🚀 Explore this must-read post from Culture | The Guardian 📖

📂 **Category**: Books,Music,Stage,Culture,NFL,Race,Black US culture,Communism

💡 **What You’ll Learn**:

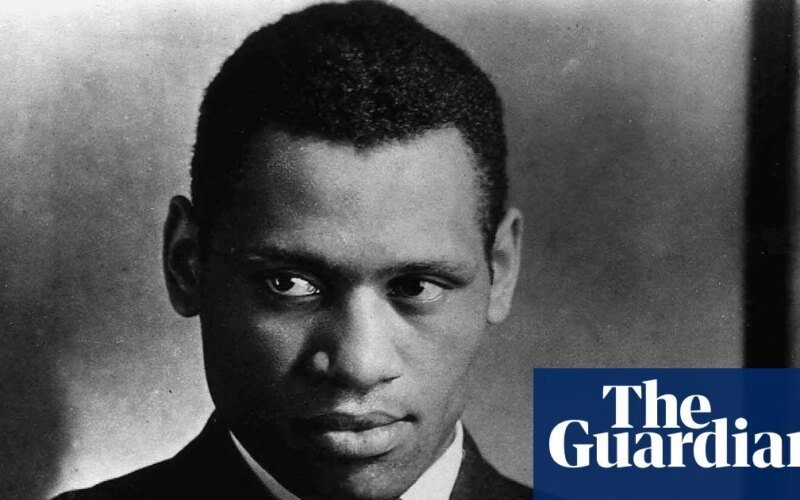

IIn August 1972, the front page of the New York Times Arts section ran a story with the headline: “Is it Time to Break the Silence on Paul Robeson?” The legendary bass-baritone spent the first half of the 20th century as one of the greatest talents the United States has ever produced, and the second half, both in life and in death as an outcast, the greatest victim of the Second Red Scare period to which current attacks on liberal and progressive politics are often compared.

This week marks 50 years since Robson’s death and the silence remains. His erasure from the lineage over the decades shows that what Robson’s political opponents did not take from him, the years have certainly taken from him. Robeson’s break from the story of African American culture was so complete that in the half-century since his death, generations of black Americans have never even heard of him.

His talent was amazing. Robeson joined Broadway in 1943, the first black man to play Othello in the United States. Previous productions of Shakespeare’s Jealous Moore cast white actors in blackface, and Robeson’s 296-performance run of Othello remains a Broadway record for a Shakespeare production. He was a two-time All-American at Rutgers, and one of the greatest college football players in history. He graduated from Columbia Law School, and before becoming world-famous as a musician, theater singer and actor in Hollywood, Robson played defensive tackle for two years in the National Football League. Robeson’s legacy has produced an astonishing roster of black theater artists, from Lena Horne to Harry Belafonte, James Earl Jones, Andre Braugher, Keith David, and Denzel Washington. At his peak, Paul Robeson was the most famous black American in the world.

However, because of his refusal to condemn the Soviet Union as Cold War tensions increased, Robeson was alienated by both the white mainstream and respected pillars of the black establishment—the NAACP, the Urban League and many leading black political and cultural voices who feared being labeled a communist by the rising tide of conservatism. Driven by what he called a sense of responsibility to prove that black Americans were loyal Americans, Jackie Robinson, the Brooklyn Dodgers star who two years earlier had integrated the white major leagues, was hailed as a national hero in 1949 for testifying against him before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Following Robinson’s testimony, bloody riots broke out protesting Robeson’s appearances at concerts in Peekskill, New York, and the combined pressure of national opinion and the federal government, effectively ending Robeson’s celebrity status. Robeson’s name has been removed from record books and historical texts, even those at Rutgers University, the alma mater that made him famous. Referring to him as “the most dangerous man in America,” the State Department refused to issue Robeson a passport for nearly a decade until the Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional to deny a citizen’s right to travel because of his political beliefs.

Robinson’s testimony and its influence on Robeson evoke parallels with the violent politics of today, where the citizenship of many Americans is questioned and threatened. Frustrated Black Americans are debating whether Donald Trump’s re-election, his subsequent assault on diversity initiatives — which last spring included removing a tribute to Jackie Robinson’s military service as part of its removal of DEI content (until an angry public backlash forced a reversal of the decision) — and racist rhetoric from Trump and members of his administration are evidence enough for disengagement, especially since another byproduct of today’s reality is an intensified period of hostility toward teaching Black people history and literature in public schools. As many progressives and liberals at the time implored Robinson not to testify against Robeson, this current moment of dark politics, the argument goes, is not our fight.

Robinson will never escape the part that contributed to Robson’s downfall – and he will feel his own sense of betrayal. Years later, at the height of the Vietnam War, the July 4, 1969, issue of The Times ran a front-page story about Americans living in a different time of division, and turned to Robinson, an enduring American hero, for his thoughts. By then, Jackie Robinson was embittered – by the lack of sustained racial progress in baseball, by a hard-line Republican Party whose hostility to civil rights led him to conflict and ultimately ended his loyalty to it, and by the inflexibility of the “love it or leave it” principle that had partly motivated him to testify against Robeson two decades earlier. The headline read: Science on July 4: A thrill for some, a threat for others. Reporter John Nordheimer chose Robinson, an Army veteran, to hit the leadoff spot. “I will not fly the flag on the Fourth of July or any other day,” former baseball star Jackie Robinson said. “When I see a car with a flag on it, I think the man driving it is not my friend.”

Those who sided with Robson saw no need for rediscovery because their faith in him never waned. The tallest tree in the forest. The great pioneer. cosmopolitan. He shaded those with his commitment and values, and in return received their protection, gratitude, and reverence. Along with many other letters in memory of Robeson, one letter to the editor, in particular, has emerged as an indictment of the community and individuals who now understand, with hindsight, the true scope of Robeson and, as Jackie Robinson described it when recalling his role in Robeson’s downfall, “the destruction of America.”

As one letter to the editor after Robson’s death says: “He is not mentioned in history books, like Nathan Hale. He is not mentioned in football broadcasts, like Red Grange. He is not mentioned in dramatic reviews, like Barrymore. He is not mentioned by opera critics, like Caruso. A man who was never mentioned despite the fact that he truly excelled not in one of the above fields, but in all of them. Now that the flames that burned in him have subsided he is laid dead on the floor, We remember and accept the fact that he lived. Now, safely silenced, he is suddenly mentioned as a “great American,” newspapers write editorials about him, halls of fame and history books will soon find a place for him, and we can congratulate ourselves on the bicentennial of living in a country where even a dissident can be a hero, once dead.

Robson’s isolation is reminiscent of the near disappearance of another black icon. Although he was considered an enemy of the white establishment for almost all of his public life and during the first quarter of his death, a new generation of black artists, led by Spike Lee, has reclaimed the Malcolm Half a century after his death, Paul Robeson, the tallest tree in the forest, is still waiting to be reassessed.

-

Excerpted from the book Kings and Pawns by Howard Bryant. Copyright © 2026 by Howard Bryant. From Mariner’s books, published by HarperCollins. Reprinted with permission.

🔥 **What’s your take?**

Share your thoughts in the comments below!

#️⃣ **#Dangerous #Man #America #Paul #Robeson #Hollywood #blacklist #books**

🕒 **Posted on**: 1769026048

🌟 **Want more?** Click here for more info! 🌟