🔥 Check out this must-read post from Hacker News 📖

📂 Category:

✅ Main takeaway:

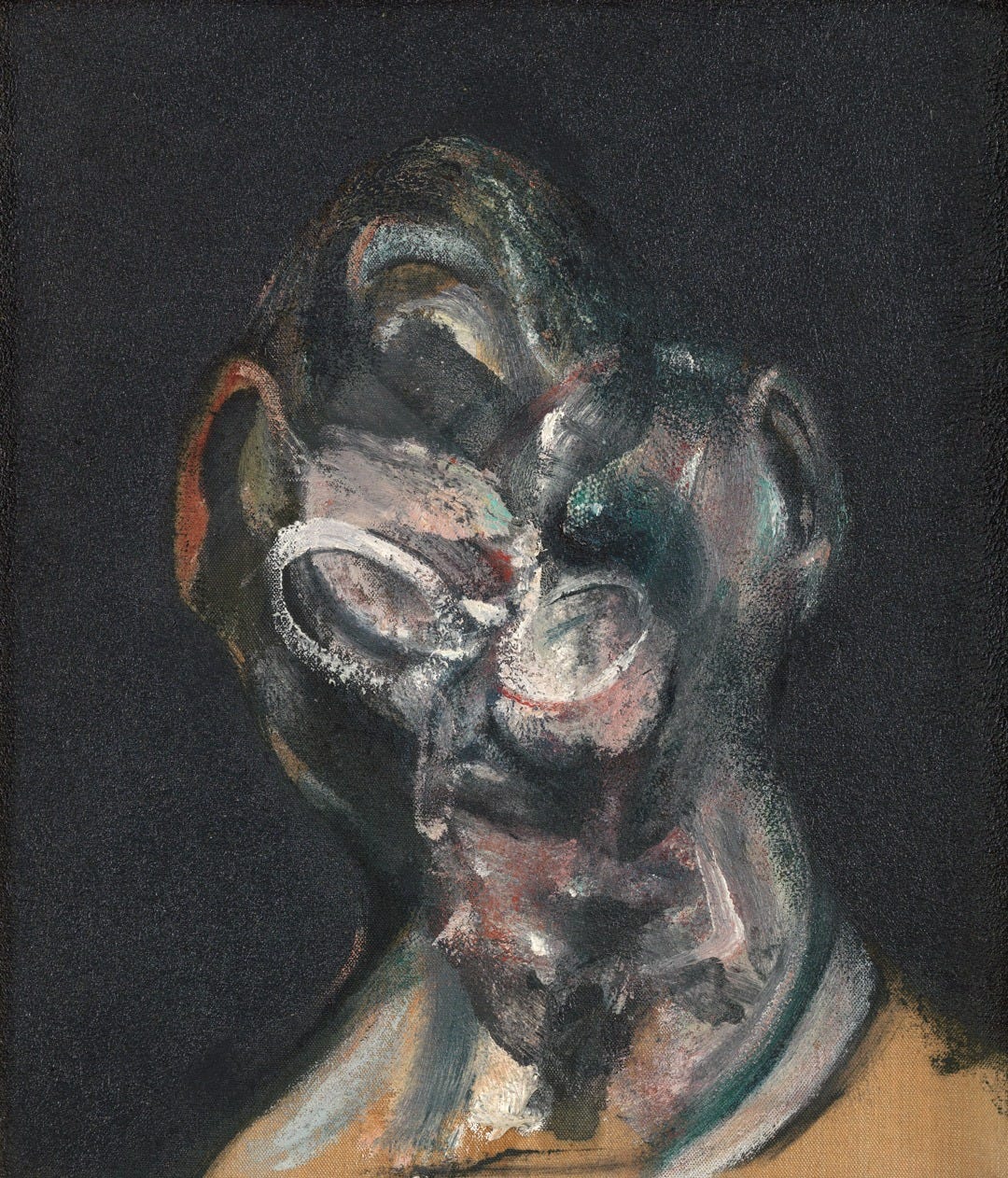

Portrait of a Man with Glasses I, Francis Bacon, 1963

This essay can be read as a complement to last year’s “How to think in writing.”

Thoughts die the moment they are embodied in words.

—Schopenhauer

In the 1940s, when the French mathematician Jacques Hadamard asked good mathematicians how they came up with solutions to hard problems, they nearly universally answered that they didn’t think in words; neither did they think in images or equations. Rather, what passed through the mathematicians as they struggled with problems were such things as vibrations in their hands, nonsense words in their ears, or blurry shapes in their heads.

Hadamard, who had the same types of experiences, wrote in The Psychology of Invention in the Mathematical Field that this mode of thinking was distinct from daydreaming, and that most people, though they often think wordlessly, have never experienced the kind of processing that the mathematicians did.

