✨ Read this trending post from Hacker News 📖

📂 **Category**:

💡 **What You’ll Learn**:

Two days ago, someone named Matt Shumer posted an essay on Twitter with the title “Something Big Is Happening.” Almost immediately, his essay went extremely viral. As of this writing, it’s been viewed about 100 million times and counting; and it’s been shared by such strikingly diverse figures as the conservative commentator Matt Walsh (“this is a really good article”) and the liberal pundit Mehdi Hasan (“perhaps the most important piece you read today, this week, this month”). I’ve heard countless reports of people being sent the article unprompted by parents and siblings and friends. I expect that Shumer’s essay will end up being the most widely-read piece of long-form writing this year.

And it’s not hard to see why it’s touched such a nerve. For most people who use it, “artificial intelligence” amounts to free-tier ChatGPT; for them AI is useful for answering questions and drafting emails. But now people are starting to realize that AI will be a massive force in the world. This is the year that ordinary people start to think about how it’ll change human life. And it shouldn’t shock you that the first thing they’re thinking about is whether AI will take away their jobs, render any skills they have worthless, and make their lives worse. There’s a growing sense of panic. The Atlantic is talking about AI job loss. Bernie Sanders is talking about AI job loss. Matt Walsh says that “AI is going to wipe out millions of jobs. It’s happening now. Everything is changing. The avalanche is already here. Most of what we’re currently arguing about will be irrelevant very soon.” We are entering a moment of panic.

So it’s the exact perfect moment for someone claiming to be part of “the AI industry” to write an essay saying that we’re in a moment just like February 2020, watching COVID infections go exponential. And just like COVID did, artificial intelligence is about to crash into ordinary people’s lives with unbelievable force; and that the only way they can get ahead of this massive shock is by buying subscriptions to AI products, saving more money, spending an hour a day experimenting with AI, and perhaps following Matt Shumer so that you can “stay current on which model is best at any given time.” It’s not a very good essay—much of it was transparently generated by AI, and Shumer admits as much—but timing and positioning are much more important factors for the success of any argument. And Shumer’s timing and positioning were impeccable. I don’t think that any other piece of writing is going to do more to shape what ordinary people think of AI than Shumer’s essay will. It’s going to become a key document of this moment.

And that’s a very bad thing. Not because the essay is AI-generated, but because it’s entirely wrong on the merits of what AI will do. I don’t think that we’re living in anything like the pre-COVID moment of February 2020. I don’t think that ordinary people have very much to worry about from AI. And I don’t think that the forecasts that people are taking away from the essay—imminent mass job loss, the entire world transforming rapidly starting in the next few months, “the avalanche is already here”—are grounded in reality. And I’m worried that these misperceptions are going to result in disaster.

I’m not saying this because I don’t believe in AI. I think that AI is going to be extremely important; I expect that it will end up being at least as important as the discovery of electricity or the steam engine, and there’s a good chance it’s the most important thing that humans ever invent. I think that the future is going to be very different from the past.

But I don’t think that this implies the “February 2020” world that people seem to imagine. I honestly don’t think that we’re going to see mass unemployment, or the sudden death of human cognitive labor, or anything that feels like an “avalanche.” The years to come will be weird, especially if you’re keeping abreast of the latest developments in AI. But the actual impacts of AI in the real world will be a lot slower and more uneven than people like Shumer seem to think. Human labor is not going away anytime soon. And whether or not they spend an hour a day using AI tools, ordinary people will be fine.

AI will be extraordinarily capable: it will continue to awe and amaze us with what it can do, and it will only get better, and it will get better at an accelerating pace. There are already a lot of tasks where AI is as capable as a competent human; and that number is only going to grow.

But that doesn’t actually imply the mass replacement of human labor.

The most important thing to know about labor substitution, the place where any serious analysis has to start, is this: labor substitution is about comparative advantage, not absolute advantage. The question isn’t whether AI can do specific tasks that humans do. It’s whether the aggregate output of humans working with AI is inferior to what AI can produce alone: in other words, whether there is any way that the addition of a human to the production process can increase or improve the output of that process. That’s a very different question. AI can have an absolute advantage in every single task, but it would still make economic sense to combine AI with humans if the aggregate output is greater: that is to say, if humans have a comparative advantage in any step of the production process.

