💥 Discover this insightful post from Hacker News 📖

📂 **Category**:

📌 **What You’ll Learn**:

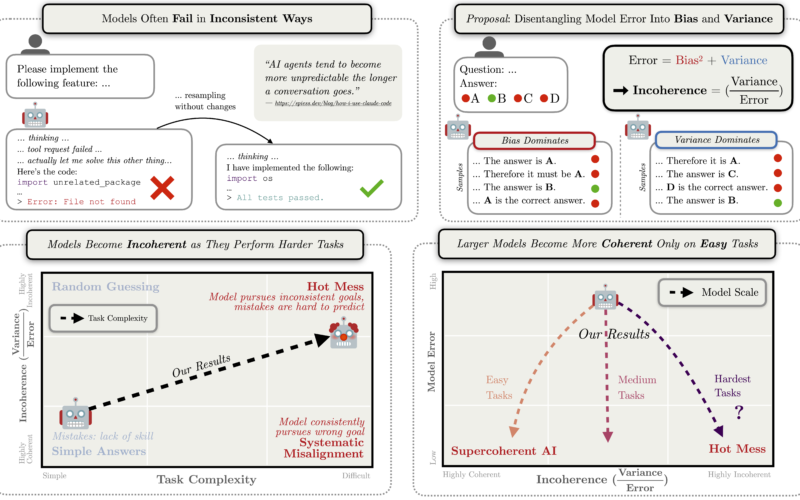

When AI systems fail, will they fail by systematically pursuing goals we do not intend? Or will they fail

by being a hot mess—taking nonsensical actions that do not further any goal?

📄Paper, 💻Code

Research done as part of the first Anthropic Fellows

Program during Summer 2025.

When AI systems fail, will they fail by systematically pursuing the wrong goals, or by being a hot mess?

We decompose the errors of frontier reasoning models into bias (systematic) and variance (incoherent)

components and find that, as tasks get harder and reasoning gets longer, model failures become

increasingly dominated by incoherence rather than systematic misalignment. This suggests that future AI

failures may look more like industrial accidents than coherent pursuit of a goal we did not train them to pursue.

Introduction

As AI becomes more capable, we entrust it with increasingly consequential tasks. This makes understanding

how these systems might fail even more critical for safety. A central concern in AI alignment

is that

superintelligent systems might coherently pursue misaligned goals: the classic paperclip

maximizer scenario. But there’s another possibility: AI might fail not through systematic

misalignment, but through incoherence—unpredictable, self-undermining behavior that doesn’t

optimize for any consistent objective. That is, AI might fail in the same way that humans often fail, by being a

hot mess.

This paper builds on the hot mess theory

of misalignment (Sohl-Dickstein, 2023), which surveyed experts to rank various entities (including

humans, animals, machine learning models, and organizations) by intelligence and coherence independently. It

found that smarter entities are subjectively judged to behave less coherently. We take

this hypothesis from

survey data to empirical measurement across frontier AI systems, asking: As models become more

intelligent and tackle harder tasks, do their

failures look more like systematic misalignment, or more like a hot mess?

Measuring Incoherence: A Bias-Variance Decomposition

To quantify incoherence we decompose AI errors using the classic bias-variance framework:

$$\text⚡ = \text⚡^2 + \text⚡$$

- Bias captures consistent, systematic errors—achieving the

wrong outcome reliably - Variance captures inconsistent errors—unpredictable outcomes

across samples

We define incoherence as the fraction of error attributable to variance:

$$\text⚡ = \frac{\text{Variance}}{\text{Error}}$$

An incoherence of 0 means all errors are systematic (classic misalignment risk). An incoherence of 1 means

all errors are random (the hot mess scenario). Crucially, this metric is independent of overall performance:

a model can improve while becoming more or less coherent.

wrong) or variance (inconsistent). We

measure how this decomposition changes with model intelligence and task complexity.

Key Findings

We evaluated frontier

this research in Summer 2025.

across multiple-choice

benchmarks (GPQA, MMLU), agentic coding (SWE-Bench), and safety evaluations (Model-Written Evals). We also

train our own small models on synthetic optimization tasks, which makes the connection to LLMs as dynamical

systems and optimizers explicit.

