✨ Explore this awesome post from Culture | The Guardian 📖

📂 **Category**: Theatre,Stage,Culture,Musicals,Entertainment TV,Television & radio

📌 **What You’ll Learn**:

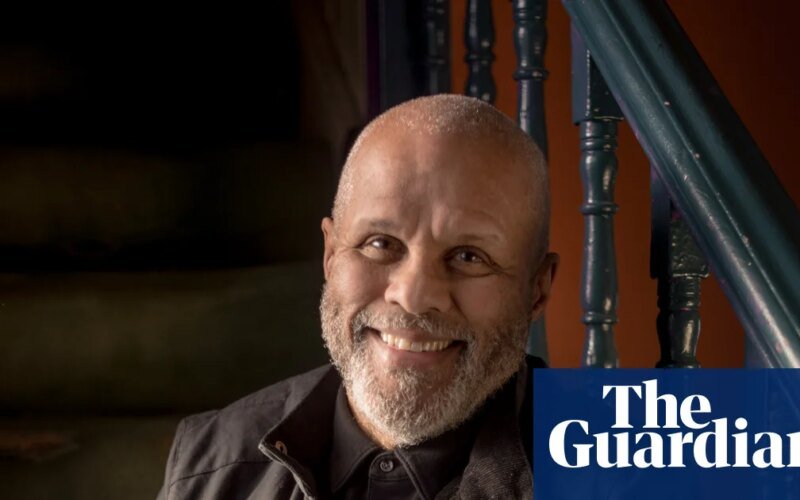

gAri Wilmot has lived many lives. Children’s TV presenter turned variety presenter, turned panto prodigy, turned musical sensation, Willmott has now turned his hand back to playwriting. His London debut is a comedy about two men waiting. One is cold and the other is disturbed. They both became enslaved by the waiting. Very Samuel Beckett, isn’t it? The two men could be Vladimir and Estragon, right?

“It’s funny you should say that,” says Wilmot, sitting upstairs at the Gatehouse Theatre, the theater above one of the London pubs of While They Waited, and in which he also stars, opposite Steve Forrest. Shortly after the play was commissioned, he was asked whether he had been influenced by Beckett’s existentialist play Waiting for Godot. He had never seen it before, but there happened to be a production in the West End starring Ben Whishaw and Lucian Msamati. Wilmot went and saw him and left in shock. “There’s a reason I’ve never seen this before,” I thought. “I have no idea what’s going on.”

This is a confession that not every actor dares to make. “Well, I’m honest about things,” he says, and it’s true – Wilmot is full of a refreshing honesty that feels like comic self-deprecation at times, perhaps with the intent to disarm and amuse. It’s instantly likable, measured in tone, and, at 71 years old, still carries a kind of enduring bounce.

“I sat in on a workshop for the musical Paddington a few years ago,” he says, following Beckett’s story. Is he referring to the theatrical juggernaut that currently exists in the West End? “Yes, it was being workshopped and I was playing [the equivalent of] Hugh Grant’s character from the movie. This character had been crippled… So at the end of the workshop, when we were sitting around talking with the producers and the director, I said, “I’m going to take myself out of the business here but why is my character in this?” It’s so disconnected from everything else.

He actually put himself out of the job, and that character disappeared from the script. Wilmot has no regrets. He says it’s about entertainment, not ego.

This slogan clearly worked for Wilmot, whose career spanned more than half a century. For a certain generation, he is a household name. He was a finalist on the reality TV competition New Faces in the late 1970s, and a presenter of endlessly active children’s shows in the 1980s such as So You Want to Be the Best? But younger generations, he points out without a hint of offence, have never heard of him.

However, he’s never been short of work, thanks to some clever tweaks to his skill set. When television shows became obsolete, he went into musical theatre, where he excelled as Cockney man Bill Snipson in Me and My Girl, and starred as Yale man Elisha J. Whitney in the Olivier Award-winning Anything Goes, among others. There’s a determination to Wilmot that sounds admirably old-school, a will to get out on the road, and push himself, no matter the size of the venue or crowd. He has written two plays before that were performed at his village hall in Tring in Hertfordshire, including one called The Horse which, he explains, is about a man who thinks he is a horse (he refrained from making comparisons with Peter Shaffer’s Equus after Beckett’s failure). So it seems like a quiet king of reinvention? No, he says, none of these twists were premeditated. “I wasn’t ambitious until about 10 years ago,” he says, but he’s a changeable person by nature: “I’ve always been someone who looks for new things.”

He left school when he was fifteen, barely able to read and write. It was a comprehensive school education [in south London] Which failed me comprehensively. I couldn’t wait to get out.” He didn’t think about the entertainment industry as a career for himself, even for a minute, but his friends did. “They thought I was funny, and they decided to push me, and one person in particular. It’s funny how some people come into your life for a short moment and impact it forever. He said he met a theatrical agent. He gave me his business card and said, “I told him you were great.”

