🔥 Explore this awesome post from Culture | The Guardian 📖

📂 **Category**: Art and design,Culture,Art,Exhibitions,Painting

📌 **What You’ll Learn**:

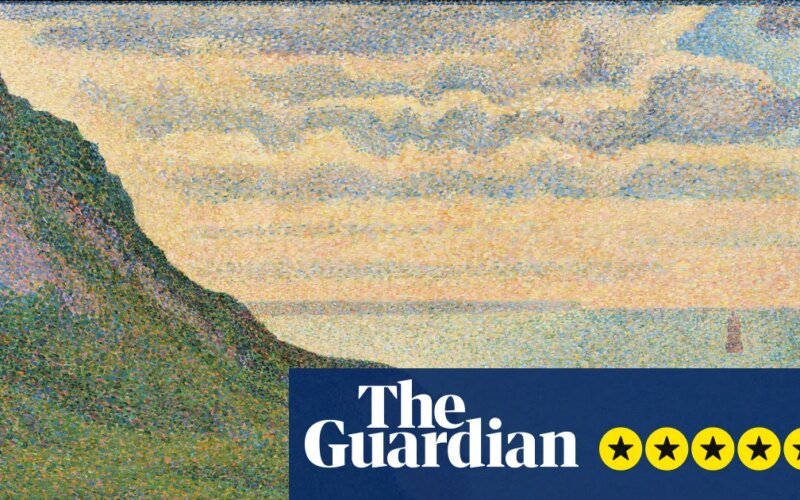

gGeorge Seurat died young. His two most famous paintings, both very large and innovative in their composition and technique, were completed while he was still in his mid-twenties. As it stands, Seurat painted approximately 45 paintings before his death, possibly of diphtheria, in March 1891 when he was 31 years old. More than half of these works depict the Channel coast and sea and were completed on his summer trips between 1885 and 1890. Seurat and the Sea at the Courtauld is the first exhibition devoted entirely to these images. Twenty-three paintings, smaller oil studies, and three drawings hang in two rooms. It’s a quietly enormous exhibition.

Even if we take into account the artist’s claims to science and objectivity and his adherence to theories about color and perception that distance him from Impressionism, Seurat’s paintings are strange and strange. Sometimes his line is very strange and harsh, and yet his drawings themselves – the tonal studies done with Conte crayon on textured and stretched paper, are among the most exquisite drawings I can think of. Surratt clearly knew what he was doing; Who knows what he could have gone on to achieve?

Despite his commitment to the juxtaposition of discrete dots and strokes of pure color rather than mixed pigments, so that the human eye could register transitional colors and that the surfaces of his paintings would retain a natural sheen, Seurat sometimes went to extremes with the dots he added to paintings often years after the original compositions were completed (which to my eye add little). These strongly colored and often dark painted frames, created and painted by the artist, are now discarded and mostly lost.

As for what has come to be called Seurat’s pointillism, his small, accumulated strokes and blisters of pigment, which make one aware of the effort and skill of his technique, you sometimes feel a kind of veil of interference between you and the image. In his small studies, usually painted on small wood panels, the size of his marks makes each individual touch significant – both in terms of tonality and color value – in the construction of the image. In Seurat’s larger paintings, when the artist makes his way across an undifferentiated expanse of sandy beach, the grass on the top of a cliff, or the stagnant waters of a harbour, all this strenuous effort can feel ponderous.

But when it all comes together, as it often does, that work turns into something else, and Seurat’s largely empty and uninhabited everyday scenes take on a quivering psychological sense of significance. Real or not, you feel his fixation and his gaze. Something is happening outside on the sunny day, the light hitting the harbor wall and sparkling on the calm water, the boat outside, the water stretching away to meet the sky, the bulkhead next to the wall, the posts and other bits of metalwork beside the working dock: it’s all happening everywhere at once, but it all takes time to register.

There is also a great deal of enjoyment to be found in the anomalies and sometimes baffling decisions that Seurat makes. He could be as volatile as he was analytical. The blue sky on one side of The Lighthouse at Honfleur is less saturated than on the other side. The view of the Grandcamp regatta is interrupted by a wonderfully untidy and lush patch of bush, creating a nice foil to the orange jib on the boat entering the panel on its left. These are the kinds of intentional accidents someone might do to please another painter. Seurat worked with the given and played with it. But he was keen to paint the shimmering brightness of the Channel coast on fine days when the weather didn’t change and the sea and sky became leaden. In those days, I think he stayed at home and worked on his still unfinished drawings and paintings.

The new sign on the cliff bridge at Port-en-Bessin is located in the upper left corner of the painting, almost out of sight, so that the eye almost struggles to find it. The complete series of six paintings by Seurat, completed at Port-en-Bessin, north of Bayeux, in the summer of 1888, have been bought back together for the first time since an exhibition in Brussels the following year. One feels the artist walking around the small town alone, observing things. French pennants and flags flap violently from the masts of boats anchored in the inner harbour, while the waters themselves are completely calm. A few stick-like figures cross a bridge in the distance. Another view, from the other side of the bridge, shows three people in the foreground, a man walking with his head down, a woman carrying a basket, and a young child alone and hunched over like a mannequin. Other loners loiter in the distance, as casually as they are laid out. There is an air of imminence, of something about to happen. In another painting, we are on the cliff, observing the same scene from another point of view, and in another, we turn to watch sailing boats pass between beautiful oval-shaped pools of shadow cast on the water by small clouds that we cannot see.

All the time I think of Seurat, the other recluse, with his portable paint box in hand, and a small canvas, on which he paints the scene, pinned to its lid. You think of him painting light, but he’s also interested in terrain, the shapes of objects, columns and lampposts, the new bridge, the fish market with its cast-iron columns. Two summers later, in 1890, the artist was in Gravelines, a flat coastal area between Calais and Dunkirk. Even now, his paintings tingle and explode with his little painted dots. The light of the North Sea is milky, slightly retreating from the summers in the south. A boat moves down the canal in the evening. There is no one in this violet hour, when the sun has set, only the man in the boat, and, I believe, the painter who follows its progress.

Seurat’s paintings are full of things – light, colour, objects, atmosphere and sense of place, but what he has most is the wonderful feeling of emptiness. It is present in the exhaustion of swimmers at the National Gallery at Asnières (1884), and in the crowded styles of Sunday at La Grande Jatte (1884-6) as much as in the seascapes. Sometimes I think I’m watching Seurat’s paintings as much as I’m looking at them, weaving through them, unseen and unnoticed, among his blizzards.

🔥 **What’s your take?**

Share your thoughts in the comments below!

#️⃣ **#God #Small #Surah #Sea #Review #Art #design**

🕒 **Posted on**: 1770856453

🌟 **Want more?** Click here for more info! 🌟