✨ Explore this awesome post from Culture | The Guardian 📖

📂 Category: Best books of the year,Crime fiction,Thrillers,Culture,Books,Best books,Fiction

💡 Key idea:

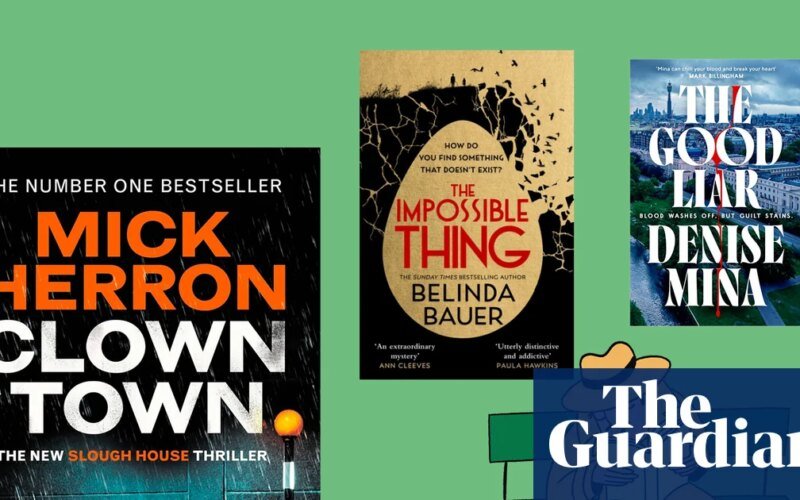

IIf we get the heroes we deserve, Jackson Lamb, the foul-mouthed, foul-mouthed ringmaster of the failed spy circus, is truly the man for our times. With Clown Town (Baskerville), the ninth book in Mick Herron’s satire/thriller mash-up series, hitting the bestseller lists, and the fifth series of TV adaptations of Slow Horses, this has been the author’s year. In their latest outing, Lamb and his team of “losers, misfits and alcoholics” hit the ground running as secrets regarding an IRA double agent threaten to come to light, exposing the bad side of state security to a tale of loyalty and betrayal.

Complicity and guilt, as well as class and professional morality, are the themes of Dennis Mina’s novel The Good Liar (Harvill). When the creator of a revolutionary blood spatter probability scale realizes that its flaws may have led to an unsafe conviction, she must decide what to do about it. Tense and powerful, this book is a sobering reminder of how the human element can undermine an apparently objective scientific method. Confessions of Paul Bradley Carr (Faber) ventures into similar territory to terrifying effect. It takes place in a very plausible future where the world has become dependent on algorithmic decision-making; Things go disastrously wrong when the AI begins to regret some of its decisions, leading to carnage.

Equally important, though for different reasons, is French author Olivier Norick’s surprising book The Winter Warriors (Open Borders, translated by Nick Caestor), which tells the true story of the Soviet Union’s 1939 invasion of Finland and the astonishing exploits of Simo Haiha, a Finnish sniper so effective that Stalin’s fearsome forces nicknamed him “The White Death.” The second book in Joseph O’Connor’s Rome Escape Line trilogy is another remarkable testament to humanity’s courage and resilience. Continuing the story of resistance fighters in Nazi-occupied Italy, The Ghosts of Rome (Harvill) is every bit as poignant and immersive as its predecessor, My Father’s House.

Northern Irish writer Eoin McNamee is best known for his literary reimaginings of true crime, but in The Bureau (Riverrun) he uses a family’s experience running a bureau de change near the Irish border as the starting point for his 1980s black market tale, set against a backdrop of political violence and focusing on the doomed relationship between a married gangster and his young mistress. Time, place, perverted morality, and masculinity are powerfully evoked in beautiful prose.

Abigail Dean’s third novel, Our Death (Hemlock), examines the effect of crime—in this case a violent home invasion, leading to rape—on a marriage. Twenty-five years later, the perpetrator, who had committed a series of similar crimes, some of which ended in murder, was arrested and put on trial, with the now divorced Edward and Isabel making statements of their influence. Dean weaves their perspectives, past and present, into an extraordinary psychological thriller that is also a love story, focusing on the years before and after the terrible event, exposing the fault lines in their relationship.

Belinda Power brings back Patrick Forte, the hero of Rubernecker’s 2013 novel, in The Impossible Thing (Bantam), a story set in the obsessive (and now illegal) world of bird egg collectors. Switching between 1920s Yorkshire, when Seeley Shepherd reverses her impoverished family’s fortunes by stealing a rare red egg from a guillemot, and the 21st century, when Patrick tries to track down a thief who has stolen an “old egg” in a vanity box from his neighbour, this funny, poignant and unexpected novel is a delight.

The relaxed, straightforward crime novel remains popular, but some authors borrow its tropes and conventions to explore different themes. Louise Hegarty’s feature debut, Fair Play (Picador), is the perfect example of this. It begins conventionally enough with a murder mystery-themed house party, during which a real death occurs. The rug is then sharply and repeatedly pulled from under the reader’s feet as two stories emerge: one is a Golden Age metafiction, full of side knowledge and sneaky fun; The other is a painfully realistic account from the point of view of the victim’s sister, alone and confused by grief. The result is a brilliant look at how we understand life and death.

Japanese YouTuber Uketsu, whose real identity is unknown (he wears a papier-mache mask), is responsible for what must be the most particularly disturbing crime novel of the year. Strange pictures (Pushkin Vertigo, translated by Jim Ryun) is a series of interconnected mysteries with visual and narrative clues, beginning with the chilling artwork of an 11-year-old girl arrested for maternal murder. It is encouraging to see that the genre remains as versatile and dynamic as ever.

⚡ Tell us your thoughts in comments!

#️⃣ #crime #thriller #films #books #year