When I read this, in December 2024, all sorts of questions arose in me. First of all, what does it even mean? Do they not think in words and equations at all? And secondly, how do I square this with my personal experience, which is that whenever I write what I think about a subject, it always turns out that my thoughts do not hold up on paper? No matter how confident I am in my thoughts, they reveal themselves on the page as little but logical holes, contradictions, and non sequiturs.

I recognize myself when Paul Graham writes:

The reason I’ve spent so long establishing [that writing helps you refine your thinking] is that it leads to another [point] that many people will find shocking. If writing down your ideas always makes them more precise and more complete, then no one who hasn’t written about a topic has fully formed ideas about it. And someone who never writes has no fully formed ideas about anything nontrivial.

How come Hadamard’s colleagues are able to have productive thoughts, working in their heads, without words, sometimes, for days on end?

Hadamard’s book is most famous for its detailed discussion of what Henri Poincaré called the “sudden illumination”—the moment when the solution to a problem emerges “in the shower” unexpectedly after a long period of unconscious incubation.

The hypothesis here is that if you work hard on a problem, you soak your subconscious with it. Wrestling with a problem helps you build a mental model of what you know and what you don’t—providing the subconscious with building blocks to work with. (You can’t have genuine intuition and inspiration in areas where you lack knowledge.) Then, once you drop the problem from conscious thought and go take care of the dishes or something, the subconscious begins a silent and parallelized search, trying many, many alternatives (in a somewhat random fashion), until something snaps in place. When this happens, the solution bubbles back up to the conscious mind, as if out of nowhere, making you freeze mid-motion with a stack of dirty plates in your hands.

This is a very useful thing to know about the mind, because it means you can steer your subconscious towards the particular problems you want it to work on. By priming yourself with important problems before doing the dishes or going for walks or sleeping, you make sure your mental resources are used on what matters for you, instead of, for example, the open loops in a Netflix series you watched before bed. It is free labor.

But—this is not what Hadamard is talking about when he describes the wordless thought of the mathematicians and researchers he has surveyed. Instead, what they seem to be doing is something similar to this subconscious, parallelized search, except they do it in a “tensely” focused way.

The impression I get is that Hadamard loads a question into his mind (either in a non-verbal way, or by reading a mathematical problem that has been written by himself or someone else), and then he holds the problem effortfully centered in his mind. Effortfully, but wordlessly, and without clear visualizations. Describing the mental image that filled his mind while working on a problem concerning infinite series for his thesis, Hadamard writes that his mind was occupied by an image of a ribbon which was thicker in certain places (corresponding to possibly important terms). He also saw something that looked like equations, but as if seen from a distance, without glasses on: he was unable to make out what they said.

I’m not sure what is going on here. But here’s a speculation. As I understand it, when one part of our brain is working, it often inhibits another—if you put words to distressing feelings, for example, the language-oriented parts of your brain inhibit the amygdala, which reduces the emotional distress. Similarly, when you are focused on a task at hand, the executive control network of your brain will tend to inhibit the default mode network which is responsible for mind wandering. (This might explain why illuminations tend to occur mainly in the shower, when the executive control networks downregulate and the mind is allowed to wander.)

Here’s my speculation: perhaps Hadamard and the other great mathematicians are able to enter into a modality of thought where they are able to keep both the default mode network and the executive control network on at the same time. Perhaps this allows them to do a sort of subconscious, in-the-shower-type processing, while still maintaining enough conscious focus to ensure the thoughts don’t drift away from the problem and its constraints.

When I look into this, I notice that there is research indicating that when doing certain types of creative work, the default mode network and the executive control network are, indeed, active at the same time, which they usually aren’t. Individuals who are experienced in a creative field seem to have the capacity to keep the default mode network turned on, allowing them to generate many permutations of ideas, while steering it with the executive control network, ensuring their parallelized mindwandering is constrained by the facts of the problem. I suspect we are all capable of this to some extent, but doing it to the extent Hadamard’s subjects did is akin to a ballerina spinning on her toes: a mental posture that requires serious practice to develop the necessary muscles and coordination.

I’m not well-versed in neuroscience enough to know if I’m interpreting this right; I’m just speculating.

But what we do know is that Hadamard, as he worked, would pace up and down his room with what “witnesses to [his] daily life and work” called his “inside” look. (Others, like Poincaré and Helmholtz, seem to have sat at their desks, staring into nowhere.) And this type of deep, consciously-blurry concentration could go on for a long time: Hadamard mentions that he only stopped walking if he needed to write down a proof (reluctantly). An acquaintance writes that a friend of his shared an office with one of the best now living physicists; this physicist’s work habit was to come into the office in the morning and then stare into the wall for 8 hours before going home. Imagine holding a productive thought for that long without writing any steps down and, presumably, without even compressing things into words inside your head!

Hadamard writes that he sometimes used algebraic signs when dealing with easy calculations, but adds that, “whenever the matter looks more difficult, they become too heavy a baggage for me.”

Why are words too heavy?