It’s certainly the case right now, even in a domain like software engineering where the extent of AI capabilities is on full display, that the human-AI combination, the “cyborg,” is superior to AI alone—not least because you still need to tell the coding agent your preferences, or your company’s preferences, or your customer’s preferences. This is good for human labor, because it means that workers are more productive, and as long as demand for the goods they produce is elastic, we should be pretty optimistic about human labor under this regime. (This is probably why the number of job postings for software engineers has increased in the twelve months since Claude Code was first released.)

The faster that AI capabilities advance, of course, the quicker we’ll tend to see complementarity diminish: I don’t think that the cyborg era is necessarily a permanent one. The world where human complementarity disappears entirely isn’t a realistic one: it’s a corner solution where AI is so superior at every conceivable task, under every conceivable condition, that there is literally nothing a human could do to improve any production process anywhere. That’s not a realistic scenario. It’s not hard to imagine that we move closer to such a world in an asymptotic way, approaching but never reaching. But serious human complementarity with AI will last much longer than people today seem to think.

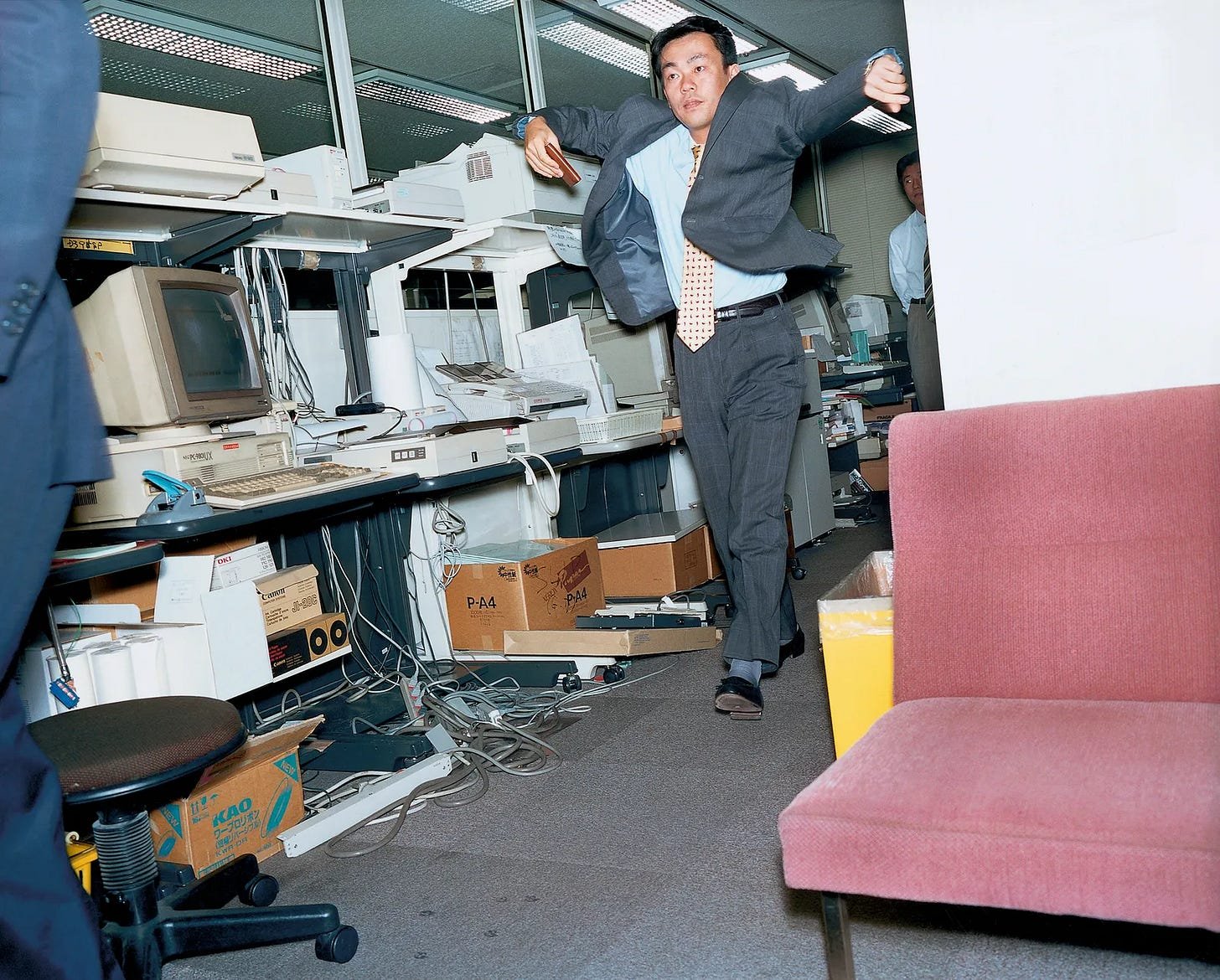

I don’t say that because I think that AI models are bad or because I think they won’t get better; I think that AI models are very good and will get much better. No. The fault is not with the models, but with us. The world is run by humans, and because it’s run by humans—entities that are smelly, oily, irritable, stubborn, competitive, easily frightened, and above all else inefficient—it is a world of bottlenecks. And as long as we have human bottlenecks, we’ll need humans to deal with them: we will have, in other words, complementarity.

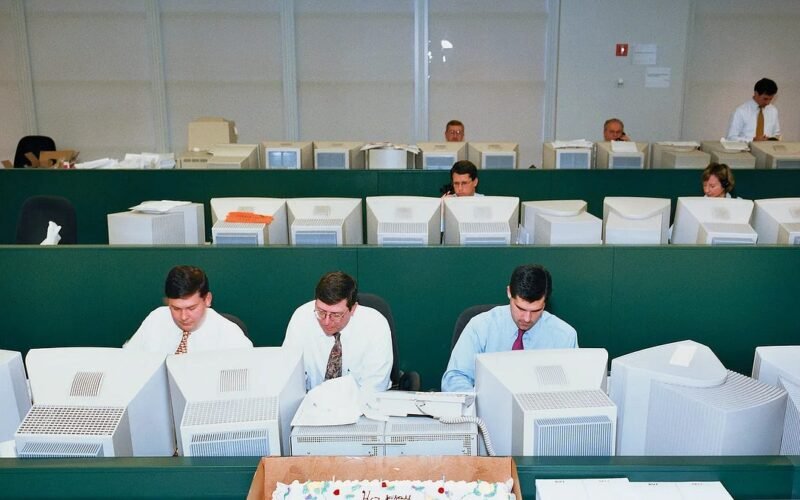

