🔥 Explore this trending post from Culture | The Guardian 📖

📂 Category: Art,Painting,Sculpture,India,Royal Academy of Arts,Art and design,Culture,South and central Asia

✅ Here’s what you’ll learn:

AWhen you enter the galleries, you can’t avoid the dilapidated giant. Perhaps drunk or drugged, it rises and falls, a red and brown creature with a devilish face and a flabby stomach. If the rope suspending him from the ceiling broke, he would just be a pile of tarp on the floor.

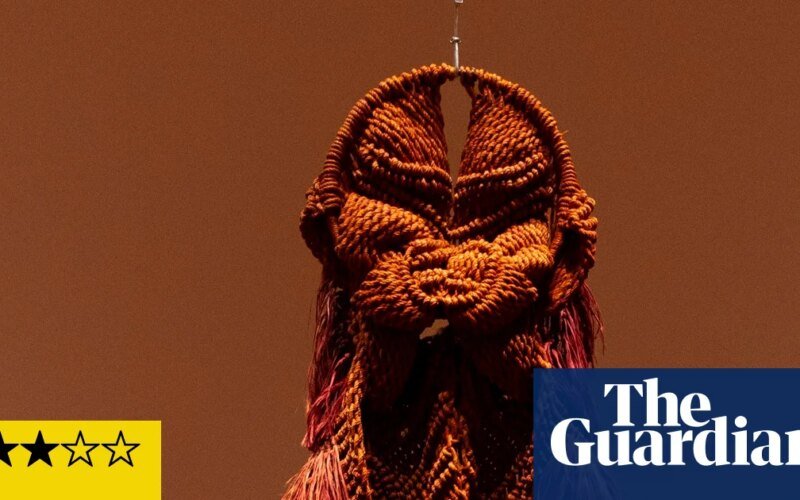

This monster has all the qualities that make the art of Mrinalini Mukherjee, who was born in Mumbai in 1949 and died in 2015, so funny, fascinating and surreal. She created it in 1985 and, like many of her works, made it from tightly woven, intensely colored natural fibres. It is called Bakshi, meaning bird, and now I see it, with its feathery sides and flexible wings. Mukherjee’s sculpture is a hallucinatory yet remarkable response to nature, full of echoes of the Indian landscape and, in this case, the Indian sky. If a bird can become the ogre of its imaginative imagination, a flower can grow into a fleshy, sprawling, bloodstained demise, and a tree turn to gold. So why is the Royal Academy trying to smother its delightful works in an incoherent display surrounding mediocre works by less interesting artists?

The big title is The Story of South Asian Art, but no story told here is interesting or even logical. A simple, traditional retrospective – an artist is born, their career begins, their work develops – will give you a nice linear framework but no, that would be too simple. Instead, this meandering “traces a century of South Asian art,” says the text on the wall at the entrance, placing Mukherjee within “a constellation of mentors, friends and family.” But why? Any gain is negligible compared to the loss of energy and urgency.

It starts out well enough. Mukherjee’s parents were artists and her father, Binod Bihari Mukherjee, had poor eyesight and eventually became blind. Maybe that’s why his Matisse-like collages are so electrically bright, and the colors so grainy and life-like. But if you want to follow the idea of exploring Mrinalini Mukherjee’s affiliations, it seems that she got her talent for sculpting from her mother Leela, whose carved wooden statues have great totemic energy.

Of course context is important, but why not dig deeper? Mrinalini Mukherjee’s sculpture has ancient and fascinating, and clearly self-conscious, roots in Indian art – or South Asian art as it is militant here – with its history of naturalistic surveillance, masked cobras, elephant-headed deities, dancing bodies and abstract freedom, and most mysteriously of the representation of Shiva as a cylindrical lingam. Mrinalini Mukherjee’s woven hemp sculpture ‘Adi Pushup II’ reminded me of the lingam, perhaps because they both draw inspiration from the stamen of the flower. This sculpture, whose title means “First Flower,” is a crudely shaped triangular plant that blooms with evocative overtones. She is consciously and intelligently rooted in the religions and arts of India and leaves all other artists in the deep shadow she casts.

This is the way things are. First, the inclusion of Mrinalini Mukherjee’s friends and family puts her early development in context. But once you see her sculptures from the 1980s onwards, you just want to see more of them and less, and soon nothing, of the watercolors through her “circle” clogging the gallery like slow-moving traffic. It’s as if she’s forced to have endless polite conversation about what everyone else is doing.

Her art is global, not local. Given her rise to glamor in the 1980s, it’s tempting to see her as a magical realist. It blends India’s modern history with surrealism, dreams and imaginative images of intense national landscapes. From this she produces an enchanted mixture of birds, flowers, gods and beasts filled with desire and awe. The Night Bloom II, owned by the British Museum, has the shape of a person sitting in a lotus position, yet it is another mind-festering flower, made of crude, slippery green ceramics, some of which are glazed blood-red.

The text on the wall says the figure appears feminine, but to me it evokes seated Buddhas and non-gendered sages. It is full of contrasts, both spiritual calm and sensual violence, and possesses a tension that makes a work of art not only impressive, but enduring.

Mrinalini Mukherjee’s art drew deeply on her culture but transcended the local culture. It is as meaningful now as it was in her life, and it is accessible to everyone. What’s so bad about that? Contemporary art hype is contemporary art hype – but no, this gallery keeps throwing a wet blanket over it. This is another landscape painting, another boring figurative screen.

How clever it is that the Royal Academy has put together a showcase for this great contemporary artist. How stupid it is to silence her in a second-rate environment. I think she knew exactly how much better she was than her family and friends.

⚡ Tell us your thoughts in comments!

#️⃣ #South #Asian #Art #Review #Story #Noisy #Sculpture #Marred #Depressing #Neighbors #art