💥 Read this trending post from Culture | The Guardian 📖

📂 **Category**: Theatre,Henry V,Royal Shakespeare Company,Stage,Culture,Kenneth Branagh,Nicholas Hytner,Adrian Lester,Politics

📌 **What You’ll Learn**:

I They have long argued that Shakespeare’s historical plays have more urgent relevance today than his tragedies. The issues they raise – such as the nature of good governance and the difficulty of deposing a tyrant – are precisely the ones that continue to haunt us. Henry V, which will soon be given a new RSC production directed by Tamara Harvey, seems particularly timely as we live in a world where the threat of war is painfully real.

It is also a play that constantly changes its meaning. “There is no better way to find out which way the cultural and political winds are blowing than to go see a performance of Henry V,” James Shapiro wrote in The Guardian in 2008. We were reminded that in 1599, when the play was first performed, theatergoers waited anxiously to find out whether the Irish uprising had been suppressed.

There are two main film versions that have very different focuses. Laurence Olivier’s 1944 film To the Commandos of England was dedicated and considered a major contribution to the war effort. In contrast, Kenneth Branagh’s 1989 film was haunted by the specter of Vietnam and replaced the muddy grays and browns with Olivier’s enhanced colors.

In short, Henry V is a slippery, ambiguous work with the air of a chameleon. Looking at previous productions, I also noticed how they subtly change depending on whether they are played separately or presented as part of a sequence. One of the first versions I saw was at Stratford in 1964, when it was directed by Peter Hall and John Barton, and was part of Shakespeare’s landmark cycle of eight plays: much of the fascination lay in watching Ian Holm’s transition from the cold Prince Hal to the more sympathetic Henry. Even through the mists of time, I remember how this production struck a balance between rhetoric and reality. Eric Porter’s chorus was entirely Elizabethan in character, adding a romantic touch to history. Henry Hulme was a stubborn player who, after Agincourt, joined his rain-soaked troops in pushing a chariot off the stage while wearily singing Te Deum.

Michael Boyd went further in his 2007 production to highlight the play’s contradiction. Geoffrey Streatfield’s Henry was a character of bewildering contradictions: a contemplative recluse who forced himself to become a military leader, and a punitive warrior capable of unexpected tenderness. After graphically threatening the citizens of Harfleur with unspeakable horrors (“spit your naked children on the pikes”), he then turned to his uncle, Exeter, and calmly said “Have mercy on them all.” Even when the King acted like a war criminal under the infamous injunction “Then every soldier whom he takes prisoner shall be put to death,” I felt that Streatfield was driven by the stress of battle to issue a wholly unworkable order.

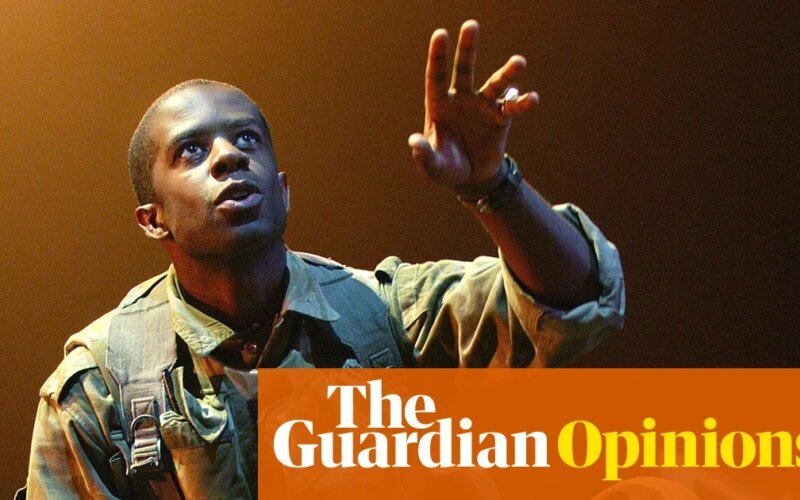

Surveying a mix of individual productions, I was struck by their continuing desire to glamorize war and increase the relevance of modern theatricality. Produced by Adrian Noble in 1984, in which a young Branagh first wrote the role of Henry, I am reminded of the image of working-day English soldiers huddled together in the rain. Ron Daniels’ 1997 version, with Michael Sheen as King, began and ended at the memorial in a powerful reminder of the consequences of war. Edward Hall’s 2000 production, with its references to Dad’s Army and Alo Alo, suggests that patriotism itself was confused, self-contradictory, and circumstantial. Famously, Nicholas Hytner’s 2003 production for the National Theatre, with Adrian Leicester as King, cast shadows from Iraq and was, in Hytner’s own words, the story of “a charismatic young English leader who commits his forces to a dangerous foreign invasion for which he must struggle to find justification in international law.”

So, if Henry V often serves as a barometer of the era, what can we expect from the new Stratford version? Tamara Harvey is the first woman to direct the play for the RSC and will have a company of 11 men and eight women, with Alfred Enoch playing the king. The main question will be how the current events are refracted through the play. We live in a world of chaos, instability and fractured alliances. Burgundian’s climactic rhetoric about the devastating impact of war – where survivors grow like savages – as do soldiers / and do nothing but contemplate the blood – has taken on new force. For the first time in generations, we think about the possibility of world war. However, when you look at existing military conflicts around the world, especially in Ukraine, you see acts of individual and collective bravery. For all these reasons, this might be a good moment to revive this play, rich in contradictions, with its strangely Shakespearean mixture of heroism and irony.

🔥 **What’s your take?**

Share your thoughts in the comments below!

#️⃣ **#Henry #barometer #times #Shakespeares #war #play #global #chaos #stage**

🕒 **Posted on**: 1769044333

🌟 **Want more?** Click here for more info! 🌟