🚀 Explore this must-read post from Culture | The Guardian 📖

📂 Category: Frida Kahlo,Art and design,Culture,Art,Mexico,Americas,World news

💡 Main takeaway:

TIt may be Frida Kahlo’s biggest year yet. There has recently been a museum opening in Mexico City to celebrate her life and work. There the Art Institute of Chicago is showing her work for the first time. And then, in Shenzhen, there is the show that marked its debut in China. All this “Fridamania” takes place between last year’s big screen documentary “Frida” and next year’s exhibitions in London and the US.

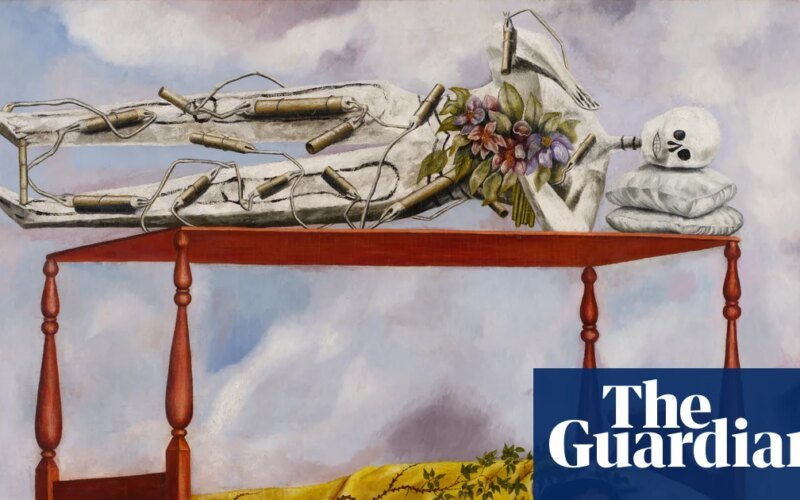

What’s more, to top it all off, Sotheby’s auction in New York today is almost certain to make Kahlo break records. Her 1940 painting “The Dream” (Bed) is expected to sell for between $40 million and $60 million, which will dwarf the previous record for a female artist, set by Georgia O’Keeffe’s “Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1” in 2014, which sold for $44.4 million.

They are enough scraps of paper to obscure a report published in April by Hilda Trujillo Soto, who served as deputy director and then director from 2002 to 2020 at Casa Azul, as the Frida Kahlo Museum is known in Mexico. At the conclusion of her five-year independent investigation after leaving the museum, Trujillo Soto alleged the disappearance of two oil paintings and eight drawings among the museum’s 1957 and 2011 inventory, as well as at least six pages extracted from Kahlo’s photo diaries. In summing up these “crimes against the property of the nation,” Trujillo Soto declared: “As a Mexican society, we owe an explanation.”

One of the alleged missing works, the 1952 Peoples’ Conference for Peace, was sold by the Mary Ann Martin Fine Art Gallery in New York for $2.66 million at auction in 2020. According to the Wayback Machine online archive, the gallery was also featuring another allegedly stolen Kahlo painting, the 1954 Self-Portrait Inside a Sunflower, with the provenance listed only as “Private Collection, Dallas.” The gallery did not respond to requests for an interview on this topic.

Trujillo Soto’s broader conclusions have been supported by Helga Bregnitz Buda, a Kahlo expert based in Berlin. “Many things have disappeared from Casa Azul,” she told reporters in response to Trujillo Soto’s report.

“Frida painted her reality — even when it was uncomfortable,” Trujillo Soto told me. “I wrote my stuff down. Annoyance and all.”

Kahlo is worshiped in Mexico, where her works are heavily protected, ostensibly, by heritage laws. She is to Mexico what Turner is to Britain or Michelangelo is to Italy. But instead of investigating Trujillo Soto’s catalog of lost works – if only to discredit it – the government obstructed the case. The three heads of the Culture Ministry’s Transparency Unit chose not to be transparent, deferring entirely to representatives of the state-run Bank of Mexico, which manages the Kahlo Fund. These bank officials did not respond to interview requests.

But the institution accused Trujillo Soto of malice. She said in a statement that she “never filed an official complaint,” and added: “On the contrary, their contract was terminated after irregularities were discovered in their management and their use of assets under their care,” which she in turn denies.

The day after Trujillo Soto’s allegations, Inbal, the agency charged with protecting and promoting Mexican art as heritage, said it had “granted no permission for the final export of works by Mexican artists.” [Kahlo]But she did not otherwise comment on potential foreign sales of the museum’s inventory.

“It is a strategy of silence,” said Trujillo Soto of the Culture Ministry. “If I were a man, my report would be an analysis. But I’m a woman, so Mexican masculinity has decided that what I’m saying is just gossip.”

