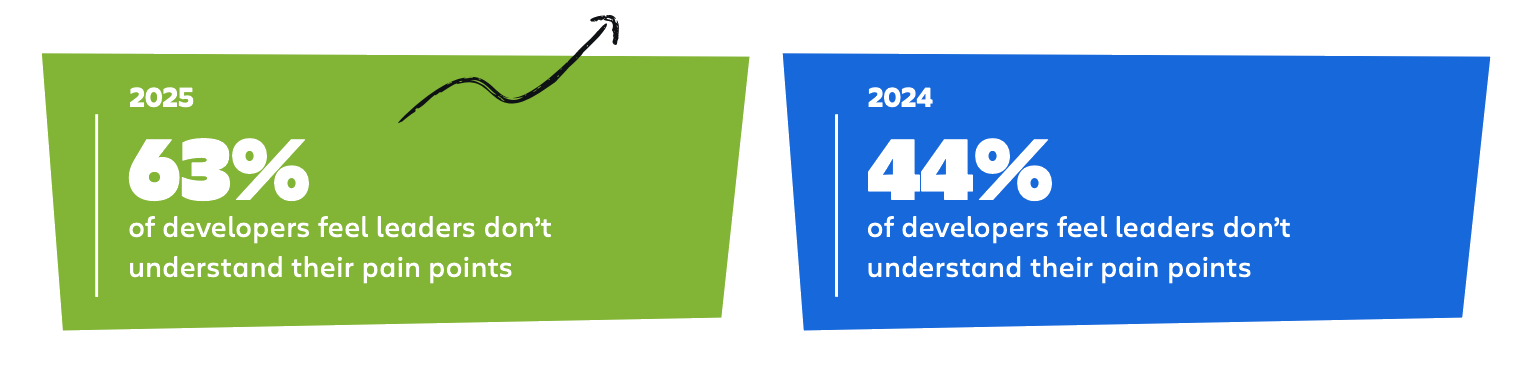

When asked which engineering context would be most valuable to surface during product discussions, three categories stood out: state machine gaps (unhandled states caused by user interaction sequences), data flow gaps, and downstream service impacts.

Identifying how feature updates affect existing architectures and data flow is rated most desirable among engineering contexts to be surfaced after a product meeting.

This aligns with decades of SDLC research showing that the costliest defects stem from misalignment between requirements and architecture, and such gaps often go unnoticed until it is too late.

Luckily, the advancement of coding LLMs works in our favor here. Whereas generating fully-functional code through natural language prompting is prone to errors due to the aforementioned context problem, the reverse process, mapping out existing code structures and inferring how they may be impacted by a specific requirement, is much more tenable with recent models.

From this vantage point, the possibilities to improving the developmental lifecycle is endless. Some suggested real-time display of engineering context during a meeting to help steer discussions; Others requested a code review bot that detects the discrepencacy of code implementation with stated product/business requirements.

All-in-all, developers are eager to try out new tools that augment the existing way of doing things, provided they retain flexibility over when such tools are deployed. There is also little reservation against having longer but more fruitful product meetings: it is the difficulty conveying blockers that is the source of frustration.

At Bicameral, we are committed to taking this pragmatic approach to alleviating software development pains, and move beyond lab benchmarks to investigate the most effective way to deploy AI in the wild.

Our thesis is that LLMs could be a huge boon both for the industry and for individual developers—channeling the unrivaled human capacity to operate under uncertainty and adapt—provided the technology is developed with human needs in mind.

If you’re a developer, we want to learn which types of context hurt most when they’re missing from discussion, based on your unique experience.

Survey link: https://form.typeform.com/to/w4rPXoPD

References

- Index.dev. (2025). AI Coding Assistant ROI: Real Productivity Data.

- METR. (2025). Measuring AI’s Ability to Complete Long Tasks.

- Apiiro. (2024). 4x Velocity, 10x Vulnerabilities: AI Coding Assistants Are Shipping More Risks.

- IDC. (2024). How Do Software Developers Spend Their Time?

- Atlassian. (2025). State of Developer Experience Report.

- Rios, N., et al. (2024). Technical Debt: A Systematic Literature Review.

- Pragmatic Engineer. (2025). When AI Writes Almost All Code.

🔥 **What’s your take?**

Share your thoughts in the comments below!

#️⃣ **#Coding #assistants #solving #wrong #problem**

🕒 **Posted on**: 1770100823

🌟 **Want more?** Click here for more info! 🌟