🚀 Check out this must-read post from Culture | The Guardian 📖

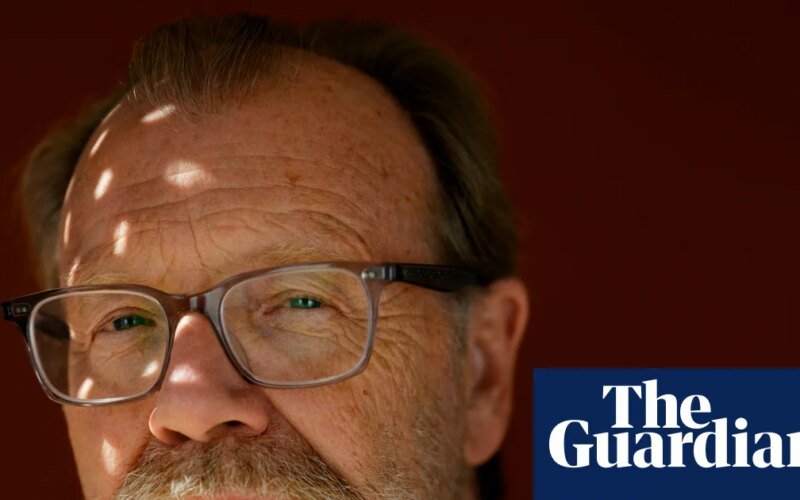

📂 **Category**: Fiction,Books,Culture,George Saunders

✅ **What You’ll Learn**:

gGeorge Saunders returned to Bardo, and was probably stuck there. Vigil, his first novel since the 2017 Booker Prize-winning Lincoln in the Bardo, returns to that indeterminate space between life and death, comedy and sadness, moral quest and narrative trickery. Once again, the living are largely absent, and the dead are curious and talkative. have a bone to pick.

They meet at the deathbed of oilman, KJ Boone. He’s a post-war primer: long-lived, filthy rich, and very pleased with himself. “A constant flow of contentment, even triumph, in regard to all that he was able to see, cause, and create flowed through him.” Boone is quiet in his final hours, which is enviable. He seems destined to die exactly as he lived, untroubled by self-reflection. But when his body falters, his mind becomes permeable to ghosts, and they have work to do. The businessman has profited greatly from climate denial, and there is still time for him to confess his fossil fuel sins before the lights go out.

Our narrator, Jill Blaine, is a spectral death doula. She’s helped hundreds of souls ease their way out of their bodies, and she’s good at it, partly because no one else has done the job (its ending was… explosive). But Boone is a prickly and unrepentant man; Confident in his brilliance, and exempt from the petty scruples of “mere earthlings.” What is the state’s role here: to comfort the dying man, or to correct the moral record? When does mercy become complicity?

Reading the post-Christmas vigil does not help. The ingredients here are unavoidably Dickensian: a crooked old bastard, ghostly visitations, and a soul (or two) at stake. Is KJ Boone an Anthropocene version of Ebenezer Scrooge? If so, Saunders has forgotten something fundamental about that Victorian wretch: we end up rooting for him. This was the stake of A Christmas Carol, and the source of its lasting and radical comfort. If Scrooge can change, maybe we can too.

Bon is different. He can’t undo the damage he’s done with a roasted turkey and a pay raise. He helped destroy the planet, so we watch him hoping – hoping – that he will be cursed in return. This is our protest.

We will meet his sarcastic daughter (“recovered from her brief flirtation incited with debauchery by her friend”); We will meet his wife, the cow. By the time Boone takes his last breath, we will have no doubt that he is what we think of him as: “the bully, the destroyer, the destroyer of the unrepentant world.” Retribution is an empty and terrible act, and this may be Saunders’ point. But there is little moral work to be done here: Boone has earned his fate (the arrogant one is likely to agree), and mercy is a special kind of punishment. Whatever Jill decides – whatever we decide – can be made to feel right.

It’s a waking fantasy: If only we could identify and eliminate the right institutional monsters, the ledger might balance. Billionaires and CEOs make excellent villains; Some even seem to enjoy the role. But cut one of them and a couple of others will sprout in its place; Economic hydra. This is true brutality. The climate crisis has no pathological opponent, because violence is structural, pervasive and horribly normal. Vigil spins around this idea, but it never escapes Boone’s appeal.

However, Jill “the doll” Blaine is the most interesting creature. In order to care for others – 343 charges so far – the death doula forgot herself: her past, her end, even her name. While Bon is dying, there is a wedding in progress next door, and the resulting joyful noise disturbs her cautious amnesia. Her own love story returns, but remembering it means reclaiming its ending. Somewhere in a secluded attic, a doula’s wedding dress is taking shape. How terrifying it is to feel lonely when forgotten. Much easier to do the forgetting yourself.

This is where Saunders’ ghosts do their most convincing work. Not as crude moral instruments, but as incomplete souls. Lincoln in the Bardo narrows history to one intimate catastrophe: Abraham Lincoln carrying the body of his dead son through a final long night. By staying with the specificity of loss—the weight of the boy in his father’s arms—the book made Lincoln more than just a great American allegory. He has been freed from symbolic duty and returned to the human world of love and loss. History was watching, but Saunders did not let him have the last word. The archival clippings he includes contradict each other. The only truth that remains is grief itself: private, indisputable, sufficient.

In Vigil, the spectral shenanigans begin to feel like gimmicks: polyphonic chatter, Beckettian riddles, and poo and fart jokes (Saunders loves a bawdy, gassy ghost, and a pile of imaginary excrement). What once seemed like chaos has become a habit; A repertoire of tricks and tics. They are used to teach us a lesson – and it is sad to fall for someone else’s morality play. Bardot Reader.

⚡ **What’s your take?**

Share your thoughts in the comments below!

#️⃣ **#George #Saunderss #Vigil #Review #worlddestroying #oil #tycoon #repent #imaginary**

🕒 **Posted on**: 1768982023

🌟 **Want more?** Click here for more info! 🌟