In a statement, Casa Azul called Trujillo Soto’s allegations “baseless, false and disturbing.” [lacking] ‘Verifiable evidence’ But they did not amplify their position with evidence of their own. When Perla Labarthe, the museum’s current director, was asked to allay fears by proving that the missing works were still part of the museum’s inventory, she did not respond.

“I think after I die, I will be the biggest piece of shit in the world,” Kahlo said. Casa Azul increasingly appears to be ground zero for Kahlo’s storm. In fairness, the government and museum are already challenging the last will of Diego Rivera, the muralist who married, divorced and remarried Kahlo before she widowed him. It will order that “under no circumstances or pretext shall objects belonging to heritage be removed from the building.”

Museums sometimes engage in a spin-off, the process of selling artworks to pay costs, debts, renovations, or simply to line pockets. It may not be reported to cover modesty or humiliation. Revoking unauthorized access is probably the most bureaucratic euphemism for theft.

Interpol officials declined to discuss the matter, but law enforcement agents familiar with the details — who requested anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly — said the Mexican government has not yet requested Interpol’s help, and Interpol can only act at the request of its member governments.

Likewise, Julian Radcliffe, head of the London-based Art Loss Register, which cited four disputed Kahlus paintings in circulation, said: “The museum has not registered any losses with us, but that is not surprising as museums are reluctant to acknowledge lost items and, of course, there are many more losses from internal theft by museum curators from stock or stores than from external theft of items on display.”

Robert Whitman, a retired chief investigator with the FBI’s art crimes team, expressed surprise that the Mexican government had not raised more alarms – especially since the country’s previous presidency had prioritized the repatriation of works of art so successfully. “Mexico has to do its due diligence,” he said.

The reluctance to report missing artworks can be a source of institutional embarrassment or outright corruption, says Christopher Marinello, an art lawyer who founded Art Recovery International. Even in the usual chaos and drama surrounding art theft, he added, “Mexico is a whole other problem. We worked cases and fought to get police reports, and then we discovered that members of the local police force were the prime suspects in committing the theft.”

A 2015 Sotheby’s Art Institute analysis of Mexican heritage laws and their impact on the art market found that works by heritage-listed artists have been suppressed in Mexico to at least half their global value. Mexican auction houses have complained to lawmakers that heritage restrictions are dampening business by up to 30%, as buyers view their private property as an intrusive co-custody with the government.

So Casa Azul’s lack of investigation is troubling amid an abundance of motives and suspects for art theft. Mexican auction houses, buyers, curators, galleries and police all have vested interests in the underground heritage market. At the same time, it is not just Interpol that cannot act alone. Art market observers cannot do that.

“To our knowledge, there have been no formal or legal accusations substantiating claims of stolen works,” says Raul Zorrilla, CEO of Curemanzotto, one of Mexico City’s most respected galleries — which eschews all secondary markets, including Kahlo, in favor of living artists. “We prefer to ground any discussion in frameworks of law, source verification, and institutional process rather than speculation.” Earlier this week in New York, Christie’s auctioned Kahlo the Minor. It sold for just $7.2 million, probably because it’s small in size and not a portrait (it’s a storefront painting in Detroit). However, $7.2 million is still a huge amount. In 2021, Kahlo’s 1949 self-portrait “Diego and I” sold for $34.9 million, more than quadrupling the previous high of $8 million for a Kahlo auction, and also broke the widest record for Latin American art held since 2018 by a $9.76 million painting by Rivera.

Such blockbuster auctions would be as dangerous to Kahlo’s legacy as any theft. “The criminal element doesn’t have a lot of imagination,” says Noah Charney, a doctoral student at the University of Cambridge who studies the history of art theft. “They steal what they recently read about as being of high value.” And not just thieves. Collectively, he said, we share “an unconscious understanding that if this artist is worth stealing, they must be very good.”

At her first exhibition – in New York in 1938 – Kahlo happily sold 12 of the 25 works. During her lifetime, she was praised by the art legends of her time: Kandinsky, Miró, and Picasso. Surrealist artist André Breton called her art “a ribbon around a bomb.” She didn’t like it, and called them all “art whores.”

Kahlo’s ideals – of communism, feminism, hedonism, intimacy, magic, queerness, romance, truth and trust – were intended to arouse uncertainty in audiences. Now, more than 70 years after her death, the art market is dealing with Kahlo’s own doubts of its own making.

⚡ Share your opinion below!

#️⃣ #Frida #Kahlo #scandal #Frida #Mania #reaching #heights #today #lost #masterpieces #Frida #Kahlo