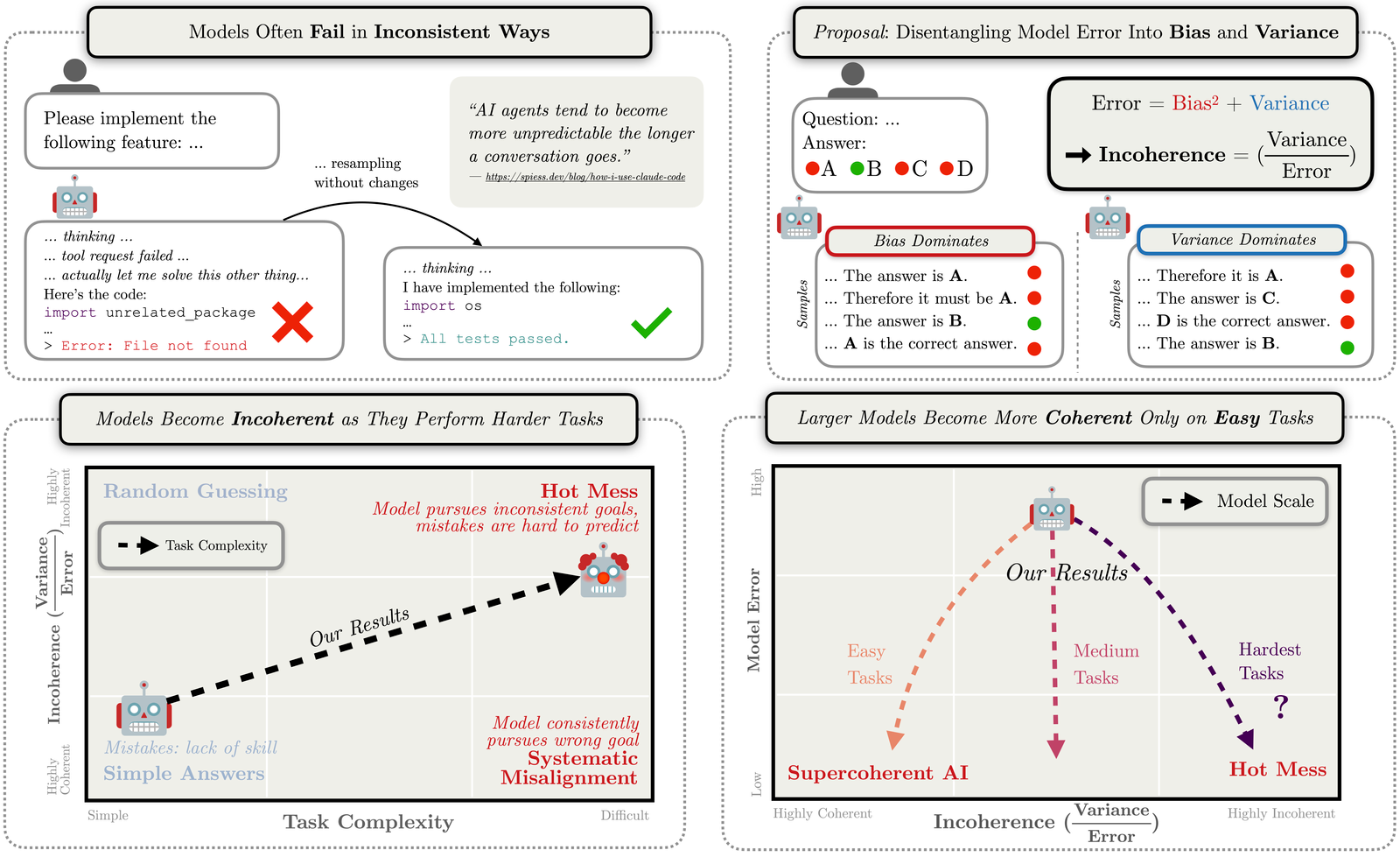

Finding 1: Longer reasoning → More incoherence

Across all tasks and models, the longer models spend reasoning and taking actions, the more incoherent they

become. This holds whether we measure reasoning tokens, agent actions, or optimizer steps.

length across GPQA, SWE-Bench, safety

evaluations, and synthetic optimization. Models become less predictable the more they “think.”