Reasoning from my experience, I suspect it is because words are laborious. When we put words to a thought, we have to compress something that is like a web in our mind, filled with connections and associations going in all directions, turning that web into a sequential string of words; we have to compress what is high-dimensional into something low-dimensional. This has all sorts of advantages, which I will return to, but the point I want to emphasize here is that compression is effortful. It takes intense concentration to find the right words (rather than the sloppy ones that first come to mind), and then to put them in the proper order. As James Joyce said to his friend when he was asked why he looked so gloomy, “I’ve only written seven words today…” “But why then are you in despair—seven words is a lot for you!” “I don’t know in which order to put them…”

If we can avoid the compression step, and do the manipulations directly in the high-dimensional, non-linguistic, conceptual space, we can move much faster.

But this is a big if. Most people, myself included, have too weak mental models to do this kind of processing for complex problems, and so, our thoughts are riddled with contradictions and holes that we often don’t notice unless we try to write them down. We can move faster in wordless thought, but we’re moving at random. If, however, you have deep expertise in an area, like the mathematicians, it is possible to let go of the language compression and do a much faster search. M, who started his career as a physicist, tells me that when he was 13 and read that Einstein thought without words, he felt disappointed since his mind didn’t work like that; then, “a decade and many thousands of hours of mathematics and physics later,” he reread the passage and recognized himself almost completely. I guess this was because the labor of learning mathematics, done largely through reading and writing his way through complex ideas and problems, had given him deep enough mental models to make words somewhat superfluous.

But even then, as Hadamard notes, writing is a necessary step of the process. The insights arrived at wordlessly need to be submitted to the rigor of mathematical notation and logic, to test their validity. It is a sort of feedback mechanism: unless the intuition holds up on the page, it is a false intuition.

The written results also work as relay results. By writing something down and making sure it is solid, we can offload that thought from working memory and instead use it as a building block for the next step of the thought. Or, to use a metaphor by the mathematician William Hamilton, deep thinking is like building a tunnel through a sandbank:

In this operation, it is impossible to succeed unless every foot, nay, almost every inch in our progress be secured by an arch of masonry before we attempt the excavation of another. Now, language is to the mind precisely what the arch is to the tunnel. The power of thinking and the power of excavation are not dependent on the words in the one case, on the mason-work in the other; but without these subsidiaries, neither process could be carried on beyond its rudimentary commencement.

So writing—and reading, seriously, the writings of others—is a way to collect stepping stones: ideas that have been stabilized enough that they can carry us as we walk deeper into the thought space.

But this stabilization of meaning can go wrong, too, if we stabilize ideas that aren’t ready to be stabilized yet. When writing, there are all sorts of details that need to be specified for our paragraphs to make sense, and if we don’t know what should go into a sentence, it is all too easy to fill in the uncertain parts with guesses. At least my brain has the most miraculous autocomplete function and supplies me with credible endings to any sentence I start—often credible nonsense. But when the nonsense is there on the page, next to thoughts I’ve settled through hard work, it looks respectable! It often takes considerable work to realize I’ve fooled myself.

This was another reason Hadamard’s subjects gave for why they were reluctant to use words: they were afraid of the false precision writing forces onto thinking. They were afraid of premature precision and the confusion it breeds. By thinking in blurry images, or tensions of the hands, or sounds, they could keep their thoughts accurately vague in the areas where there was still uncertainty. They wrote down on paper, as settled, only mostly what was actually known. If you are disciplined, you can write in such a way that you avoid false precision.

To sum up: the relationship between verbal thinking and deep wordless concentration is complex.

-

Non-verbal, blurry thinking is faster and can search in a broader way, but it is more error-prone than verbal thought.

-

Good writing tends to come from an attempt to capture in words something you understand wordlessly, rather than moving ideas around on the page; but, paradoxically, a generative subconscious is usually one that has been trained by writing and deep reading, which provides the subconscious with relay results and other mental structures necessary for deep thought.

-

Writing forces precision, which can fool us into locking in details we have no reason to lock in, but written notes (or drawings) are a necessary aid when thinking long chains of thoughts.

Over the last nine months, as I’ve been thinking about this topic, I’ve become more mindful about when words hinder and when they help. I notice that I spend more time in wordless thoughts than I used to. But I’m also more deliberate about using writing to structure my brain so it feeds me better thoughts.

As always, a big thank you to the paying subscribers who fund the work on the public essays. I couldn’t do this without you! I also want to thank Johanna Karlsson and Michael Nielsen for discussion about the topic. Esha Rana helped me with the final edit.

How to think in writing

The reason I’ve spent so long establishing this rather obvious point [that writing helps you refine your thinking] is that it leads to another that many people will find shocking. If writing down your ideas always makes them more precise and more complete, then no one who hasn’t written about a topic has fully formed ideas about it. And someone who neve…

Tell us your thoughts in comments! Tell us your thoughts in comments!

#️⃣ #words

🕒 Posted on 1761278584