🔥 Check out this must-read post from Culture | The Guardian 📖

📂 Category: Art,Folklore and mythology,Art and design,Culture,British identity and society,Social history,Depression,Society

📌 Here’s what you’ll learn:

A A little toy dog named Lunar arrives at Ben Edge’s studio door with excitement. There’s also a full-size fiberglass horse, already halfway through the door. She is ridden by a mannequin wearing a wreath of artificial flowers, underneath a shirt decorated with green men and Uffington White Horse and oak leaf references. It’s identical to the one worn by the living, breathing artist standing next to me.

A highlight of the upcoming EDGE exhibition at London’s Fitzrovia Abbey, the sculpture is titled ‘Where Should We Go in Search of Our Better Selves’. It is an unparalleled self-portrait, showcasing the remarkable traces of Renaissance chivalry, and honoring the Garland King, a figure from the recesses of British folklore, who every May strolls through the village of Castleton in Derbyshire. “Garland King has become an icon to me,” Edge says. “I see it as representing the process of finding your own nature, and turning inward.”

Ten years ago, Edge stumbled upon a druid party on Tower Hill, London. It turned out to be the spring equinox: “When I came out of the station, I saw in the distance this line of people in white gowns walking past a red telephone box, or a KFC, or a Wetherspoon. They gathered in a circle, and they started talking about the idea of reconnecting with nature, and that nature would one day take back London. They were putting seeds on the ground. It was a real awakening for me.”

Since then, Edge has become a leading light in the British folk renaissance. It is an artistic movement steeped in storytelling, crafts, and beliefs that sought to connect communities to nature. From Sailing in January to Morris Dancing at the Vernal Equinox, discovering and documenting such time-honored practices has saved Edge from chronic depression, and provides inspiration for works that combine poetic mysticism and social realism.

In a climate of far-right politics driven by what feels like a national identity crisis, Edge’s folkloric quest inevitably intersects with those mourning the death of Merry Old England. “There is a myth that our popular culture is in trouble,” he says. He adds that it is actually thriving. What has changed is that people are talking about it now.

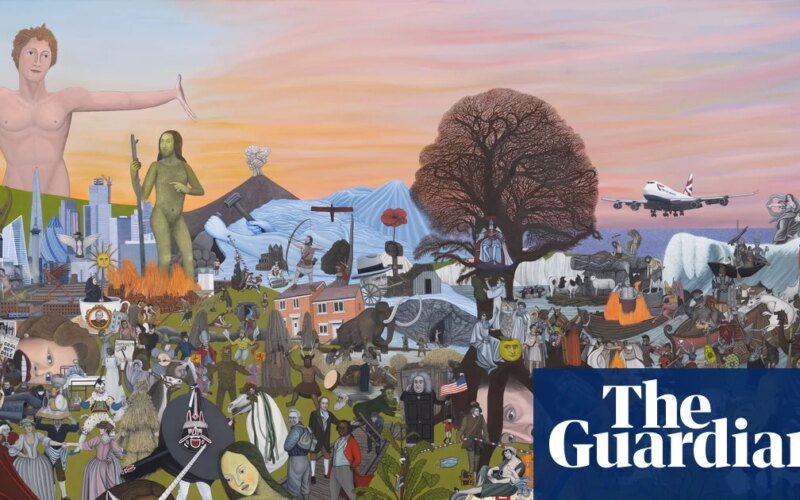

Children of Albion, the near-slaughter epic that gives the Edge exhibition its title, explores the richness of Britain’s history in fascinating detail. Combining the grotesque twists of Bush’s Garden of Earthly Delights with the surreal humor of Terry Gilliam, it is the culmination of a body of work that began after the dual crises of Brexit and the pandemic.

“In the post-Brexit era, we are all grappling with our identity as a country,” he says. “I had to draw the children of Albion because I needed to solve the whole puzzle.” The result is a visual survey of the people and events that shaped the British Isles, with refugees on boats, Stonehenge, Viking raids and a miners’ strike taking their places alongside Morris dancers and the slave trade.

The paper umbrella in this volatile cocktail of ingredients is ‘albion’, the ancient word for pre-Roman Britain. These days, it is more easily associated with white supremacy than the universal vision of humanity proposed by the Romantic poet and artist William Blake. But Edge, inspired by Blake, represents Albion as a benevolent figure, overseeing the massive oil painting like a rising sun. “In Blake’s personal mythology, Albion was a sleeping giant,” Edge explains. The painting shows his moment of awakening: “The idea is that this happens by accepting the truth of who we are as a nation and finding a way forward.”

If our patchwork of regional customs seems ill-equipped to bring tolerance and unity to our tense and fractured society, Edge disagrees, noting that folk traditions around the world are rooted in universal concerns—birth, death, and the changing seasons. He believes that reconnecting with ancient customs offers a radical strategy for addressing the crises of our time. “When I was really clinically depressed, I had no connection to nature,” he says. “I’ve been living in the city for 10 years and my only contact with the environment has been putting my recycling in the correct bin.” For him, restoring this fractured relationship with nature is the key to tackling the climate emergency.

He says the closures have been transformative. “Covid has fundamentally shifted people’s mindsets about Britain and the climate crisis – even the Black Lives Matter movement has come out of it. Obviously it was a huge tragedy, but people have had time to reflect. They started to love their immediate landscape and feel proud. It was probably a bit disorienting at first, because a lot of left-leaning people after Brexit felt they had almost had enough of the country.”

Edge points out our distorted relationship with nature in Plastic Flowers in Where Should We Go in Search of Our Better Selves?, But it’s also a nod to the people who make up folk traditions every year, improvising costumes and props with whatever comes to hand. His own process is similarly independent in spirit. “There is no gallery that will come and save you, you need to build your own art world,” he says. “The moment I had that realization, everything started going well for me.”

💬 Share your opinion below!

#️⃣ #painting #Identity #struggles #Sufi #artist #Ben #Edge #art