People frequently underrate how inefficient things are in practically any domain, and how frequently these inefficiencies are reducible to bottlenecks caused simply by humans being human. Laws and regulations are obvious bottlenecks. But so are company cultures, and tacit local knowledge, and personal rivalries, and professional norms, and office politics, and national politics, and ossified hierarchies, and bureaucratic rigidities, and the human preference to be with other humans, and the human preference to be with particular humans over others, and the human love of narrative and branding, and the fickle nature of human preferences and tastes, and the severely limited nature of human comprehension. And the biggest bottleneck is simply the human resistance to change: the fact that people don’t like shifting what they’re doing. All of these are immensely powerful. Production processes are governed by their least efficient inputs: the more efficient the most efficient inputs, the more important the least efficient inputs.

In the long run, we should expect the power of technology to overcome these bottlenecks, in the same way that a river erodes a stone over many years and decades—just as how in the early decades of the twentieth century, the sheer power of what electricity could accomplish gradually overcame the bottlenecks of antiquated factory infrastructure, outdated workflows, and the conservatism of hidebound plant managers. This process, however, takes time: it took decades for electricity, among the most powerful of all general-purpose technologies, to start impacting productivity growth. AI will probably be much faster than that, not least because it can be agentic in a way that electricity cannot. But these bottlenecks are real and important and are obvious if you look at any part of the real world. And as long as those bottlenecks exist, no matter the level of AI capabilities, we should expect a real and powerful complementarity between human labor and AI, simply because the “human plus AI” combination will be more productive than AI alone.

