🚀 Discover this must-read post from Hacker News 📖

📂 **Category**:

📌 **What You’ll Learn**:

A long, long time ago

I can still remember how a protocol

used to make me smile

And I knew if I had my chance

That I could make those botnets dance

And maybe they'd be happy for a while

But January made me shiver

With every packet I tried to deliver

Bad news on the backbone

I couldn't scan a single ASN

I can't remember if I cried

When my -f root hit an ACL line

But something touched me deep inside

The day the telnet died

So bye, bye mass spreading Mirai

Drove my SYNs down on the fiber line

But the fiber line was dry

And good old bots were passing creds in the clear and dry

Singin' this'll be the day that I die

This'll be the day that I dieOn January 14, 2026, at approximately 21:00 UTC, something changed in the internet’s plumbing. The GreyNoise Global Observation Grid recorded a sudden, sustained collapse in global telnet traffic — not a gradual decline, not scanner attrition, not a data pipeline problem, but a step function. One hour, ~74,000 sessions. The next, ~22,000. By the following hour, we were down to ~11,000 and the floor held.

Six days later, on January 20, the security advisory for CVE-2026-24061 hit oss-security. By January 26, CISA had added it to the KEV catalog.

We wrote about the first 18 hours of exploitation activity back on January 22. This post is about something different: the structural change in global telnet traffic that preceded the CVE, and why we think the two events may not be independent.

