🚀 Discover this awesome post from Culture | The Guardian 📖

📂 Category: John le Carré,Books,University of Oxford,Oxford,Espionage,Exhibitions,Thrillers,Fiction,Culture,UK news

📌 Main takeaway:

Lamp workers, dock artists, babysitters – they have acquired a whole new meaning thanks to John le Carré. As his fans know, they are part of the tradecraft practiced by the spies he wrote about so evocatively. Now, nearly five years after his death, an exhibition called Tradecraft is on display, revealing the techniques and motivations of the characters’ true creator, David Cornwell.

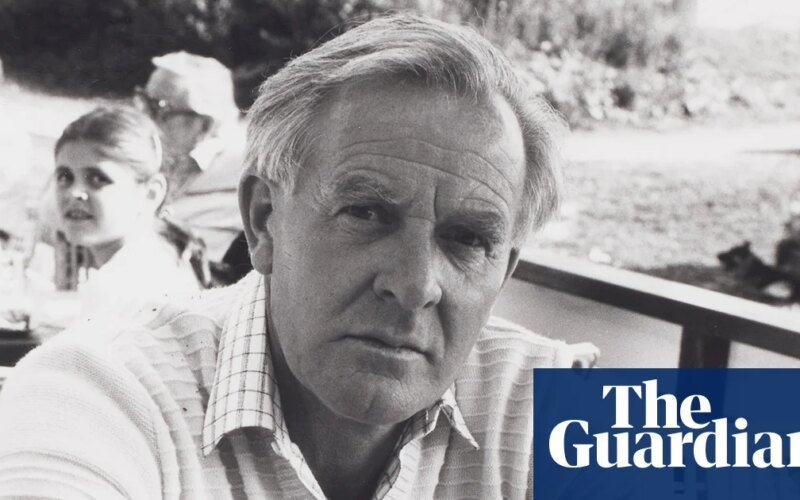

As you enter the exhibition at Oxford University’s Bodleian Library, you are greeted by a large portrait of Cornwell, wearing a black bucket hat, looking straight ahead with piercing eyes, his chin resting gently on his clasped hands. The photo included two of his quotes. One of them says: “I am not a spy who writes novels. I am a writer who worked briefly in the secret world.” The second, after asking who, if anyone, can we trust, continues: “What is loyalty—to ourselves, to whom, and why? Who, if anyone, can we love? And what is the relationship of the individual who provides care to the institutions he serves?”

They’re questions he’s had since he was a child, with a mother who abandoned and lied to him, and Ronnie’s cheating, delusional father who spent time in prison. Among the books included in the exhibition is “The Perfect Spy,” which he described as the most autobiographical of his novels, and in which the central character, Magnus Pym, is obsessed with his father, Rick, a seductive con man.

Betrayal and espionage are of course the dominant themes in his Cold War novels featuring his hero, George Smiley, themes that Cornwell experienced first in reality, then in fiction. After serving National Service in the Army Intelligence Corps, he was offered a place at Lincoln College, Oxford. The exhibit includes cartoons he drew for the college magazine Lincoln Imp. There are articles written for the Oxford Left magazine. His colleagues were among those about whom Cornwell passed information to MI5, one of his first assignments for the agency, and which he later said he regretted.

A handwritten note shows how uncomfortable he was amid early speculation about his espionage. “Why would people want me to have opinions about espionage? If I wrote about love, or cowboys, or even sex, people would consider that this was my interest, and so I wrote stories about it,” he wrote.

His college colleague and university president was Vivian Green with whom Cornwell developed a close relationship (he painted Green for the Imp). Green was Cornwell’s teacher at Sherborne School and oversaw Cornwell’s marriage to his first wife, Anne Sharp. A reference from Green reveals that he described his former student as “congenial, pleasant and loyal.” One of Lincoln’s teachers later recorded: “Mr. Cornwell has written his medieval texts very cleverly,” adding: “He should make more use of his facts.” Unbeknownst to him at the time, Cornwell’s advice was to achieve amazing results.

Although Smiley, portrayed by Alec Guinness in the BBC television series Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy and Smiley’s People, was a composite character, the correspondence between the actor and novelist featured in the show shows how much Cornwell was inspired by Green. “George Smiley must have all the qualities I lacked: Vivien’s patience, his prudence, his good judgement, his memory. And that strange loneliness that comes from knowing and seeing so much about which you can do so little,” Cornwell once wrote, as le Carré wrote.

Fact and fiction seem to merge when the younger Smiley is described at Oxford as “inferior” but “much thinner”. In a letter to Cornwell, Guinness wondered whether he was suitable for the role of Smiley. “Although I have a thick body, I am not round or with a double chin,” he wrote.

The exhibition includes what he called “observation.” “From the first book,” Cornwell wrote, “my main characters have been forced to ask themselves what they owe to Caesar, and what they owe to their own consciences.” After the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War, Cornwell turned his attention to contemporary issues on his conscience.

The exhibition shows how much Cornwell, like a journalist, relied on sources – including his former MI6 colleagues – and how he traveled extensively to research his conspiracies. He has consulted extensively on the arms trade for The Night Manager, and the pharmaceutical industry for The Constant Gardener. He accused the industry – now the subject of much controversy – of “obsessive secrecy at all levels”. He pointed out: “Pharma has spoken… Be grateful for our amazing successes, pay whatever we say to you, and be silent.”

While crafting the song Mission, about a Western coup plot in eastern Congo, Cornwell described “Corporate Responsibility” as “another heart of darkness.” The main character of “The Most Wanted Man” was based on the true story of Murat Kurnaz, a Turk who grew up in Germany and was extradited to Guantanamo Bay. Cornwell spoke to the manager of the Bellevue Palace Hotel in Bern, Switzerland, to ask if he could name the establishment in the money laundering and mafia conspiracy “our kind of traitor.” He met former Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat while writing The Little Drummer Girl, a plot with striking contemporary resonances.

Some former ministers and intelligence chiefs expressed regret, and some concern, about what they criticized as the satirical tone and negative message in Cornwell’s novels. Others welcomed the discussions it sparked. Cornwell recalled several years ago how he had been invited by MI5 to lecture their officers. He was welcomed but told them it was unlikely he would be accepted if he applied to join the agency again.

-

The Tradecraft exhibition, curated by Federico Varese and Jessica Douthwaite, runs at Weston Library, in the Bodleian, Oxford, until 6 April.

🔥 Share your opinion below!

#️⃣ #Story #Spy #Stories #Show #Reveals #Secrets #John #Carrés #Craft #John #Carré