And I suspect that the presence of bottlenecks explains one of the big questions of the last few years, which is why, given how good the models are, we’ve seen such a small amount of actual labor replacement.

If you had come to me ten years ago and told me about the leading AI models that we have today, that GPT 5.2 and Claude Opus 4.6 would be publicly available via a cheap API call, I would have thought that we’d be seeing something like mass unemployment. I would have said something similar, honestly, about GPT-4: if you had shown GPT-4 to me ten years ago, I would have thought that within 12 or 24 months of its release, we’d at least have automated away most of the outsourced customer service industry. People were saying the same about GPT-3 when it came out in 2020.

GPT-3 has been out for six years; GPT-4 for three; and none of that has happened. Even in the outsourced customer service sector, the lowest-hanging fruit on the automation tree, we’re just not yet seeing mass layoffs due to AI. I’ll be frank in telling you that this has been a huge surprise to me. (And to others.) There is change, but it is gradual; it looks more like standard technological diffusion than a tsunami of replacement. And we should think seriously about why this has been the case.

Is this because the models aren’t smart enough? I don’t think that’s it. I think the models we have today are very capable, and they’ve been capable for a long time, and they’ll only get more capable from here: we shouldn’t forget how amazing even, say, GPT-3.5 would be from the perspective of 2016. The experience of the last few years should tell us clearly: intelligence is not the limiting factor here. It might be that at the limit, everything is soluble in intelligence; if we invent a digital god, it should presumably be able to figure out how to run a call center. But short of that corner-solution world, we’re still in a regime governed by human bottlenecks. In the case of the call center those might be contractual obligations, or liability issues, or integration with legacy systems, or the human desire to yell at another human when frustrated. But even for this simplest of real-world jobs, we are in the world of bottlenecks.

And as long as we are in the bottleneck world, we should be quite optimistic about human labor.

Why should we be optimistic about human labor at a time when AI is gaining an absolute advantage in a huge set of tasks?

Simply put, because demand for most of the things that humans produce is much more elastic than we recognize today; and as long as humans are complementary to the production process, it won’t be rare for efficiency gains to get swallowed up by demand growth. This is the famous Jevons paradox, the tendency for the more efficient use of a resource to increase total consumption of that resource, rather than decrease it. Energy is the classic Jevons case: we find over and over again that as energy becomes more efficient to produce, people respond not by consuming the same amount of it, but by increasing their consumption—such that overall energy use tends to rise. (Thus the “paradox” part: energy efficiency increases energy consumption!)

And I suspect that the same elasticity of demand that we see with energy applies to a lot of the things that humans create. As a society, we consume all sorts of things—not just energy but also written and audiovisual content, legal services, “business services” writ large—in quantities that would astound people living a few decades ago, to say nothing of a few centuries ago. Demand tends to be much, much more elastic than we think.

Take software. Software simply means “the things that a computer can do”: and because software is so broad and so capable, we should expect that it’s energy-like and that there’s an enormous latent demand for more software in the world. For that reason we’ve found that every increase in the efficiency of software programming—the move from lower-level to higher-level languages, the emergence of frameworks and libraries, the endless move away from bare metal as compute becomes ever-cheaper and more abundant—has resulted in a dramatic increase in demand for software engineering labor. There are many more people employed in software engineering today than there were 20 or 30 years ago. If AI accelerates these productivity gains dramatically, it would not be so outlandish to see demand for software engineering labor rise. We see a version of this, for example, with the huge popularity of Claude Code and Codex. Coding is far more efficient than it used to be; but people have responded by spending much more time coding than they used to, because the latent demand for software is so enormous.

All of this makes me suspect that, as long as we are in the cyborg era of human-AI complementarity, we should be quite optimistic about human labor. The world is governed by bottlenecks; as long as those bottlenecks are real, there will be complementarity between humans and AI; and if the human-AI combination can make human labor vastly more productive, we should expect that to be a very good thing: for consumers of course, who will benefit from an enormous consumer surplus, but also for workers.