The Drop

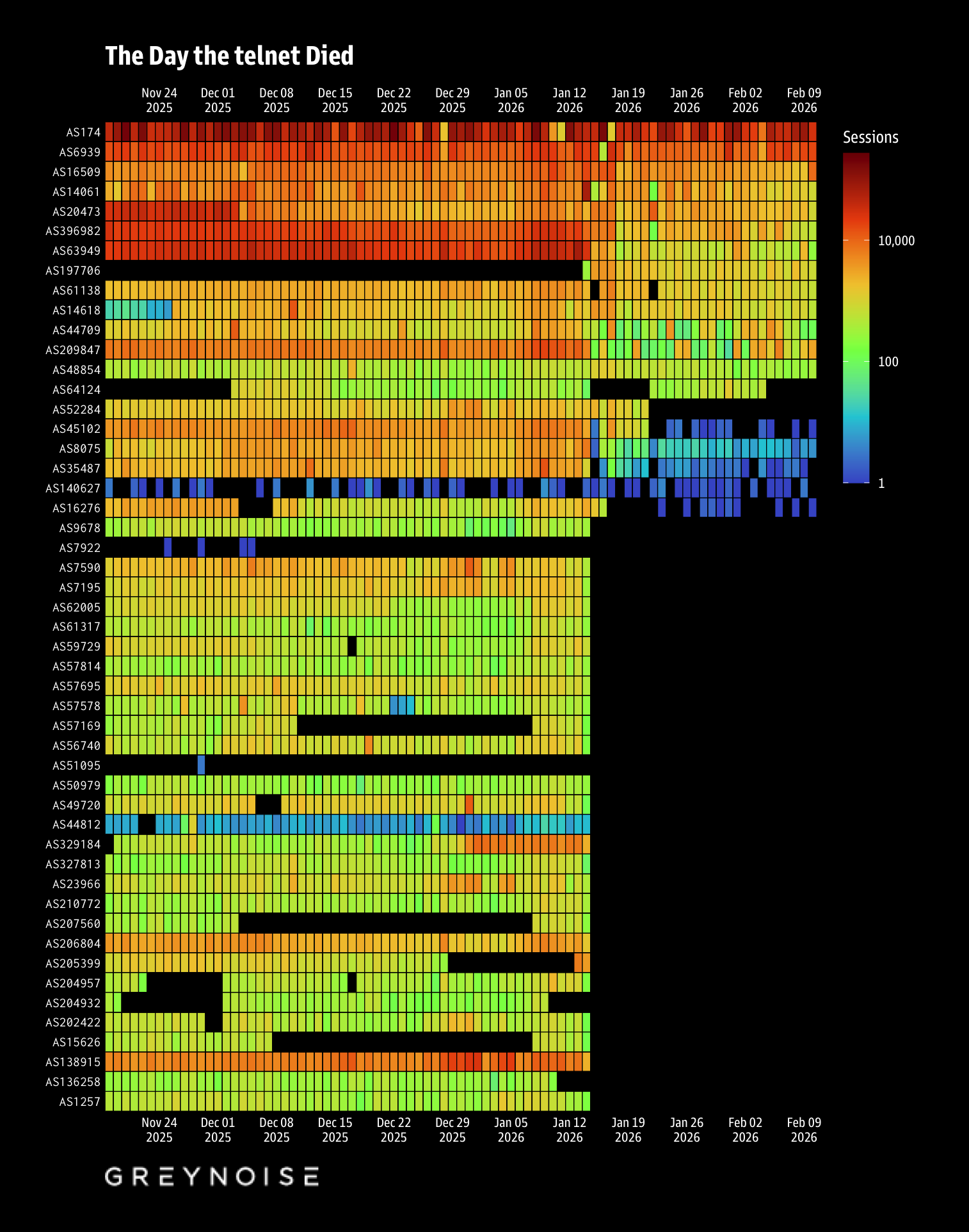

From December 1, 2025 through January 14, 2026, GreyNoise observed an average of ~914,000 non-spoofable telnet sessions per day across 51.2 million total sessions — let’s call that the “baseline”.

On January 14 at 21:00 UTC, hourly volume dropped 65% in a single tick. Within two hours it had fallen 83% below baseline. The new average settled around ~373,000 sessions/day — a 59% sustained reduction that persists through the time of writing (February 10).

This wasn’t a taper. The hourly data around the inflection point tells the story:

| Jan 14, 19:00 | 73,900 | Normal baseline |

| Jan 14, 20:00 | 64,722 | Normal baseline |

| Jan 14, 21:00 | 22,460 | 65% drop in one hour |

| Jan 14, 22:00 | 11,325 | 83% below baseline |

| Jan 14, 23:00 | 11,147 | New floor established |

| Jan 15, 00:00 | 12,089 | Sustained at reduced level |

That kind of step function — propagating within a single hour window — reads as a configuration change on routing infrastructure, not behavioral drift in scanning populations.

What Went Silent

Eighteen ASNs with significant pre-drop telnet volume (>50K sessions each) went to absolute zero after January 15. Some of the names that stand out:

- Vultr (AS20473) — 382K pre-drop sessions, then nothing

- Cox Communications (AS22773) — 150K sessions, gone

- Charter/Spectrum (AS20115) — 141K sessions, gone

- BT/British Telecom (AS2856) — 127K sessions, gone

Five entire countries vanished from GreyNoise telnet data: Zimbabwe, Ukraine, Canada, Poland, and Egypt. Not reduced — zero.

Meanwhile, the major cloud providers were largely unaffected or even increased. AWS went up 78%. Contabo up 90%. DigitalOcean essentially flat at +3%. Cloud providers have extensive private peering at major IXPs that bypasses traditional transit backbone paths. Residential and enterprise ISPs typically don’t.

Where’s the Filter?

The pattern points toward one or more North American Tier 1 transit providers implementing port 23 filtering:

The timing — 21:00 UTC, which is 16:00 EST — is consistent with a US-based maintenance window. US residential ISPs (Cox, Charter, Comcast at -74%) were devastated while cloud providers on the same continent peered around whatever changed. Verizon/UUNET (AS701) dropped 79%, and as a major Tier 1 backbone, that’s consistent with it either being the filtering entity or sitting directly upstream of one. The 21% residual traffic on AS701 would represent paths that don’t transit the filtered links.

Countries that rely on transatlantic or transpacific backbone routes to reach US-hosted infrastructure got hit hardest. Countries with strong direct European peering (France at +18%, Germany at -1%) were essentially unaffected.

The Chinese backbone providers (China Telecom and China Unicom) both dropped ~59%, uniformly. That uniformity suggests the filter sits on the US side of transpacific links rather than within China. If this were a Chinese firewall action, we’d expect asymmetric impact across Chinese carriers and a harder cutoff.

