✨ Check out this trending post from Culture | The Guardian 📖

📂 Category: Hip-hop,Rap,Music,Culture,Nigeria

📌 Key idea:

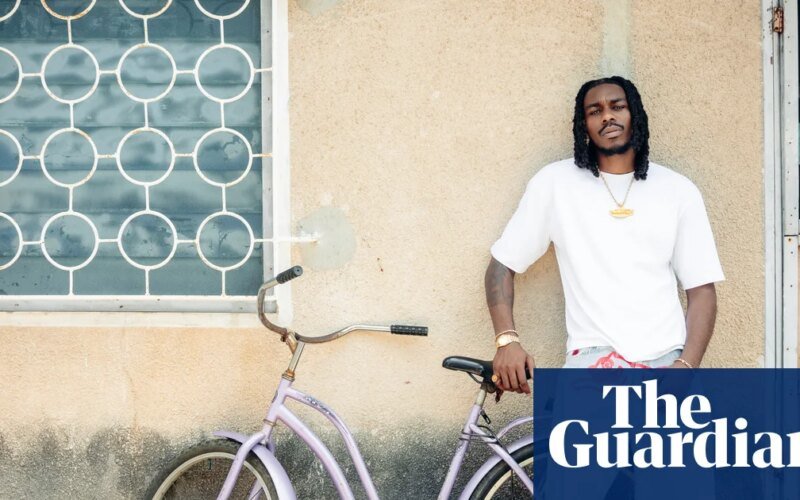

WWhen Knox was 12 years old, his parents made a crucial decision. The budding rapper was having problems at his school in London, so, in an attempt to rectify that, they sent him to a boarding school in Enugu, Nigeria. “Some people didn’t get me,” Knox says as we talk in his record label’s office. “Like people say in Britain: ‘Go home.’ But people in Nigeria were saying: “You don’t belong here either.”

Boarding school proved to be a difficult two years for Knox, whose real name is Afamefuna Ashley Nwachukwu. He soon picked up a handful of “enemies”, including the most popular boy of the year, who threatened him on his first day and warned him to stay away from his girlfriend. Miles away from the place he called home, and without amenities like a washing machine, Nax found solace in his friendship with the school cook. “She was a mom figure,” he says. “If I’m sad or homesick, I’ll go there.”

Knox’s tales of his two years in Nigeria feed into his new album, A Fine African Man, which finds the 30-year-old contemplating “where I stand in the world, what kind of person I am, and how my values are affected by things that happened at that time.” On “Cut Knuckles,” he contrasts the luxuries of his current life (“Now I watch the brand-new things I got to dry in the dryer”) with memories of having to wash his clothes by hand in Enugu (“No washing machine / The man wasn’t a teenager / But he used to wash my clothes by hand / Cut knuckles, smell of water”).

Nax has spent the last decade taking his conscious, narrative-driven lyricism to the top of British rap. When his breakthrough single, 21 Candles, was released on SoundCloud in 2015, his musings on the impermanence of friendships marked him as someone relatable and introspective, even vulnerable. You can hear those qualities again on new track “Are You Okay?”, which contemplates the limits of fame and money; and on The Three Musketeers from his 2022 debut album Alpha Place, which revolves around his experience of survivor’s guilt, which he reflects on for being the only one of his three best friends to escape the fights and daily tensions of his Kilburn residential home. Alpha Place racked up millions of streams and took home the Mobo Award for Album of the Year, in a joint win with Little Simz (Sometimes I Can Be an Introvert).

Nax told me that it was during the summer before high school that he first started making music with friends from his estate. When he got to high school there was a recording studio, so “during our lunch break, me and seven of my friends went and recorded eight tapes after eight tapes.” Soot was a schoolyard obsession before he was sent to Nigeria, but when he returned in 2008, “the temperature had changed.” The rap was on: “Everyone was talking about Giggs. Talkin’ da Hardest just came out.”

Nas was using soul samples and “high-pitched female vocals”, rather than grime electronic production, and while he absorbed the classic albums of Nas and MF Doom, his move towards hip-hop continued. Nas’s Illmatic was particularly foundational in shaping his own music, even inspiring the name of the Knucks’ first mixtape, Killmatic. “The brutality, the lyricism, the stories, how hungry Nas was: I saw a lot of that in myself.”

It wasn’t just the music scene that changed when Knox returned from Nigeria. In north-west London, he was surrounded by diverse communities, but by the time he returned to the UK, his family had moved to Watford in Hertfordshire, where he attended a “very white” school. Before this, Knox was known as Afamifuna or Afam. Now he feels insulted whenever his name is mentioned in councils. When the school principal suggested he use his middle name, Ashley, he was “quick to accept it.”

Does he regret dropping his Nigerian name? Yes and no. He says it was a coping strategy. Plus everyone calls him Knucks now anyway (short for his nickname “Knuckles”, which came from a playground game and his favorite character Sonic). However, he also feels a bit self-conscious about it, he says, something he documents on his new song, My Name Is My Name, and on the album in general. (The beautiful African man is, after all, an afam.)

Nax has traversed drill, soul, jazz and burgeoning classical hip-hop over the course of his career – and now he’s tapping into West African rhythms. Nigerian influences run throughout the album. When he visited in 2023, he stood at the bus stop next to his old boarding school and recorded the conductors, eventually incorporating these field recordings into the tracks. In a masquerade ball, the ogyen, a cowbell-like instrument used during masquerade parties in Igboland, and the oja flute are used, which you may recognize from the song Amapiano by Nigerian singer Ksi that became a hit in Ojabiano. “I’m making an effort to put these tools out there so people from back home can relate to them on a deeper level,” Nax says.

With his parents being strict enough to send him to boarding school in Nigeria, I wonder how they responded to his rap aspirations. Nax says they were excited about the idea, but also insisted on going to university. (He graduated from UC Rochester with a degree in Animation and Computer Graphics.) They also had confidence in his manager and mentor, Nathan “NRG” Rodney. Before his death in a car accident in 2018, Rodney became one of the big influences in Knox’s life, helping him course-correct whenever selfish or selfish instincts took him in wayward directions. Nax’s voice trembles when talking about NRG’s death: “It put me in a catatonic state, because I was madly in love with him. He was like a big brother.”

You can feel Rodney’s guidance in the blossoming maturity of a beautiful African man. Four years ago, when Nax’s father was transferring money to friends and relatives in Nigeria, he asked the rapper if he could add some money for someone else he considered family: the cook he was taking care of at boarding school. She was bedridden and unable to work, and when the money arrived, she was apparently moved to find that she had made such an impression on Nax. Her story is retold in the album’s song Yam Porridge, which includes intimate memories of her late father.

“I made an effort to tell the story from her point of view, and leave myself out until the end,” Nax says.

A Fine African Man is released on October 31 on NoDaysOff

🔥 Share your opinion below!

#️⃣ #didnt #belong #Rap #star #Nax #talks #uprooted #childhood #bus #conductors #sign #hip #hop