💥 Read this awesome post from Culture | The Guardian 📖

📂 Category: Design,Art and design,Culture,Exhibitions,Typography,New Order,Kraftwerk

📌 Main takeaway:

WWhen Otto Neurath died in Oxford nearly 80 years ago, far from his native Vienna, he was still finding his feet in exile. Like many Jewish refugees, the economist, philosopher and sociologist was interned as a suspected enemy alien on the Isle of Man, along with his third wife and close collaborator Marie Redmeister, after they made a last-minute escape for their lives from their temporary hideout in the Netherlands across the Channel in a rickety boat in 1940.

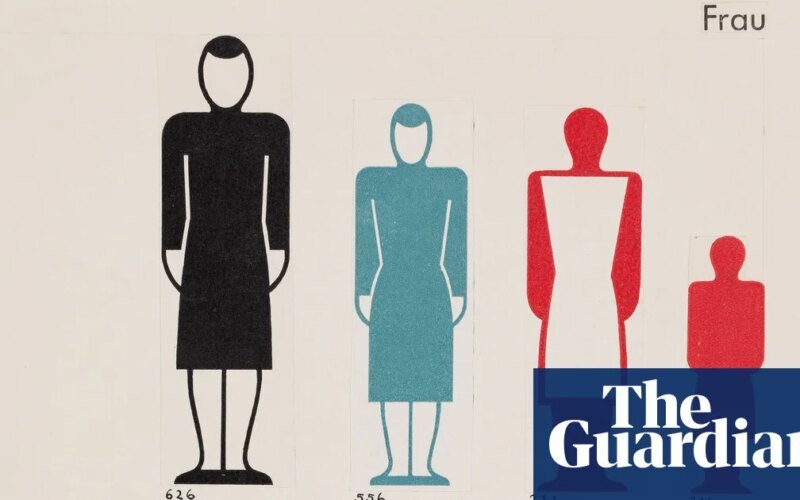

Thanks to Neurath’s pioneering use of pictorial statistics – or “homotypes,” as Ridemeister called them, an abbreviation for the International Typography Learning System – he left behind an enormous legacy in the arts and social sciences: the language through which we decode and analyze the modern world. But his lasting significance was difficult to predict at the time of his death at the age of 63.

At that point, the Viennese style of pictorial statistics had relatively little impact in the UK (except for providing strikingly simplistic images for informational short films by left-wing director Paul Rotha). Neurath’s “Visual Autobiography” was shelved by his publishers, who perhaps failed to follow the ambitious path of its title, “From Hieroglyphics to Homotype.”

Marking the civilizational pinnacle reached in his own book, this book – which remained unpublished until 2010 – outlined his democratic vision for a way to overcome educational class divisions, as crystallized in the slogan: “Words divide, images unite.”

This harkened back to the socialist ethos of the interwar ‘Red Vienna’, which was uncomfortable with the unashamedly profit-driven orientation of post-war Anglo-American capitalist popular culture. However, Neurath’s enthusiasm for modern methods of reproduction is consistent with the nature of pop music as mass-manufactured art with no unique origin. Just as advertising slogans or pop songs seek instant appeal, Neurath also called for images that “show the most important thing about the thing at first glance.”

In retrospect, his thoughtful semiotics anticipated much of Pop Art. Just as pop music follows hedonistic principles, Neurath’s goals went beyond utilitarianism. As one of the key elements of Vienna’s social housing program, he placed “happiness” above the practical advantages of classification and standardization, which infuriated purists by declaring that “the optimal technical solution in no way coincides with the greatest happiness.” At the same time, Neurath was fascinated by the new technology, championing fellow exile Walja’s Saraga generator—an early electronic instrument similar to a theremin but controlled by light—and predicting the creation of artificial “analog sound” for future documentaries.

It makes so much sense that in 2017, UK synthpop duo Orchestral Maneuvers in the Dark – who have harnessed the unexpected magic of synthesized speech since their 1983 album Dazzle Ships – will release a song called Isotype. The song was intended to celebrate Neurath’s “damn genius,” as their singer and lyricist Andy McCluskey said, speaking to me from his home on the Wirral. He and Peter Saville, the graphic designer who notably designed the aesthetics of early OMD albums as well as the corporate identity of Manchester label Factory Records (Joy Division, New Order, etc.) came across Neurath’s path in the early 1980s.

To them, the unadorned Isotype style – mostly designed by Neurath’s favorite artist Gerd Arntz – seemed to fully anticipate the graphic asceticism of the post-punk era. “We liked the idea of keeping things to a minimum and still getting the point across,” McCloskey says. “We grew up with Kraftwerk’s Autobahn album, which in its later guise was a simple model of a motorway sign with the two motorways and the bridge on a blue background. So those were the frames of reference going back decades.”

However, there is some contradiction in McCloskey’s admiration for Neurath’s primitive images. “What worried me was one of Otto Neurath’s phrases: ‘It is better to remember simple pictures than to forget exact numbers,’” he says. “Originally this would have been a slogan I would adore. But it’s also a scary indicator of the world we live in now, both in terms of sound bites and our limited ability to understand. Doesn’t that sound like Donald Trump’s entire political slogan?”

The OMD Neurath tribute video is a poignant mandala of isotopes created by German artist Henning M Lederer, and takes pride of place in Wissen für alle: Isotype (“Knowledge for All”), a newly opened exhibition on Neurath’s work and legacy at the Vienna Museum, Vienna’s recently beautifully expanded mid-century-style city museum on Karlsplatz, in the center of the Austrian capital.

Featuring many of the original yellow posters designed for ‘Museums of the Future’ that can be reproduced on a large scale at Neurath, it is a compact but effective display brimming with the utopian socialist energy that ran through the streets of Vienna in those heady days before the arrival of first Austrian Fascism, and then the Nazi regime. But what seemed like mere nostalgia a few years ago now seems like a rediscovered guide to resistance; It is a useful reminder of how left politics deals with the challenge of overcoming intellectual snobbery and striving to make itself understood.

🔥 Share your opinion below!

#️⃣ #Images #Unite #Pop #Music #Fell #Love #Socialist #Charts #design