Then Came the CVE

CVE-2026-24061 is a critical (CVSS 9.8) authentication bypass in GNU Inetutils telnetd. The flaw is an argument injection in how telnetd handles the USER environment variable during telnet option negotiation. An attacker sends -f root as the username value, and login(1) obediently skips authentication, handing over a root shell. No credentials required. No user interaction. The vulnerable code was introduced in a 2015 commit and sat undiscovered for nearly 11 years.

The timeline:

| Jan 14, 21:00 UTC | Telnet backbone drop begins |

| Jan 20 | CVE-2026-24061 advisory posted to oss-security |

| Jan 21 | NVD entry published; GreyNoise tag deployed; first exploitation observed |

| Jan 22 | GreyNoise Grimoire post on initial 18 hours of exploitation |

| Jan 26 | CISA adds CVE-2026-24061 to KEV catalog |

The six-day gap between the telnet drop and the public CVE disclosure is the interesting part. On its face, the drop can’t have been caused by the CVE disclosure, because the drop happened first. But “caused by” isn’t the only relationship worth considering.

The Supposition

Responsible disclosure timelines don’t start at publication. The researcher who found this (credited as Kyu Neushwaistein / Carlos Cortes Alvarez) reported the flaw on January 19, per public sources. But the coordination that leads to patches being ready, advisories being drafted, and CISA being prepared to add something to the KEV within six days of publication typically starts earlier than the day before disclosure.

Here’s what we think may have happened: advance notification of a trivially exploitable, unauthenticated root-access vulnerability affecting telnet daemons reached parties with the ability to act on it at the infrastructure level. A backbone or transit provider — possibly responding to a coordinated request, possibly acting on their own assessment — implemented port 23 filtering on transit links. The filtering went live on January 14. The public disclosure followed on January 20.

This would explain:

- The timing gap (advance notification → infrastructure response → public disclosure)

- The specificity of the filtering (port 23/TCP, not a general routing change)

- The topology of impact (transit-dependent paths affected, direct-peering paths not)

- The sustained nature (the filter is still in place weeks later)

We can’t prove this. The backbone drop could be entirely coincidental — ISPs have been slowly moving toward filtering legacy insecure protocols for years (ref: Wannacry), and January 14 could simply have been when someone’s change control ticket finally got executed. Correlation, temporal proximity, and a plausible mechanism absolutely do not equal causation.

But the combination of a Tier 1 backbone implementing what appears to be port 23 filtering, followed six days later by the disclosure of a trivially exploitable root-access telnet vulnerability, followed four days after that by a CISA KEV listing, is worth documenting and considering.

What the Post-Drop World Looks Like

The telnet landscape after January 14 shows a recurring sawtooth pattern — periodic spikes followed by troughs (e.g., January 28 at 806K sessions, then January 30 at 191K). This could indicate intermittent filter application, routing flaps around the filtering infrastructure, or scanner campaigns that happen to use paths not affected by the filter.

The weekly averages tell the sustained story:

| Dec 01 | 1,086,744 | 119% |

| Jan 05 | 985,699 | 108% |

| Jan 19 | 363,184 | 40% |

| Jan 26 | 407,182 | 45% |

| Feb 02 | 322,606 | 35% |

We’re now operating at roughly a third of the pre-drop baseline, and the trend is still slightly downward.

Practical Implications

If you’re running GNU Inetutils telnetd anywhere — and given the 11-year window, there are plenty of embedded systems, network appliances, and legacy Linux installations where it’s still likely present — patch to version 2.7-2 or later, or disable the service entirely. The CISA KEV remediation deadline for federal agencies is February 16, 2026. As noted, GreyNoise observed exploitation attempts within hours of disclosure and the campaign peaked at ~2,600 sessions/day in early February before tapering off.

If you’re a network operator and you haven’t already filtered port 23 at your border, the backbone-level filtering we’ve documented here suggests the industry is moving in that direction regardless. Someone upstream of a significant chunk of the internet’s transit infrastructure apparently decided telnet traffic isn’t worth carrying anymore. That’s probably the right call.

If you know anything about this (or was the brave soul who implemented it), drop us a line at research@greynoise.io.

💬 **What’s your take?**

Share your thoughts in the comments below!

#️⃣ **#Day #telnet #Died #GreyNoise #Labs**

🕒 **Posted on**: 1770768385

🌟 **Want more?** Click here for more info! 🌟