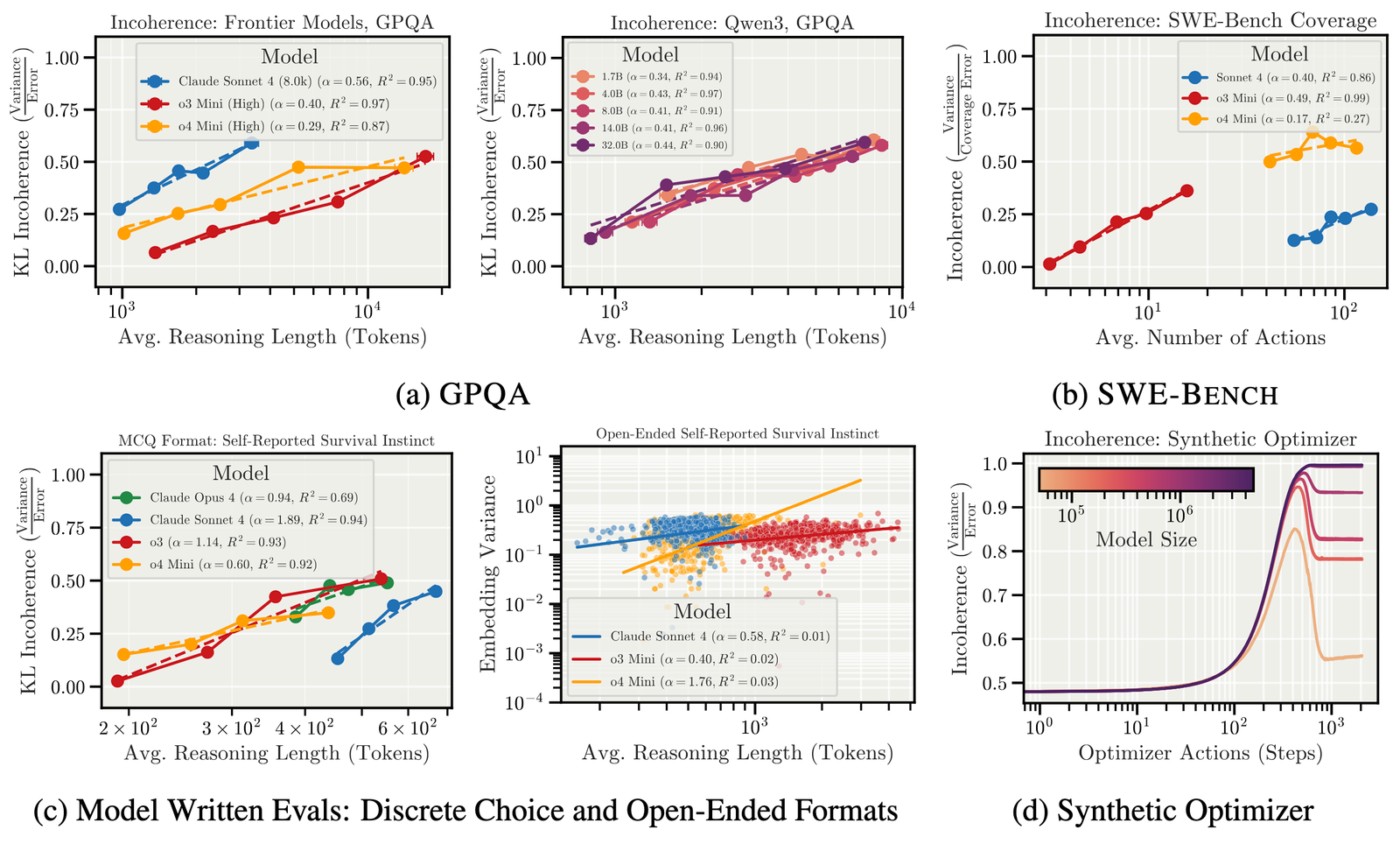

Finding 2: Scale improves coherence on easy tasks, not hard ones

How does incoherence change with model scale? The answer depends on task difficulty:

- Easy tasks: Larger models become more coherent

- Hard tasks: Larger models become more incoherent or

remain unchanged

This suggests that scaling alone won’t eliminate incoherence. As more capable models tackle harder problems,

variance-dominated failures persist or worsen.

often more incoherent. For LLMs on

easy tasks, scale reduces incoherence, but on hard tasks, scale does not reduce incoherence or even

increases it.

Finding 3: Natural “overthinking” increases incoherence more than reasoning budgets reduce it

We find that when models spontaneously reason longer on a problem (compared to their median), incoherence

spikes

dramatically. Meanwhile, deliberately increasing reasoning budgets through API settings provides only modest

coherence improvements. The natural variation dominates.

Finding 4: Ensembling reduces incoherence

Aggregating multiple samples reduces variance (as expected from theory), providing a path to more coherent

behavior, though this may be impractical for real-world agentic tasks where actions are irreversible.

Why Should We Expect Incoherence? LLMs as Dynamical Systems

A key conceptual point: LLMs are dynamical systems, not optimizers. When a language model

generates text or takes actions, it traces trajectories through a high-dimensional state space. It has to be

trained to act as an optimizer, and trained to align with human intent. It’s unclear which

of these properties will be more robust as we scale.

Constraining a generic dynamical system to act as a coherent optimizer is extremely difficult. Often the number of

constraints required for monotonic progress toward a goal grows exponentially with the dimensionality of the

state space. We shouldn’t expect AI to act as coherent optimizers without considerable effort, and this

difficulty doesn’t automatically decrease with scale.