So in the short to medium term, complementarity will preserve a place for human labor. But bottlenecks weaken over time and eventually are overcome: human complementarity to AI will always be a wasting asset, and at the limit it’ll converge on zero. Eventually we really will live in an unrecognizable future. What happens then?

I don’t think that it’s worth worrying much about this world. The transition to it will be longer and gentler than people today think; and by the time we reach that state, we’ll have spent quite a while in a world of such abundance and plenty that jobs might simply be superfluous. Perhaps we’ll spend our lives in leisure, pursuing poetry or pure mathematics or the fine art of looksmaxxing. Or maybe this means that we’ll have invented a digital god whose power, wisdom, and intelligence is to ours as ours is to an insect’s: we’ll have immanentized the eschaton. If you believe that this will happen, there’s no point worrying about the displacement of software engineers: you should just try to forget it all and enjoy life while you can, because apocalypse and revelation are on their way.

I suspect that short of that apocalyptic scenario, human labor will always have a place in the world. We’ll invent jobs because we can, and those jobs will sit somewhere between leisure and work. Indeed this is the entire story of human life since the first agrarian surplus. For the entire period where we have been finding more productive ways to produce things, we have been using the surplus we generate to do things that are further and further removed from the necessities of survival. Today, our surplus is large enough that we can pay large numbers of people to be baristas, yoga instructors, physical trainers, video directors, podcast producers, and livestreamers; and we should expect that as the surplus grows, people will find strange and interesting things to do with their lives.

So I have a much more benign view of what AI will do to human labor. I don’t mean to say that every job or every person will be “safe.” There will be people who lose their jobs because of AI; there will be people who find that their skills are no longer valuable because of AI, and there will be people who don’t lose their jobs but who have to make serious adjustments they dislike.

But on the whole the economic transition that AI is ushering in will be much gentler than people seem to think. COVID is a terrible analogy for what’s coming. The ordinary person, the person who works at a regular job and doesn’t know what Anthropic is and invests a certain amount of money in a diversified index fund at the end of each month: that person will most likely be fine. I don’t think they have much to worry about from AI. A lot of things will get better for them, though often in ways that are so gradual and subtle that they’ll hardly notice. A few things will get worse, typically in ways that they will notice. And a surprising number of things won’t change. They’ll have to make adjustments to how they work: some of those adjustments will be pleasant and some will be less so. But those adjustments will happen as they come. They don’t really need to worry.

I do think that there will be a lot of weirdness and instability in the coming years: but that weirdness and instability won’t come from the technology’s actual economic impacts. It’ll more likely come from the political and social backlash that people like Shumer are inciting, intentionally or not. Telling ordinary people that we’re in February 2020 and that there’s an avalanche on the way is incorrect on the merits: but it’s also, frankly speaking, a catastrophic mistake.

I’ve seen how ordinary, non-online people are reacting to Shumer’s essay; and I now recognize, from the ambient sense of fear and panic, that we are in the very early stages of a massive populist backlash to AI. Telling people that AI is probably going to take their job doesn’t end with them getting a $20 subscription to ChatGPT Plus in order to learn about the frontier of technical development. It ends with an enormous cross-party populist movement to stop AI at all costs: with the complete banning of data center construction, with jobs guaranteed for life, and with laws passed to choke off the development and deployment of anything that could potentially make the economy more efficient. And if you think that AI can do very good things for the world, whether this means higher productivity growth or accelerated medical and scientific progress or the discovery of new and more glorious stages of human civilization, then you should recognize that outcome as a catastrophe for human welfare.

Maybe it’s a good thing that someone wrote an essay that broke through to ordinary people and alerted them that AI capabilities are very good and are getting better at a rapid clip. It’s good for people to know that AI can do more than write their emails. And Shumer is right that something big is happening in the world. But we don’t need to terrify ordinary people about what this will mean for them. I think they’ll be fine.

{💬|⚡|🔥} **What’s your take?**

Share your thoughts in the comments below!

#️⃣ **#worried #job #loss**

🕒 **Posted on**: 1771011993

🌟 **Want more?** Click here for more info! 🌟