Wilmot was 21 and worked as a scaffold and forklift driver. The agent put him in touch with an impressionist artist who gave lessons to young performers. For £5 an hour, he learned the basics and started playing. “I found something that everyone thought I was good at, so I kept doing it. But I think I knew from day one that it felt good to make people laugh. I remember being six years old dancing around, shaking my butt and doing a My Boy Lollipop imitation.”

As someone who started his career on a TV talent show, he believes the format at the time was first and foremost about finding new talent. “It seems to me now that it’s more about maintaining the image of the panelists rather than finding new talent that will last. If you asked someone who won the X Factor last year they wouldn’t have a clue, but 10 years later [Wilmot’s professional partner] “Jodi and I won New Faces, and people were like, ‘Oh, you’re the guy from New Faces.’”

Although he was given little legs, Wilmot had entertainment in his blood; His father was a professional singer in a group called Southlanders. The song they became famous for was “I’m a Mole and I Live in a Hole,” Wilmot says, singing it in baritone. “My dad was the bass.” Harry Wilmot, born and raised in Jamaica, came to Britain on the ship Empire Windrush in 1948, and fell in love with Wilmot’s white British mother. They would have been a very obvious anomaly as a mixed-race couple in post-war Britain.

“It was only when she had children that she realized how difficult it was for her,” he says. “She was a dancer, and her dance partner was her brother. When my father came, he completely and completely disowned her.” She died in 1978, just as Wilmot was on the verge of his television breakthrough. “She didn’t see new faces. It was nice to see her,” he says, his calm tone all the more poignant.

He speaks in the same gentle tone about his father, who died when Wilmot was seven years old. From his stories, it seems as if he was searching for it in adulthood. “One time, I was rehearsing a musical in south London and saw posters for the Windrush exhibition at the Imperial War Museum.” He went with him and watched footage of a BBC report from the deck of the Windrush, in which he recognized his father during the interview. “I said to a stranger: This is my father!”

Then there’s the famous Windrush photograph showing his father: “They’re two men standing and in the middle there’s a man sitting on a box. My father is the one in the middle. They’re all very elegant. I met one of the men recently in an exhibition at the British Library. He was in a wheelchair and I said to him: ‘I was in that picture with my father.’ What did he look like?” He told me he didn’t know him. The photographer said, ‘You, you, you, come here,’ and that’s what photographers do.”

Was Wilmot angry when the Windrush scandal broke? “No, I felt like everyone else. Any reasonable person would have said, ‘This guy is 60 years old, and he works in this country…’”

If Britain in the 1960s was hard on his mother, it wasn’t easy for him or his brother either. “We were two black boys in a white-dominated society with a white mother.” He also says there was a strong sense of neighborliness at his Lambeth property. “Everyone in my group was like that [called] Aunt or uncle. If I came home and my mother had a hospital appointment, Aunty Lou next door would say: “Come and have some tea with me.” This is what I did.

He and his brother met about 25 years ago with all the boys they grew up with on the farm, and 54 men attended, he says. “Not only did I know all 54 men, I knew their brothers and sisters, and I knew their parents. We were in the banquet room of a hotel and had a great time. There was still a sense of community, but of those 54 men, only one was living on the property. We were all encouraged to get out.”

What about racism when you were a kid? He answers: Everything he got, he gave back tenfold. “If a guy had acne, big ears, was skinny or short and attacked me, I would take him back.” Maybe that’s how his sense of humor developed, he thinks. But the first time he felt black affected him was when he started acting in theater in the 1990s, “when the color of your skin meant you couldn’t play certain roles.”

He pointed it out, he says. “When me and my girl walked in, I had no idea what a typical cockney character from the 1930s was. But I was more like him than any of the guys who had played that character before because I knew that character. I’m happy to say they recognized that in me and gave me the role.”

He feels that things may now have swung too much in the other direction. “If there are two actors auditioning for Martin Luther King and one of them looks like him, and when he reads the ‘I Have a Dream’ speech you think ‘he’s a strong contender’… but then a guy comes along and he’s a much better actor. Just because the first guy is black, doesn’t mean he understands what was going on with Martin Luther King and what America and the world was going through. So along comes the actor who really gets to the root of the character, and when he gives you that speech, you think ‘I never knew what that speech meant until he told me it.’

But the white actor was not subjected to racist abuse in the street. “No, but it touched you,” Wilmot says. Is talking about authenticity misleading? “I think there’s a certain amount of improvement going on, but in a funny way I’m very happy about it because it means black and brown performers are getting a chance to improve and work with the best.

“But the more important point is that this is not the real world. It is an artificial world, and it is up to us to make the public believe the lies we tell.”

🔥 **What’s your take?**

Share your thoughts in the comments below!

#️⃣ **#wasnt #ambitious #Gary #Willmott #talks #comedy #panto #musicals #Beckettstyle #play #stage**

🕒 **Posted on**: 1771283181

🌟 **Want more?** Click here for more info! 🌟