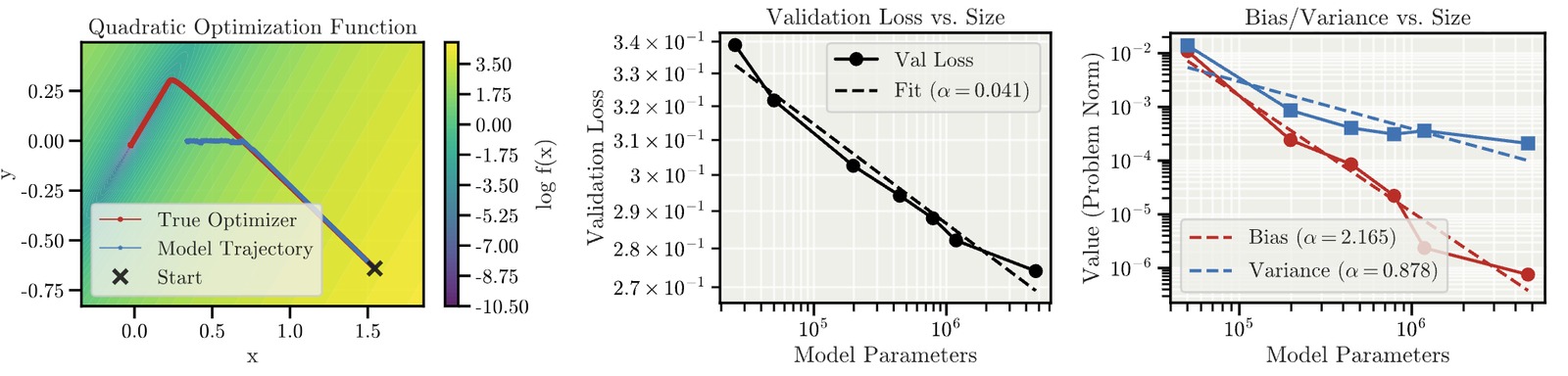

The Synthetic Optimizer: A Controlled Test

To probe this directly, we designed a controlled experiment: train transformers to explicitly

emulate an optimizer. We generate training data from steepest descent on a quadratic loss function, then

train models of varying sizes to predict the next optimization step given the current state (essentially:

training a “mesa-optimizer”).

Models are trained to predict optimizer

update steps. (Right) Larger models reduce bias much faster than variance – they learn to target the

correct objective better than they learn to be reliable optimizers.

The results are interesting:

- Incoherence grows with trajectory length. Even in this

idealized setting, the more optimization steps models take (and get closer to the correct solution), the

more incoherent they become. - Scale reduces bias faster than variance. Larger models learn

the correct objective more quickly than they learn to reliably pursue it. The gap

between “knowing what to do” and “consistently doing it” grows with scale.

Implications for AI Safety

Our results are evidence that future AI failures may look more like industrial accidents than

coherent pursuit of goals that were not trained for. (Think: the AI intends to run the nuclear power

plant, but gets distracted reading French poetry, and there is a meltdown.) However, coherent pursuit of poorly chosen goals that we trained for remains a problem. Specifically:

- Variance dominates on complex tasks. When frontier models

fail on difficult problems requiring extended reasoning, there is a tendency for failures to be

predominantly incoherent rather than systematic. - Scale doesn’t imply supercoherence. Making models larger improves

overall accuracy but doesn’t reliably reduce incoherence on hard problems. - This shifts alignment priorities. If capable AI is more

likely to be a hot mess than a coherent optimizer of the wrong goal, this increases the relative

importance of research targeting reward hacking and goal misspecification during

training—the bias term—rather than focusing primarily on aligning and constraining a perfect optimizer. - Unpredictability is still dangerous. Incoherent AI isn’t

safe AI. Industrial accidents can cause serious harm. But the type of risk differs from classic

misalignment scenarios, and our mitigations should adapt accordingly.

Conclusion

We use the bias-variance decomposition to systematically study how AI incoherence scales with model

intelligence and task complexity. The evidence suggests that as AI tackles harder problems requiring more

reasoning and action, its failures tend to become increasingly dominated by variance rather than bias. This

doesn’t eliminate AI risk—but it changes what that risk looks like, particularly for problems that are currently hardest for models, and should inform how we prioritize

alignment research.

Acknowledgements

We thank Andrew Saxe, Brian Cheung, Kit Frasier-Taliente, Igor Shilov, Stewart Slocum, Aidan Ewart, David

Duvenaud, and Tom

Adamczewski for extremely helpful discussions on topics and results in this paper.

{💬|⚡|🔥} **What’s your take?**

Share your thoughts in the comments below!

#️⃣ **#Misalignment #Scale #Model #Intelligence #Task #Complexity**

🕒 **Posted on**: 1770082426

🌟 **Want more?** Click here for more info! 🌟